Beetles suck water into their butts to stay hydrated, and now scientists know how

Instead of drinking water through their mouths, beetles opt for a different approach by using their butts.

Whenever beetles get thirsty, all they need to do is take a sip of water — through their butts.

This unconventional method of quenching their thirst is a way for the insects to stay hydrated, since they can go their entire lives without actually drinking water through their mouths, according to a study published March 21 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

While this derrière-drinking behavior was known to scientists, the mechanisms behind it were unclear. Now, a new investigation by researchers from Denmark and Scotland reveals that the insects can pull in moisture from the air through their rectums and convert it into a fluid, which is then absorbed into their bodies, according to a statement.

This weird trick is especially beneficial when living in an extremely dry environment.

Related: After being swallowed alive, water beetle stages 'backdoor' escape from frog's gut

"A beetle can go through an entire life cycle without drinking liquid water," study co-author Kenneth Veland Halberg, an associate professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Copenhagen, said in a statement. "This is because of their modified rectum and closely applied kidneys, which together make a multi-organ system that is highly specialized in extracting water from the food that they eat and from the air around them."

For the study, scientists scooped up poop samples from beetles such as grain weevils (Sitophilus granarius) and red flour beetles (Tribolium castaneum) and under a microscope noticed that their excrement was "completely dry and without any trace of water," Halberg said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

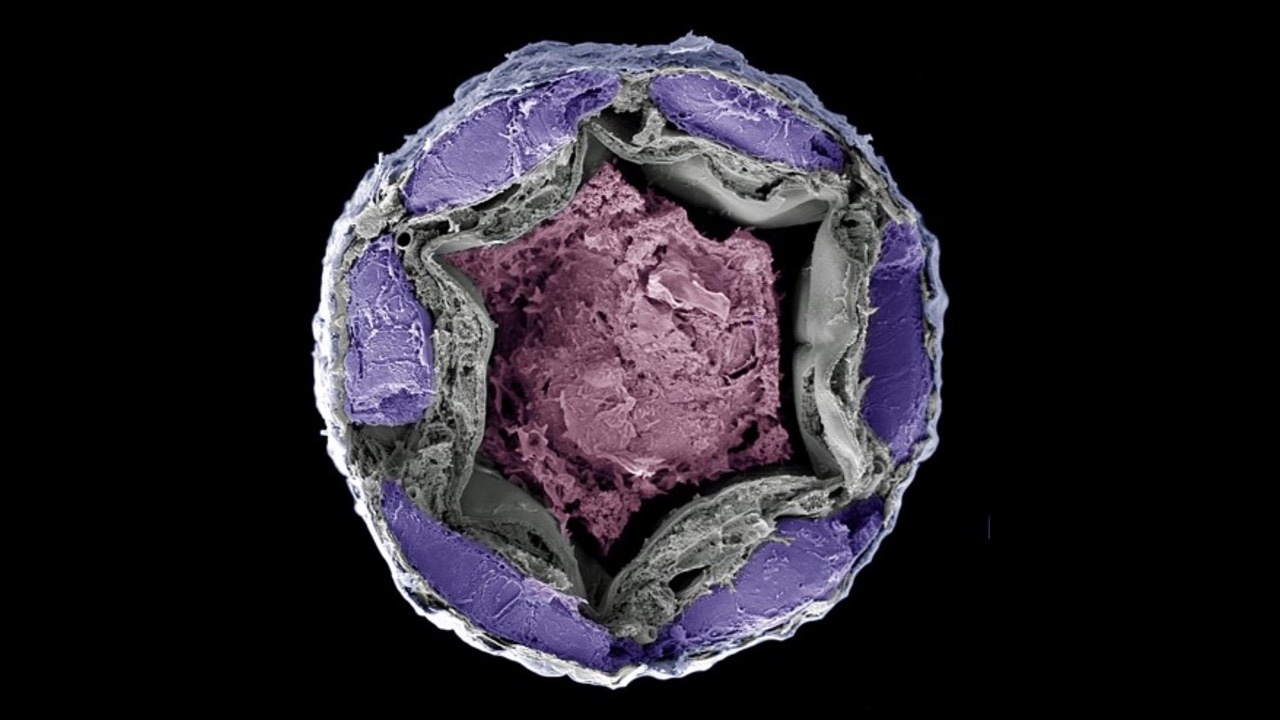

This is due to a gene known as NHA1 "that is expressed 60 times more in the beetle's rectum compared to the rest of the animal," according to the statement. This anomaly resulted in "a unique group of cells known as leptophragmata cells," which the researchers determined "play a crucial role when the beetle absorbs water through its rear end."

"Leptophragmata cells are tiny cells situated like windows between the beetle's kidneys and the insect circulatory system, or blood," Halberg said. "As the beetle's kidneys encircle its hindgut, the leptophragmata cells function by pumping salts into the kidneys so that they are able to harvest water from moist air through their rectums and from here into their bodies. The gene we have discovered is essential to this process, which is new knowledge for us."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.