Beating 'hearts on a chip' will travel to space on SpaceX's Dragon cargo ship tonight

Tissue-based models of the human heart are being sent to the International Space Station.

SpaceX's Dragon cargo ship is scheduled to launch Tuesday (March 14) evening, carrying nearly 6,300 pounds (2,860 kilograms) of cargo to the International Space Station (ISS). But among the spacewalk equipment, vehicle hardware and fresh fruit for the crew, there will be several small devices that contain something a little more unusual: beating human heart tissue.

The tissue will be used in two experiments — Cardinal Heart 2.0 and Engineered Heart Tissues-2 — which will test whether existing drugs can help prevent or reverse spaceflight's negative effects on the heart.

Research indicates that spaceflight can shrink the heart, because in microgravity, the heart muscles don't need to work as hard to pump blood through the upper parts of the body. In addition, the heart may change shape under the influence of microgravity, as blood shifts upward, out of the legs and abdomen and into the head and torso, causing the heart to swell, according to NASA.

Studies suggest that the heart also undergoes cellular changes associated with aging during spaceflight. Therefore, this research is not only critical to future space exploration but could also lead to improved treatments for age-related heart dysfunction and disease on Earth, Devin Mair, a doctoral candidate at Johns Hopkins University who's involved in Engineered Heart Tissues-2, said during a NASA news conference Tuesday.

Related: Tiny 'hearts' self-assemble in lab dishes and even beat like the real thing

The experiments are part of the Tissue Chips in Space initiative, a joint project of the National Institutes of Health and the International Space Station National Laboratory aimed at understanding the effects of spaceflight and microgravity on the human body, according to NASA.

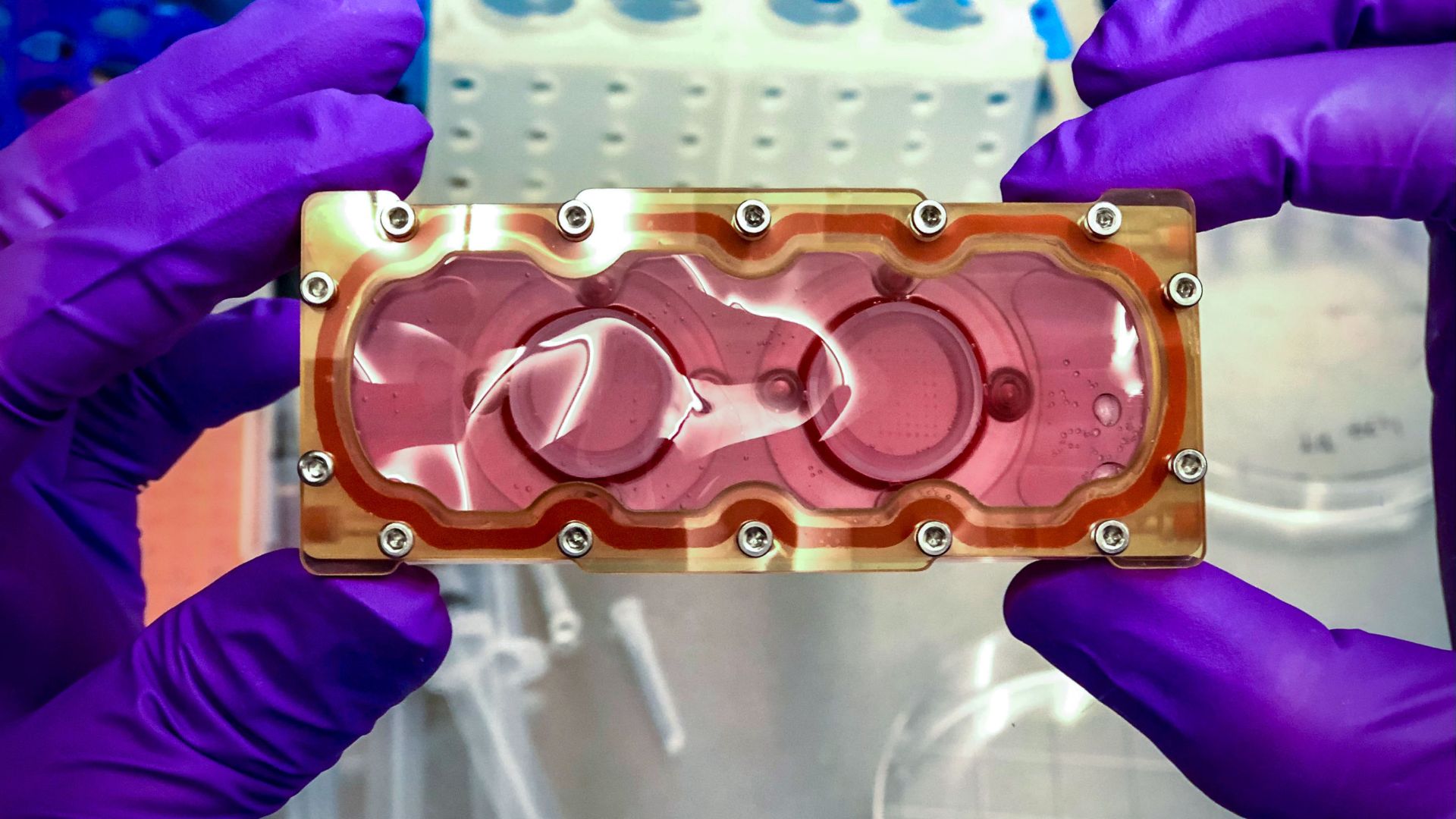

The Engineered Heart Tissues-2 experiment involves two devices that carry cardiomyocytes — the heart muscle cells that contract — in small, fluid-filled chambers. The muscle cells were grown from stem cells and coaxed into 3D shapes in the lab. They were then strung between two posts within each chamber, similar to how tennis nets are suspended between a pair of posts. One post contains a magnet that moves each time the muscle cells contract. A sensor tracks the magnet's movement, allowing the researchers to monitor muscle contractions in real time.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mair and his colleagues previously sent heart tissue to space in March 2020, and in that experiment, they observed signs that cells' mitochondria were malfunctioning, he said at the NASA news conference. Mitochondria provide power to cells and thus fuel the pumping of the heart, and their dysfunction has been tied to a variety of heart problems, including irregular heartbeat and heart failure. In an experiment launched on this trip to the ISS, the team will continue to study mitochondrial dysfunction, as well as test several existing drugs to see if they prevent or reverse the problems, Mair said.

"These drugs specifically target mitochondrial dysfunction and upstream mechanisms that lead to this dysfunction," Mair told Live Science in an email.

Similarly, the Cardinal Heart 2.0 experiment will use tiny, 3D clumps of heart tissue, known as heart organoids, to test whether already-approved drugs can protect heart cells from the stress of microgravity. The organoids will be treated prior to Dragon's launch, with the goal of preventing the negative effects of microgravity from setting in, Dilip Thomas, a postdoctoral researcher at the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute who's involved in Cardinal Heart 2.0, said at the news conference. These drugs include a statin and an anti-hypertensive drug used for heart failure, Thomas told Live Science in an email.

The organoids, grown from stem cells, are tiny models of full-size hearts that mimic key features of the organ's structure and function. They contain cardiomyocytes, as well as cells that provide physical scaffolding for heart muscles (cardiac fibroblasts), and ones that line blood vessels (endothelial cells).

The Dragon spacecraft is set to launch at 8:30 p.m. EDT Tuesday (0030 GMT Wednesday) from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Here's how to watch it live.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.