Ancient ritual bloodletting may have been performed at carvings found in Mexico

Archaeologists found 30 of these carvings in southern Mexico.

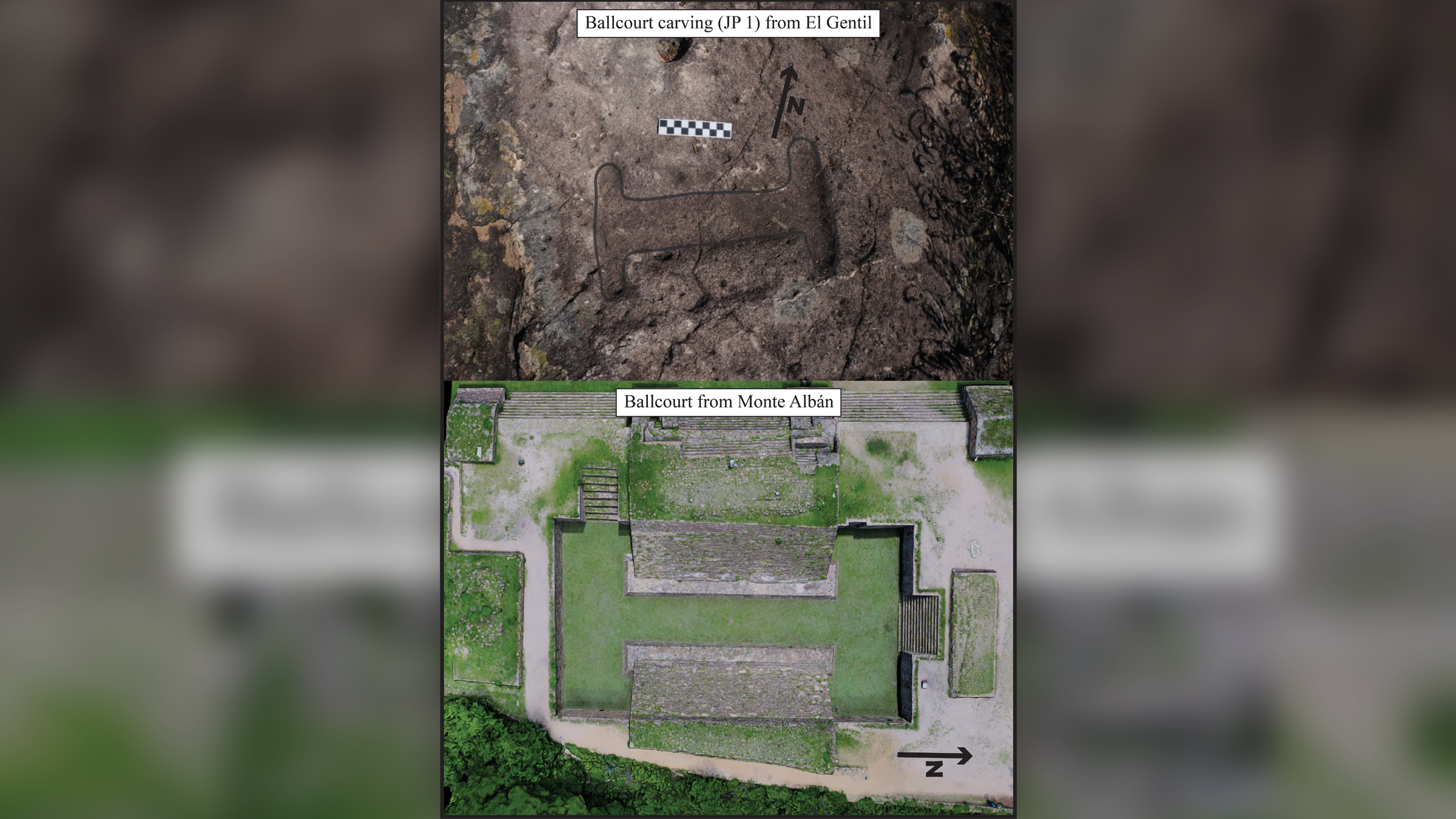

Archaeologists in southern Mexico have discovered 30 carvings depicting capital I-shaped ballcourts cut into rocks. These carvings may have been used in ceremonies involving water and "ritual bloodletting," new research finds.

The carvings, in the ancient settlement of Quiechapa, are badly weathered, but small features in a few cases can be made out, such as one carving that appears to show a bench in the ballcourt.

"Ballgames were of great significance to people throughout ancient Mesoamerica," study researcher Alex Elvis Badillo, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Systems at Indiana State University, wrote in an article published Jan. 11 in the journal Ancient Mesoamerica.

The shape of the ballcourts changed over time, and the rules of the ballgame are not known and may also have changed. The ballgame was played at least as early as 3,600 years ago, involved a rubber ball and two opposing sides, and was played from what is now the American Southwest, in Arizona and New Mexico, to as far south as Colombia in South America, Live Science previously reported. Much is still unknown about the ballgame but it appears to have held some level of religious and ceremonial importance scholars believe.

Related: Ancient 'tomb' unearthed in Guatemala turns out to be Maya steam bath

It's unclear when exactly these carvings were crafted. Quiechapa dates back at least 2,300 years and possibly earlier, and people in southern Mexico began using I-shaped ballcourts around 2,100 years ago, Badillo told Live Science in an email, adding that "I think it is logical to suggest that these carvings would have been made sometime after [100 B.C.], however, it is hard to say when these carvings were made."

