An asteroid trailing after Mars could actually be the stolen twin of our moon

The asteroid in question, called (101429) 1998 VF31, is part of a group of trojan asteroids sharing the orbit of Mars.

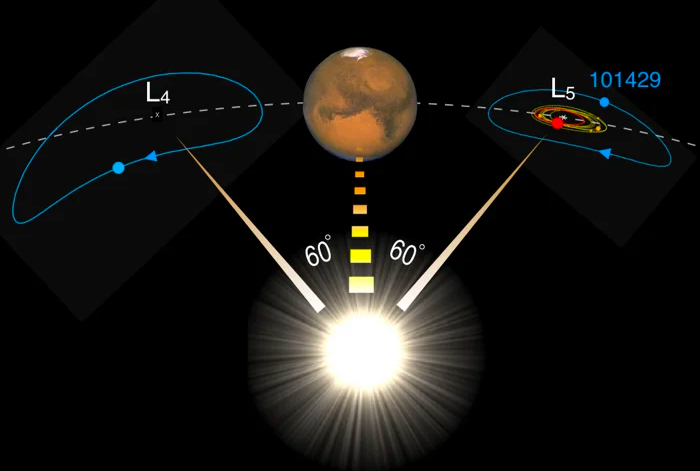

Trojans are celestial bodies that fall into gravitationally balanced regions of space in the vicinity of other planets, located 60 degrees in front of and behind the planet.

Most of the trojan asteroids we know about share Jupiter's orbit, but other planets have them too, including Mars and Earth too.

What makes (101429) 1998 VF31 (hereafter '101429') interesting is that among the Red Planet's trailing trojans (the ones that follow behind Mars as it orbits the Sun), 101429 appears to be unique.

The rest of the group, called the L5 Martian Trojans, all belong to what's known as the Eureka family, consisting of 5261 Eureka – the first Mars trojan discovered – and a bunch of small fragments believed to have come loose from their parent space rock.

101429 is different, though, and in a new study led by astronomers from the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium (AOP) in Northern Ireland, researchers wanted to examine why.

Using a spectrograph called X-SHOOTER on the European Southern Observatory's 8-m Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, the team examined how sunlight reflects off 101429 and its L5 kin in the Eureka family. Only, it looks like 101429 and the Eureka clan aren't kin after all, with the analysis revealing 101429 shows a spectral match for a satellite much closer to home.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

