Astronaut-explorer Richard Garriott makes record-breaking dive to deepest point on Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

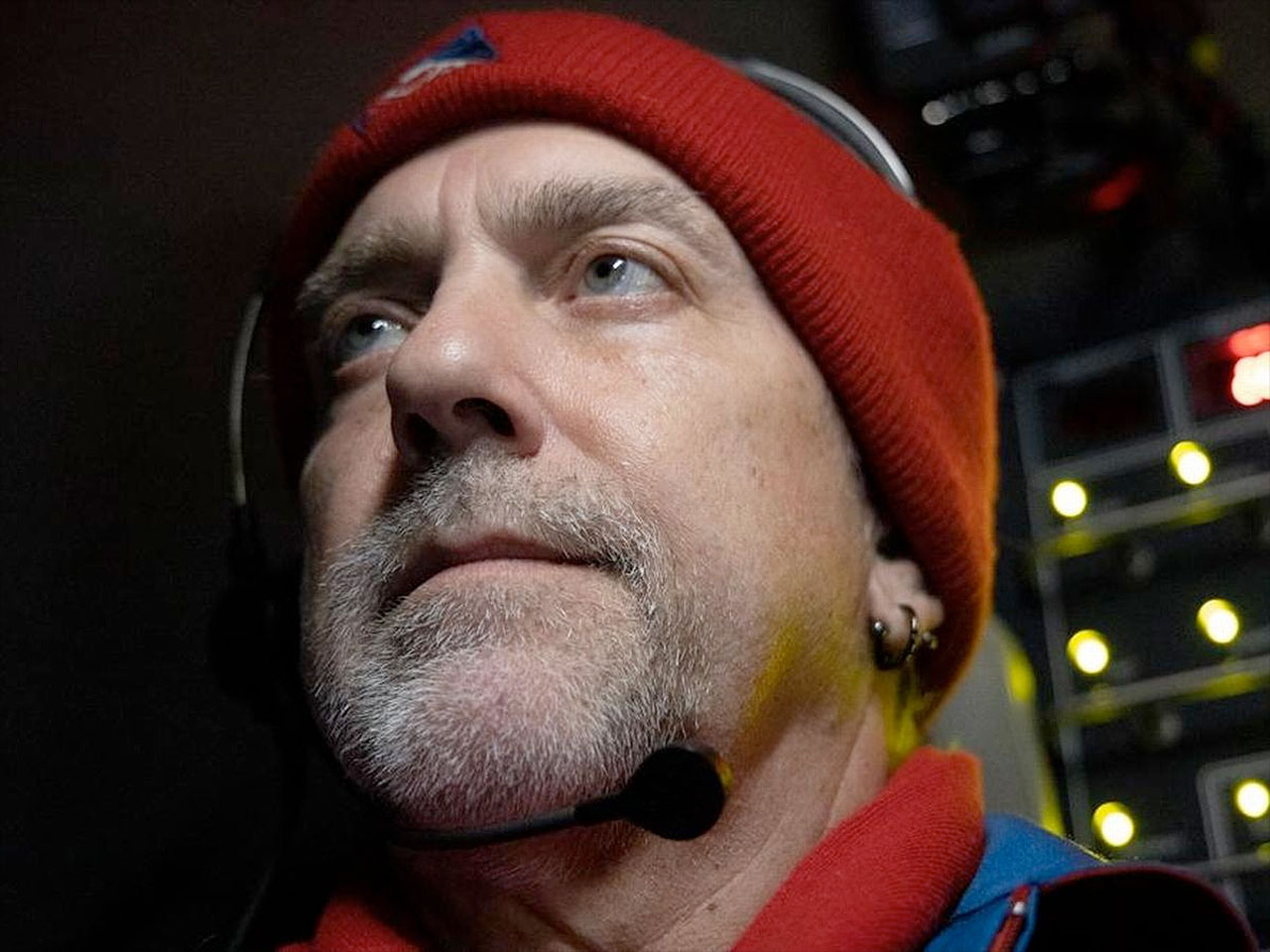

The son of a NASA astronaut and a video game pioneer who previously traversed both the North and South poles and funded his own trip to the International Space Station, Garriott completed a dive to Challenger Deep, the lowest point on Earth, on March 1.

"I am the first person to go pole to pole, space and deep and the second person — first male — to go space [to] deep," Garriott told collectSPACE in a call while still at sea on Tuesday (March 2).

Garriott, who is the incoming president of The Explorers Club, made the dive on board the "Limiting Factor," the first commercially certified, full-ocean-depth deep submergence vehicle that was developed and funded by undersea explorer Victor Vescovo. It was aboard the same submersible with Vescovo as pilot that former NASA astronaut Kathy Sullivan became the first space traveler and first woman to dive to Challenger Deep — in August 2020.