The researchers found the 30 carvings in natural rock outcrops at two sites in the area. "This is the highest density in which this type of ballcourt representation occurs throughout Mesoamerica," Badillo wrote in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

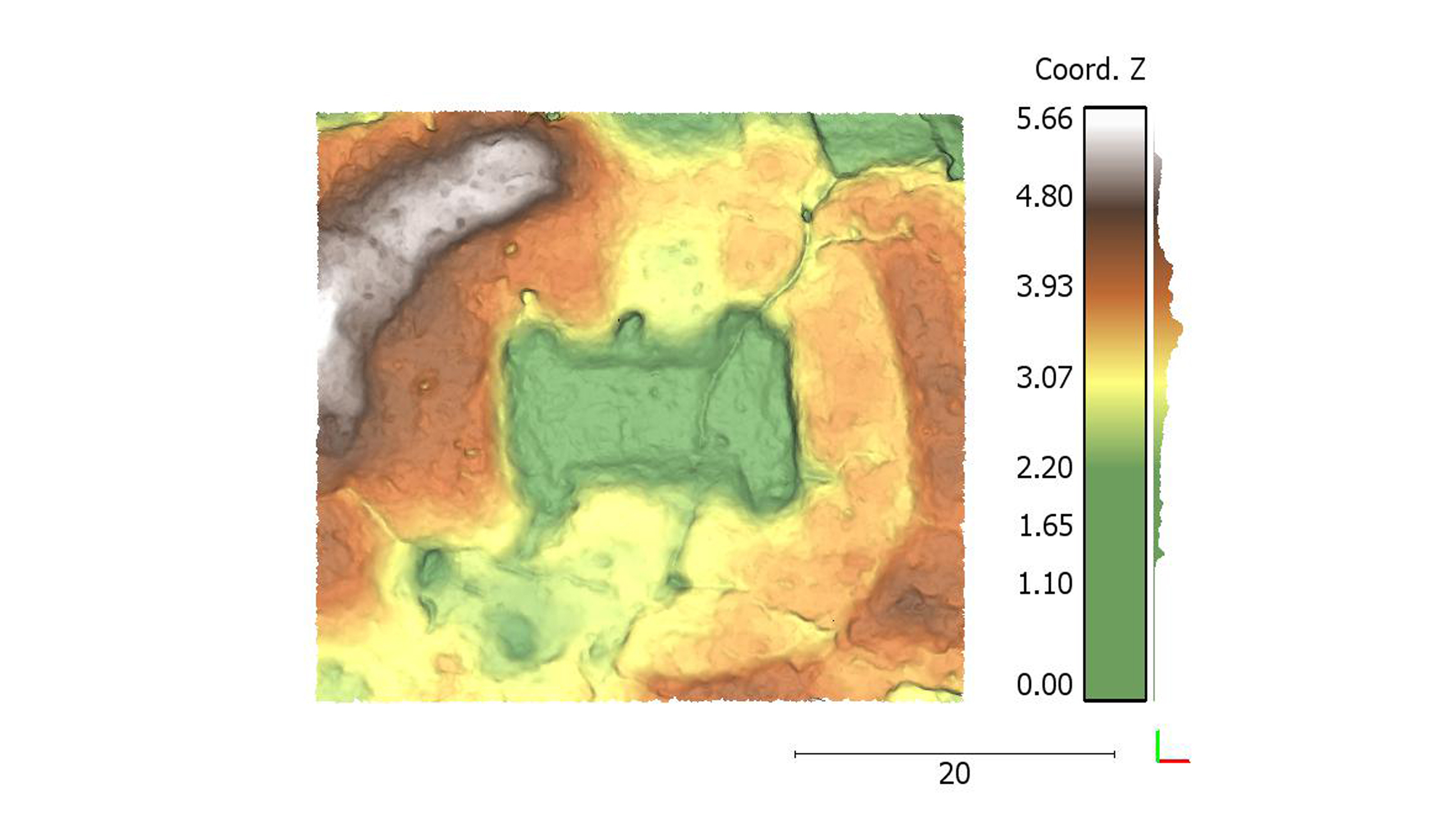

The biggest carving is 13.4 inches (34.1 centimeters) long while the shortest is 3.1 inches (8 cm) long, Badillo said. The archaeological team documented the carvings using structure-from-motion (SfM) photogrammetry. In this system, photos were taken of the carvings from different angles and uploaded to a computer program, which used the images and an algorithm to create a virtual, 3D representation of the carvings.

Bloodletting rituals

It's not clear what the carvings were used for, but the researchers suggested that ancient Mesoamericans may have used them for rituals. The Spanish priest Juan Ruiz de Alarcón (lived 1581 to 1639), who lived in what is now Mexico following Spain's conquest of the area in the 16th century, "describes certain rituals during which a [Mesoamerican] priest would have people spill blood into small cavities that they had made in stone," Badillo wrote in the study, noting that those cavities could include the ballcourt carvings.

"The idea that water and blood are considered sacred and are symbols that are central to Mesoamerican cosmology is well established in the [scholarly] literature," Badillo wrote in the paper.

"These seemingly inert stone carvings in Quiechapa's landscape may have been part of deeply meaningful and active social performances that included ritual bloodletting for many possible purposes, including maintaining balance and agricultural fertility, marking important moments in time, or fomenting intra- and inter-community bonds," Badillo wrote.

However, he cautioned that until more evidence is found, archaeologists can't be certain that rituals were performed at these carvings.

Badillo presented the findings at the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) annual meeting held in Chicago from March 30 to April 3. The ballcourt carving surveys were carried out as part of the Quiechapa Archaeological Project (PAQuie).

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.