Mystery of 15th-Century Bayeux Tapestry Solved

The elaborate and enormous tapestry was made to grace a specific spot.

A medieval tapestry that tells the story of the Norman conquest of England over 230 feet (70 meters) of wool yarn and linen has just divulged one of its secrets. Though the origins of this magnificent work of textile, called the Bayeux Tapestry, are murky, researchers now think they know why the tapestry was made: to be displayed in the nave of the Bayeux Cathedral.

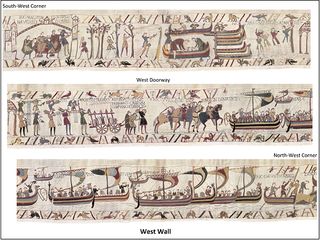

The dimensions of the cloth mean it would have fit perfectly into the 11th-century nave of the Bayeux Cathedral in Normandy, France, the researchers reported Oct. 23 in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association. The narrative of the embroidery would have even fit around the spacings of the nave's columns and doorways.

The first written record of the tapestry is in the Bayeux Cathedral's inventory from 1476, so the idea that the tapestry had been commissioned for the cathedral in the 11th century was always the simplest explanation, according to study author Christopher Norton, an art historian at the University of York in England.

Related: 30 of the World's Most Valuable Treasures That Are Still Missing

"This general proposition can now be corroborated by the specific evidence that the physical and narrative structure of the tapestry are perfectly adapted to fit the (liturgical) nave of the 11th-century cathedral," Norton said in a statement.

The Bayeux Tapestry is not technically a tapestry, as its design is embroidered onto the linen rather than woven. According to the Bayeux Museum, the tapestry was likely commissioned by Bishop Odo, the half-brother of William the Conqueror, the Norman leader who led the conquest of England and won the crown in 1066. William's exploits are depicted on the tapestry, which concludes with the decisive battle of the conflict, the Battle of Hastings. No one knows exactly who made the embroidery, but researchers have concluded that the work was probably done in England and that the stitching was likely the work of women, as embroidery was a largely female occupation in medieval England.

Norton used measurements from the modern Bayeux Cathedral, combined with historical records of what the nave, or central part of the building, would have looked like when it was first built more than 1,000 years ago. He compared the dimensions to the dimensions of the tapestry, taking into account potential shrinkage of the material and missing sections. The tapestry would have fit along the north, west and south walls of the nave, Norton found, ending just before the cathedral's choir screen.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings aren't entirely academic. French President Emmanuel Macron has promised to loan the Bayeux Tapestry to the United Kingdom, an event that would occur in 2022 or 2023, if the tapestry is shown to be in good enough condition to travel.

The findings might inform how the tapestry is displayed going forward. Norton recommends it be displayed along three sides of a rectangular space, mimicking how the original artists meant for the work to be seen.

Currently, the Bayeux Museum displays the tapestry in a horseshoe shape, though in the past the tapestry has been subjected to a variety of storage and display schemes. It was displayed annually at Bayeux Cathedral until 1803, when Napoleon had it displayed at his museum in Paris. Beginning in 1812, the tapestry was kept rolled-up in Bayeux's city hall; a custodian would hand-crank a spool to unwind the tapestry for display, according to the Bayeux Museum. The tapestry has been at its current location in Bayeux since 1983. During the proposed loan to the U.K., city officials plan to build a new museum in Bayeux to receive the tapestry upon its return.

- 10 Epic Battles That Changed History

- Family Ties: 8 Truly Dysfunctional Royal Families

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.