Ancient 'bear dog' found in France named after child-murdering cyclops

A jawbone fossil confirmed how widespread these carnivores were millions of years ago.

With jaws equipped to tear the flesh from the bones of their prey, extinct carnivores known as "bear dogs" were powerful predators that prowled Asia, southern Africa, Europe and North America more than 7.5 million years ago. Now, researchers have unearthed the jawbone of one of these extinct carnivores in the Pyrenees mountain range in Europe, shedding light on just how deadly bear dogs were, and confirming how widely they were distributed around the world.

Bear dogs, an extinct group of land-based carnivores in the family Amphicyonidae, are not in the bear family (Ursidae) or the dog family (Canidae), though they possess physical features similar to animals from both groups.

The fossilized lower jawbone represents a new species and perhaps a new genus of bear dog. The researchers named the genus, Tartarocyon, which is a nod to Tartaro, a menacing one-eyed giant who, according to Basque mythology, resided in Béarn during the late 8th century B.C., in the southwestern region of France, where the fossil was discovered.

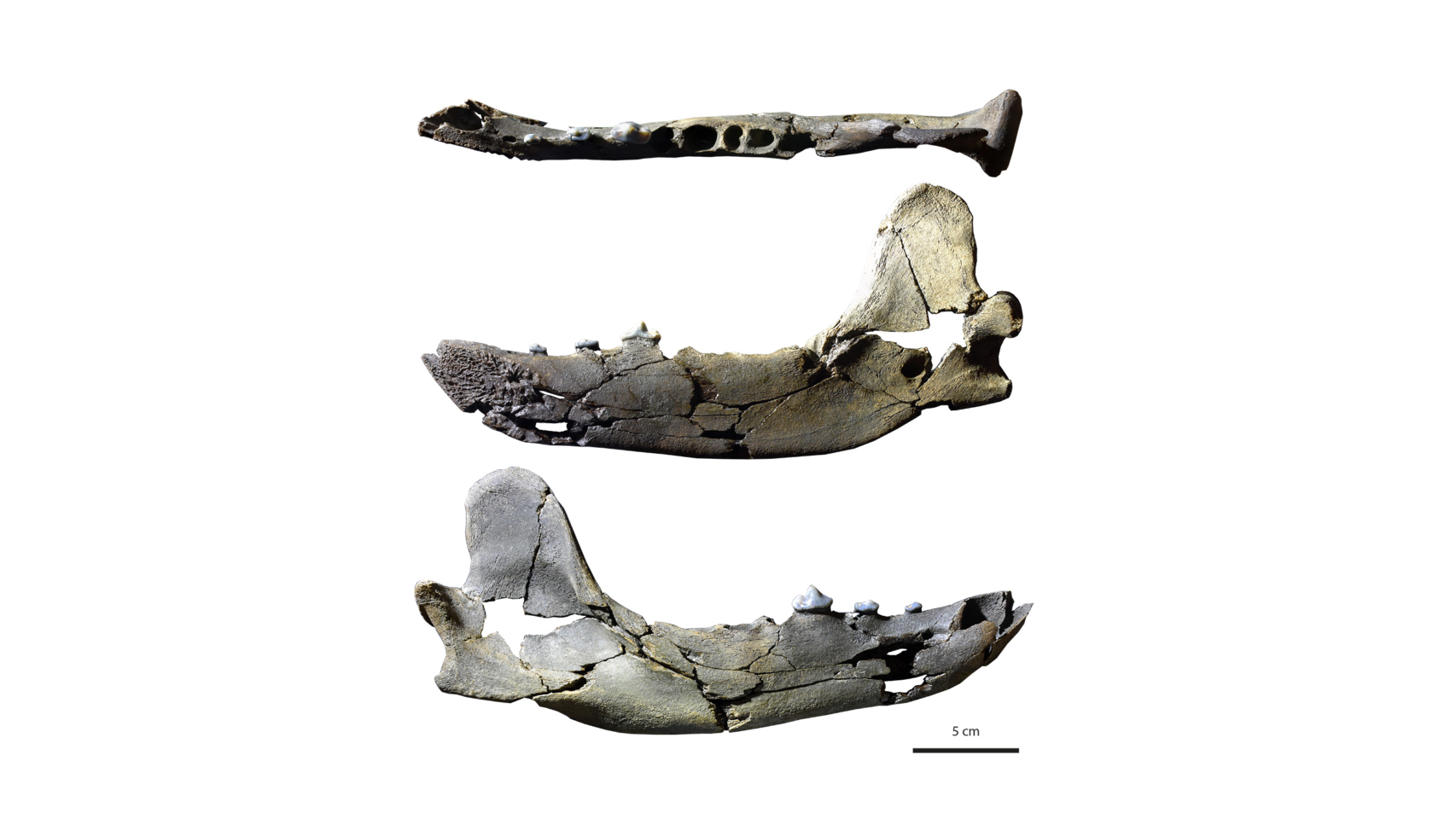

Measuring approximately 8 inches (20 centimeters) long, the mandible was embedded in a fossil-rich area of marine sediment studded with ancient shells.

The jawbone's most "striking" feature is its teeth, Floréal Solé, a paleontologist with the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science and lead author of the study, told Live Science in an email. A fourth lower premolar that had never been seen in the group before indicated to the researchers that the fossil belonged to a new genus and species, and hinted that it was likely a “bone-crushing mesocarnivore," the scientists reported in a new study.

Related: Lost fossil 'treasure trove' rediscovered after 70 years

Bear dogs were heavy-bodied and flat-footed walkers like bears, but they had relatively long legs and snouts like many dogs do. They lived during the Miocene epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago) and the animals varied widely in size, weighing from 20 to 705 pounds (9 to 320 kilograms). Researchers estimate that Tartarocyon was one of the bigger species, weighing approximately 441 pounds (200 kg).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Paleontologists aren’t sure how closely related bear dogs are to other animal families. "Depending on the palaeontologists, some argued that the Amphicyonids were phylogenetically close to the canids (dogs, wolves, jackals and foxes), while some concluded that these predators were closely related to the ursids (pandas and bears)," Solé said.

Solé added that it was "very interesting" to find a new premolar shape in a bear dog. Not only does it hint at the carnivore's bone-crushing abilities, it raises questions about how the evolution of this species may have diverged from the rest of the group, perhaps taking place in an area where populations were geographically isolated. "Tartarocyon, due to the original morphology of its teeth, may belong to a branch of the European Amphicyonids that evolved locally," Solé said.

Researchers from the Natural History Museum Basel in Switzerland used scanning technology and digital reconstructions to model the newfound mandible into a "3D puzzle," according to Bastien Mennecart, a paleontologist with the museum and co-author of the study.

"The mandible is almost complete, and well-preserved in 3D, with the small premolars also preserved," Mennecart told Live Science in an email. "The only missing pieces correspond to the two hammer blows [that were used] to collect the sediment."

The fossil was discovered on the northern edge of the Pyrenees, in a relatively isolated area that during the Miocene was flanked by a sea that covered much of southwest France, and a mountain range to the south. It is the first fossil of an Amphicyonid to be found in that region, suggesting that bear dogs roamed even more widely across Europe than once thought.

"This increases the geographic distribution of the Amphicyonids during the Miocene," Solé said. "Each discovery is important, even a small, isolated tooth."

The findings were published June 15 in the journal PeerJ Life & Environment.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.