Like Sullivan, Garriott made the trip as part of a series of dives aimed at surveying the Mariana Trench and collecting scientific samples. Garriott, together with his friend Michael Dubno (who was mid-dive when Garriott called from the surface support ship, the "Pressure Drop"), also brought along their own set of engineering and artistic experiments for the journey.

collectSPACE.com spoke with Garriott about his record-setting dive and the similarities it shared with his other adventures around, and off, the world. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

collectSPACE (cS): Though certainly the deepest, this was not your first dive. How did the four-hour descent to Challenger Deep compare to some of your other dives, such as to the Titanic and to hydrothermal vents aboard the Russian-built Mir submersibles?

Richard Garriott: What's interesting about Limiting Factor is that it's going to more than twice the depth than I'd ever been previously and, as it turns out, that is mightily more difficult. To find equipment that can operate at half that depth is already virtually non-existent. So to find or create equipment that can operate at double that depth is even harder. They have had to overcome some amazing engineering problems, starting with just how to keep the passengers alive.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The 9-centimeter-thick (3.5-inch) titanium hull is the smallest vehicle I've ever been in, although it felt roomier than a Soyuz [Russian spacecraft] because there is less people and material on the inside. So you actually feel very comfortable, but the interior diameter only starts at about 1.46 meters (4.79 feet) and shrinks to about 1.4 meters (4.59 feet) as the pressure builds on the outside.

The temperature also goes from quite warm on the surface here in the tropics [near Guam] to just right about freezing as you get down into the depths. It gets colder and colder.

The light disappears almost immediately. Most other submarines in the world operate within a few hundred meters of the surface where there is generally still a little bit of light still available. This one is descending so fast and so far that it becomes truly pitch black outside the viewport mere moments after you depart and so you're falling through the inky blackness for most of the four-hour descent.

cS: During the descent, do you just sit there for four hours? Is there something to do? Do you take a nap?

Garriott: I had taken with me a lot of things that I wanted to do on the interior [of the submsersible] associated with the outreach that I was doing with the schools across the U.S. and even more in the UK. Whether it was photography as part of a project that students were working on in concert with the company Canon or sharing and filming some of the artwork that school kids had created, or reading some poetry the kids had had written specifically for this challenge, that kept me busy for the downward journey and the upward journey.

In fact, let me just mention something about the poetry, just because I think it was the one [activity] for me that was the most surprising.

It's really common to decorate [and dive down with] styrofoam cups to show how they get compressed [by the pressure] in the depths because it is a fun little keepsake, but it was a gentleman from the National Organization for Teaching English that came up with a challenge for students that basically said to stay alive and do work at this depths in the ocean, the developers of the submarine and the scientists on board have to take only the minimum number of things with them on the interior, things absolutely needed for life support and for experiments.

The challenge to the kids was to write a poem called a cinquain, a five line poem of 22 total syllables, where the you're only allowed two, four, six, eight and two syllables per line. So when you're going to write a poem about how to dive down to the deepest point of the ocean, you have to choose not only every word, but frankly, every syllable very carefully.

It turned out that was super popular for people to get involved in. Not only did kids across all of the UK schools submit really clever poems, but as soon as people on Twitter started hearing about it, I started hearing back from students across almost every continent on Earth. And I started hearing from relatives I didn't even know I had from various parts of the country. All of them wanted a chance to participate.

Even my own kids and family got involved in writing these. And I wrote a few myself and even Victor Vescovo, the submarine developer and pilot, who was with me, he was enjoying these so much, he wrote one on the spot. He wrote one down in the Challenger Deep at the bottom and recited it for the kids from there at the bottom, too.

That kept us busy for what otherwise could have been long spans of time on the descent and ascent. Reading poetry turned out to be just big fun and much more interesting than I expected. So there was very little time to rest or be bored. Traditionally everyone takes a movie for the way up. My selection was "Das Boot," the German submarine warfare movie, but we only watched an hour of it because we were still so busy doing other activities.

cS: What did you see and do when reached the deep, the bottom of the ocean?

Garriott: Our dive plan was to drop down first right into the deepest part of the eastern pool, which is the deepest part of the Mariana Trench, just to check off the box that we had reached the deepest point and to leave a geocache, which we did.

We left behind a 6-inch-square [15 cm] titanium plate connected to a 6-foot [1.8 m] line of Kevlar with a syntactic foam float. On all sides of the float and all sides of the titanium is the geocache numerical identifier and a secret word. The reason for the secret word is so that the only people who will be allowed to claim that they've been the ones to find it are those who know the secret word, ensuring that they've actually visited.