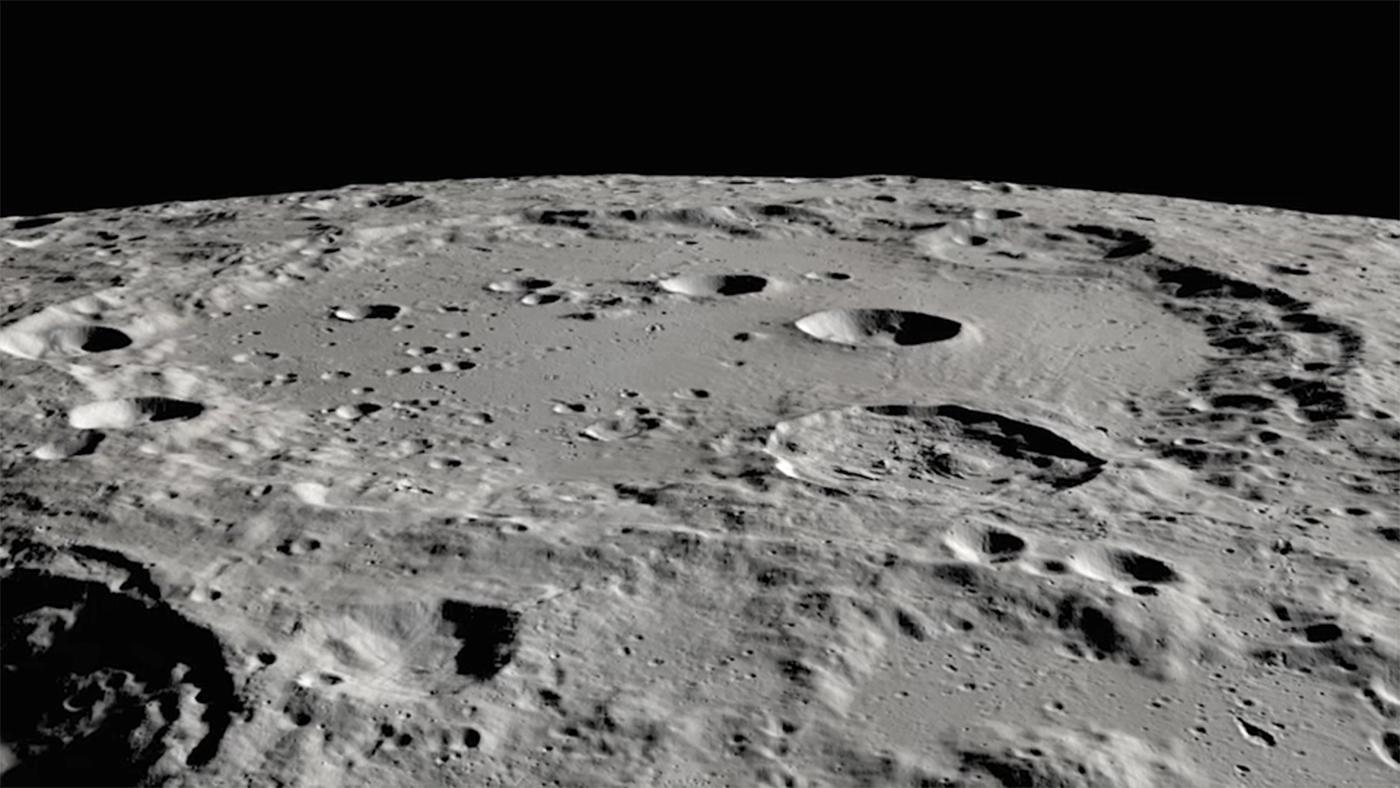

"The spectrum of this particular asteroid seems to be almost a dead-ringer for parts of the Moon where there is exposed bedrock such as crater interiors and mountains," explains AOP astrochemist Galin Borisov.

While we can't be sure yet why that is, the researchers say it's plausible that this Martian trojan's origins began somewhere far removed from the Red Planet, with 101429 representing a "relic fragment of the Moon's original solid crust".

If that's true, how did the Moon's long-lost twin end up as a trojan bound together with Mars?

"The early Solar System was very different from the place we see today," explains lead author of the study, AOP astronomer Apostolos Christou.

"The space between the newly-formed planets was full of debris and collisions were commonplace. Large asteroids [planetesimals] were constantly hitting the Moon and the other planets. A shard from such a collision could have reached the orbit of Mars when the planet was still forming and was trapped in its Trojan clouds."

It's a captivating idea, but the researchers say it's not the only explanation for 101429's past. It's also possible, and perhaps more likely, that the trojan instead represents a fragment of Mars chipped off by a similar kind of incident impacting the Red Planet; or it might just be a commonplace asteroid that, through the weathering processes of solar radiation, ended up looking just like the Moon.

Further observations with even more powerful spectrographs might be able to shed more light on this question of space parentage, as could a future spacecraft visit, the team says, "which could, en route to the Trojans, obtain spectra at Mars or the Moon for direct comparison with the asteroid data".

The findings are reported in Icarus.

This article was originally published by ScienceAlert. Read the original article here.

Peter Dockrill is the Deputy Editor of ScienceAlert. With a background in law and technology journalism, Peter's work has appeared in APC, TechLife, PC User, Money, The Laws of Australia, and The Newcastle Law Review. Peter's science reporting was featured in "The Best Australian Science Writing 2018" anthology. He won most entertaining writer at the Consensus IT Writers Awards, and he was a finalist at the Australian IT Journo Awards. When not working, Peter likes spending time with friends, cooking, and making music. He lives in Newcastle, Australia with his wife, their two lovely daughters and a dog called Belle.