Strange solar system object is part-asteroid, part-comet

2005 QN173 isn't just any old asteroid.

Scientists have identified a rare solar system object with traits of both an asteroid and a comet.

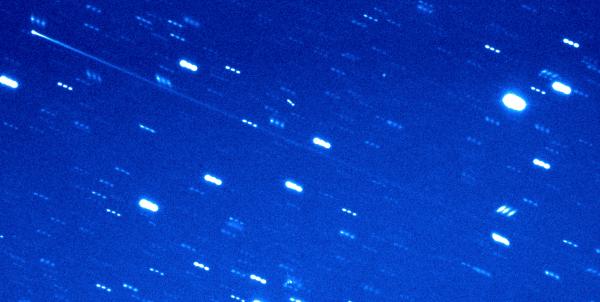

The object, dubbed 2005 QN173, orbits like any other asteroid, but most such objects are rocks that don't change much as they loop through the solar system. Not so for 2005 QN173, which was first spotted in 2005 (hence the name), according to new research. Instead, it looks like a comet, shedding dust as it travels and sporting a long, thin tail, which suggests that it's covered with icy material vaporizing away into space — even though comets usually follow elliptical paths that regularly approach and retreat from the sun.

"It fits the physical definitions of a comet, in that it is likely icy and is ejecting dust into space, even though it also has the orbit of an asteroid," Henry Hsieh, lead author of the new research and a planetary scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, said in a statement. "This duality and blurring of the boundary between what were previously thought to be two completely separate types of objects — asteroids and comets — is a key part of what makes these objects so interesting."

Related: The 'megacomet' Bernardinelli-Bernstein is the find of a decade. Here's the discovery explained.

Despite its comet-like characteristics, the object's orbit is definitely that of an asteroid: It quietly loops around the sun in the outer portion of the asteroid belt that falls between Mars and Jupiter, circling once every 5 years or so.

But this summer, astronomers looking through data gathered by the Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) survey in Hawaii on July 7 noticed that the object was sporting a tail. The feature showed up in additional observations made by a telescope at Lowell Observatory in Arizona. Scientists then checked previous observations made by other facilities, and spotted the tail again in images gathered on June 11 by the Zwicky Transient Facility in California.

In those observations, the object was heading away from the sun, having made its closest approach, or perihelion, on May 14. (While a comet's close approach is much more dramatic than that of a typical asteroid in the main belt, all objects orbiting the sun move closer and farther away from it over the course of an orbit. Earth's perihelion, for example, falls in early January.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Meanwhile, other scientists looked through observations of 2005 QN173 gathered by the Dark Energy Camera in July 2016, the last time the object was around perihelion — and lo and behold, here too they spotted a tail.

Activity around perihelion matches the profile of a comet: increasing heat from the sun turns frozen ice into gas, a process called sublimation. Typical comets spend most of their time far enough away from the sun for activity to be frozen — literally.

"Most comets are found to come from the cold outer solar system, beyond the orbit of Neptune, and spend most of their time there, with their highly elongated orbits only bringing them close to the sun and the Earth for short periods at a time," Hsieh said. "During those times when they are close enough to the sun, they heat up and release gas and dust as a result of ice sublimation, producing the fuzzy appearance and often spectacular tails associated with comets."

Of the half a million objects scientists have examined in the asteroid belt, this is the eighth one that scientists have been able to confirm has been active multiple times, and it's one of only 20 suspected "main-belt comets."

The new research included old observations dug out of the archives of various instruments originally gathered between 2004 and 2020 at times when the comet wasn't active, in order to better understand the object itself. Those observations suggest that the nucleus or head of the comet is about 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) wide, according to the statement.

Then, the scientists incorporated fresh observations of the object made by a host of instruments this July and August aimed at better understanding the activity of the strange main-belt comet. In particular, the researchers were able to measure the object's tail, which in July stretched 450,000 miles (720,000 kilometers) long, a little less than twice the distance from Earth to the moon.

But despite its massive length, the tail isn't all that wide, which poses the scientists a new puzzle.

"This extremely narrow tail tells us that dust particles are barely floating off of the nucleus at extremely slow speeds and that the flow of gas escaping from the comet that normally lifts dust off into space from a comet is extremely weak," Hsieh said.

"Such slow speeds would normally make it difficult for dust to escape from the gravity of the nucleus itself, so this suggests that something else might be helping the dust to escape," Hsieh added. One explanation could be that the nucleus is spinning so quickly that it shoots extra dust into space, but the scientists don't have enough observations to be sure.

The scientists are marking their calendars for February 2026, when the object can be seen from the Southern Hemisphere and also reaches the distance from the sun at which it may become active again.

The research is described in a paper accepted to The Astrophysical Journal Letters and available to read as a pre-print on arXiv.org; the research was also presented on Monday (Oct. 4) at the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences conference being held virtually this week.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.