So we successfully deployed [the geocache] in the center of the deepest point on Earth and then we cruised for about an hour across the sea floor.

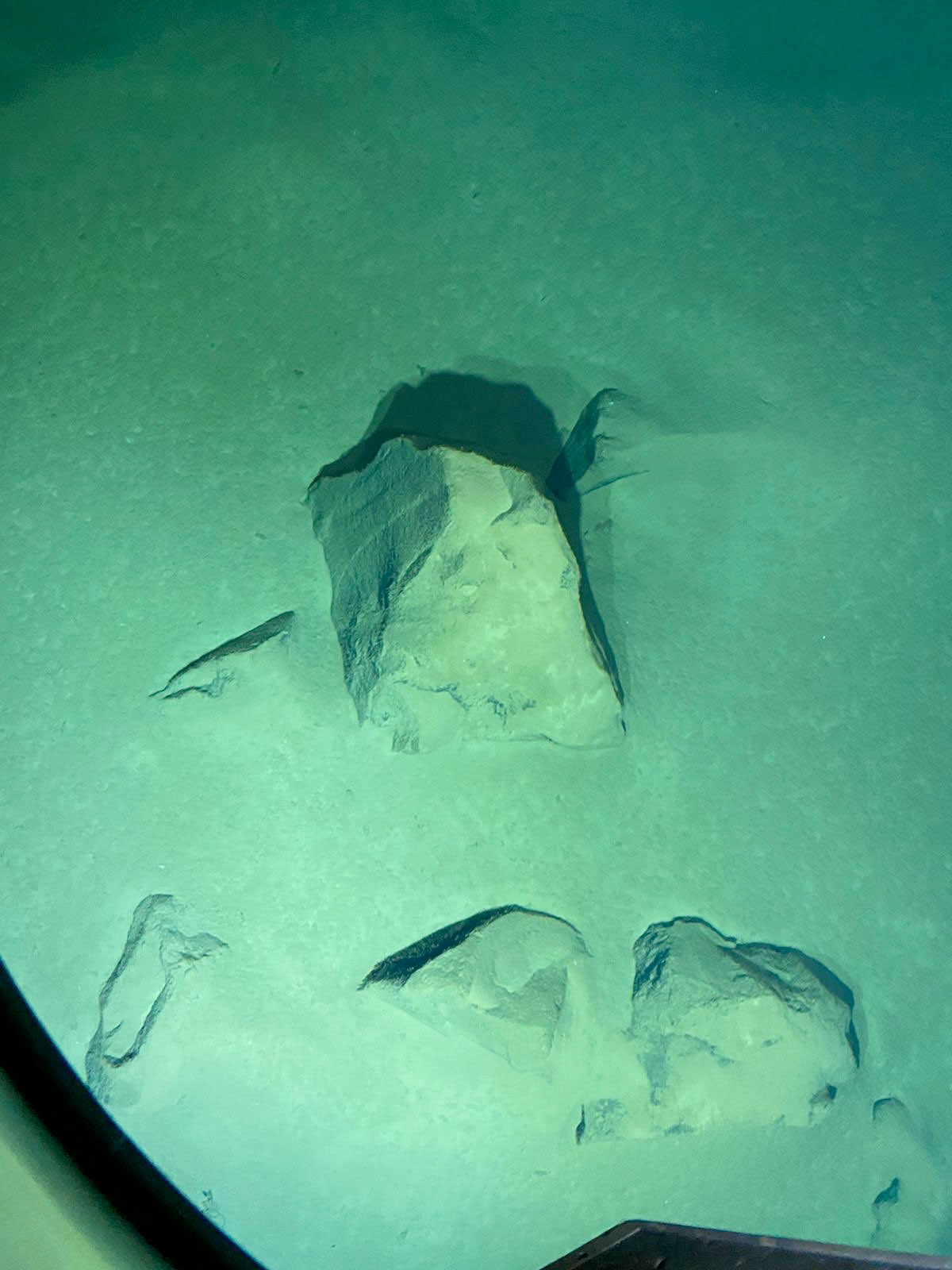

The sea floor down there, right where you land, is what I'm describing as the 'abyssal plain.' It's a desert of sorts. The bottom condition is both flat and has a very silty, murky bottom where the detritus from life seven miles [11 km] above it in the water column — whether it's scales or dirt or dust or the rotting corpses of fish above — sort of slowly all rains and settles down here at the bottom. While at some point down below us you would get into what you might traditionally call mud, the actual entire surface is covered with maybe a foot thick [0.3 m] of this talcum powder fluff that is more like what you might imagine, or you might've seen in a Build-A-Bear Workshop where they have the fluff they shove into stuffed toys.

