5 reasons hyenas like Harley Quinn's 'Bruce' are amazing

They have incredible adaptations that even a supervillain would envy.

D.C. Comics' manic pixie criminal Harley Quinn gets it: Hyenas are delightful.

In the movie "Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn)" (2020, Warner Bros. Pictures), Ms. Quinn (Margot Robbie) acquires some new partners in crime, including a large and very intimidating hyena that she bestows with a pink collar and names Bruce — "after that hunky Wayne guy," Quinn says.

While hyenas are ill-suited to be pets in real life, they are nonetheless fascinating animals that have complex social lives and astounding physical capabilities that even a supervillain would envy.

Here are just a few of the reasons why we think hyenas are awesome.

Related: Image gallery: Hyenas at the kill

They communicate using 'butter' from their butts

While hyenas do share messages with their signature cackle, some of their most important communications are generated at their other end. They produce a sticky, smelly secretion in their anal glands, and they smear it on grasses to send signals to other hyenas.

This malodorous paste — known as "hyena butter" — smells similar to wet mulch or cheap soap, Kevin Theis, an ecologist at Wayne State University in Michigan, previously told Live Science. Its distinctive scent is actually the product of bacterial communities that inhabit hyenas' scent glands, and changes in the bacteria can affect the "messages" that hyenas are sending with their butts, Theis explained.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They are 'incredible bone-crushing machines'

Hyenas' skulls and jaws are so powerful that they can crush the leg bones of large animals such as wildebeests and rhinos, according to Jack Tseng, an assistant professor with the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences at the University at Buffalo in New York.

Tseng studied the bone-crushing abilities of hyenas by scanning their skulls and creating computer models to calculate their bite force and tooth structure, he said in an animated video describing his research.

However, not all hyenas have strong jaws. One notable exception is the aardwolf (Proteles cristata), a hyena species that feeds primarily on termites, Oliver Höner, a senior researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research in the Department of Ecology, and co-founder of The Ngorongoro Hyena Project, told Live Science in an email.

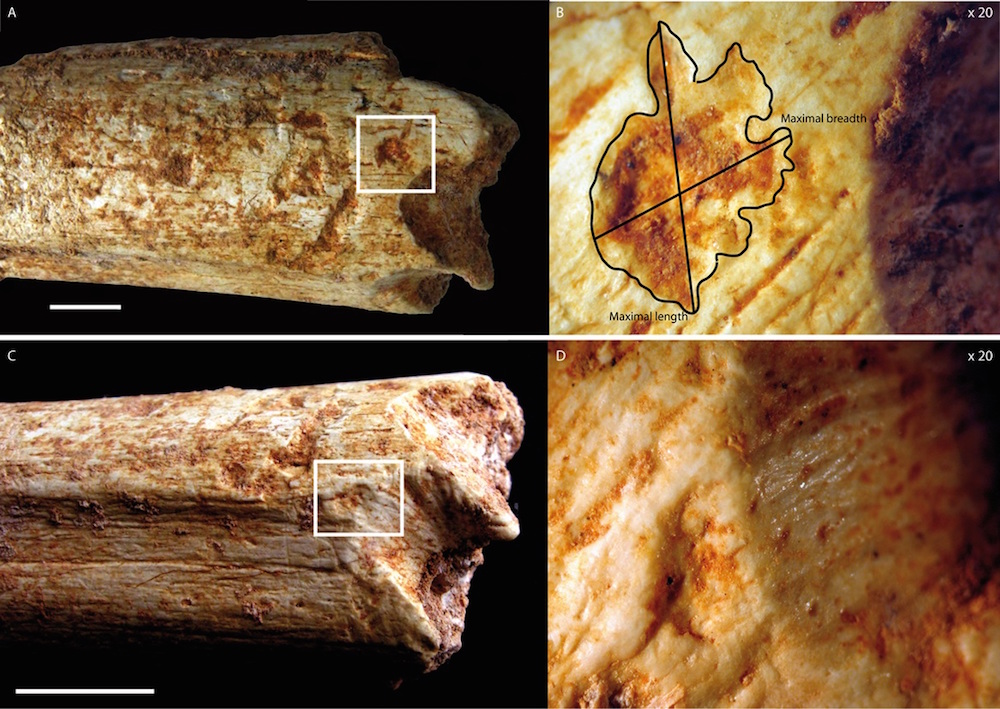

Ancient hyenas dined on human relatives

Early humans once competed with ancient hyenas for space and resources — and sometimes humans ended up on the menu.

Tooth marks and cracks crisscrossed a femur found in a Moroccan cave and dating to around 500,000 years ago, and the marks suggest that a large carnivore, likely a hyena, chewed on the bone. Other bones in the cave belonged to the hominin Homo rhodesiensis, an extinct lineage of early humans, but it is unknown if the ancient hyena killed its hominin prey or scavenged the remains.

By looking at coprolites, or fossilized dung, scientists have also found evidence that hyenas ate our human relatives. In 2009, researchers discovered dozens of animal hairs preserved in hyena coprolites from South Africa that dated to 200,000 years ago; an analysis revealed that humans — early Homo sapiens or our close relative Homo heidelbergensis — were the closest match for the tiny hairs.

They are better at cooperating than chimpanzees

Scientists discovered that hyenas can work together to get a reward, and they collaborated more readily and required less preparation than chimps or other primates did in similar experiments.

Researchers tested captive pairs of spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) with a rope-tugging challenge: The hyenas received a food reward if they pulled two ropes at the same time. Not only did the hyenas cooperate to succeed at the task, they did so with no prior training and mostly without vocalizing — they watched and learned from each other in near-complete silence.

"The first pair walked in to the pen and figured it out in less than two minutes," said Christine Drea, an evolutionary anthropologist at Duke University in North Carolina who led the experiments. "My jaw literally dropped," Drea said.

They once ranged as far north as the Arctic

Today, hyenas are found only in Africa. But their ancestors first appeared about 20 million years ago, in Europe or Asia, and some of those ancient predators crossed into North America over the now-submerged Bering Strait land bridge, according to a pair of fossil teeth dating between 1.4 million and 850,000 years old that place the extinct hyena Chasmaporthetes as far north as the Arctic, in Canada's northern Yukon Territory.

These wolf-size hyenas vanished from North America between 1 million and 500,000 years ago, perhaps due to competition from ice age carnivores such as the giant short-faced bear Arctodus and the bone-cracking dog Borophagus.

Chasmaporthetes is just one of around 100 species of hyenas that are known from the fossil record, according to a study published in 2005 in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution. Today, there are only four hyena species: spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta), striped hyenas (Hyaena hyaena), brown hyenas (Parahyaena brunnea) and aardwolves (Proteles cristatus).

- My, what sharp teeth! 12 living and extinct saber-toothed animals

- 10 extinct giants that once roamed North America

- Ice Age animal bones uncovered during LA subway excavation

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.