There's not really even a surface that looks particularly hard. It is very, very, very, very delicate. But there's actually quite a bit of life down there. We saw almost every few feet or at least every dozen feet, one of these almost translucent crustaceans of a few inches long that would scoot around all over the bottom to make a meager existence out of the tiny amount of organic matter that makes it down there for food.

Then, as we crossed this abyssal plain, we actually ran into our first bit of humanity, which was a 7-mile-long [11 km] cable that had been previously attached to a remotely-operated vehicle. It's worth noting that last summer when Victor was down here, this was not there. And between that visit and our visits, a Chinese crew had been out here with both one free diving submersible and one remotely operated vehicle, the latter to photograph the submarine.

It's a fairly common practice for those who use these extremely long tethers to jettison it and the problem with that is it creates an incredibly difficult hazard for submarines because it's 7 miles long and loops and curls all over the sea floor and you can't see it until you're really in it. We saw it first crossing our paths in one direction and we were shocked to see it, a little bit alarmed and concerned. Then we saw the same cable, or presumably the same cable again, crossing our path the other direction.

cS: Before you dove, you said you had intentions to try to collect geological samples from where the Pacific plate is being subducted below the Philippine Sea plate (which is why the Mariana Trench exists). Were you successful?

Garriott: We were unable to get a rock back. We were having both some electrical problems and, unrelated, we were having some trouble with the manipulator arm. It turned out to be a software glitch. And then there was the condition of the rocks.

Even though we were in the rockfall, all the rocks that we could see were still covered in this very deep murky soup that I described. Only little corners of large rocks stuck out and we really needed to find one that was small enough for the manipulator arm to pick up. Because of the covering of fluff, we couldn't see the small rocks, much less reach in to pick them up. If you came close to this murky bottom, you get browned out by the kicking up of that silt that might take hours to settle again. And so we were unable to get a rock. That is a task we will leave to the next explorers.

cS: One of your personal projects was to try to use the pressure outside of the submersible to hydroform, or mint, tokens. How did that go?

Garriott: Oh, yes! We made a double-sided die with 18 bolts or so around a ring to clamp on metal plates to try to hydroform. The side that we put copper on did perfectly. It actually is a marvelous little, three-inch [7.6 cm] impression that was made across the die.

What's interesting is that there were still some air pockets below that copper plate, which means that a millimeter or two of copper is technically enough to where if you were to drill a hole in the side of the submarine — which you do not do — but if you did and covered it with even just a thin copper plate, it would bow into that quarter-inch [0.6 cm] hole, but wouldn't break, it wouldn't pop.

It's actually fascinating that on the one hand, this depth and pressure is awesome to try to think about how to build equipment to survive within it. On the other hand, it's similarly awesome just how a simple experiment like hydroforming can show that even a thin sheet of metal, if it's supported in the right way, will not break and still resist that amazing pressure.

The other side of the die we had made with brass and the brass stayed stiffened straight up until water managed to encroach on the sides and fill the other half of the die. So we've added a little special lubricant that they use on the hatches that helps seal from water. We'll see if that works.

cS: So now that you've conquered the deep, how would you compare it to your past adventures? Does one top the others or how would you rank them?

Garriott: Well, space will be hard to beat, so space still wins. But the one thing that all of the locations share is that when you go to someplace that's this extreme, the laws of physics really do seem to change profoundly.

In space, the obvious one is floating around 24/7. Not feeling gravity is obviously a fundamental change in the physics associated with your life.

In Antarctica, it's the complete lack of being able to tell distance because there's no specular hazing, there's nothing like roads or telephone poles to give you a sense of perspective. And so large rocks far away and small rocks close up look the same. It's a fascinating place to be because of how sight and sound works and the same is now true for these incredible depths where you can measure the hull being crushed around you.

I took a digital tape measure and the submarine shrunk by 6 millimeters [0.2 inches] as went down to the depths. The pressure was so great that even things like the acoustic phones, which were made for communicating underwater, barely work at those depths.

Water is non-compressible but in fact it does compress at least a little. The density of the water becomes greater and greater at these enormous depths. Our descent rate at the beginning was a couple of meters per second, but by the time we got to the bottom, the water itself became so dense that we slowed down to under a half a meter per second, just because we were almost becoming neutrally buoyant at the bottom, despite the fact that we were getting smaller by being crushed.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2021 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus