Bering Land Bridge formed much later than originally thought, study suggests

The formation of the Bering Land Bridge connecting Asia to North America occurred much later than experts thought.

The Bering Land Bridge, a stretch of land that once connected Asia with North America, came into existence much later than experts previously thought, but humans likely crossed not long after it formed, according to a new study.

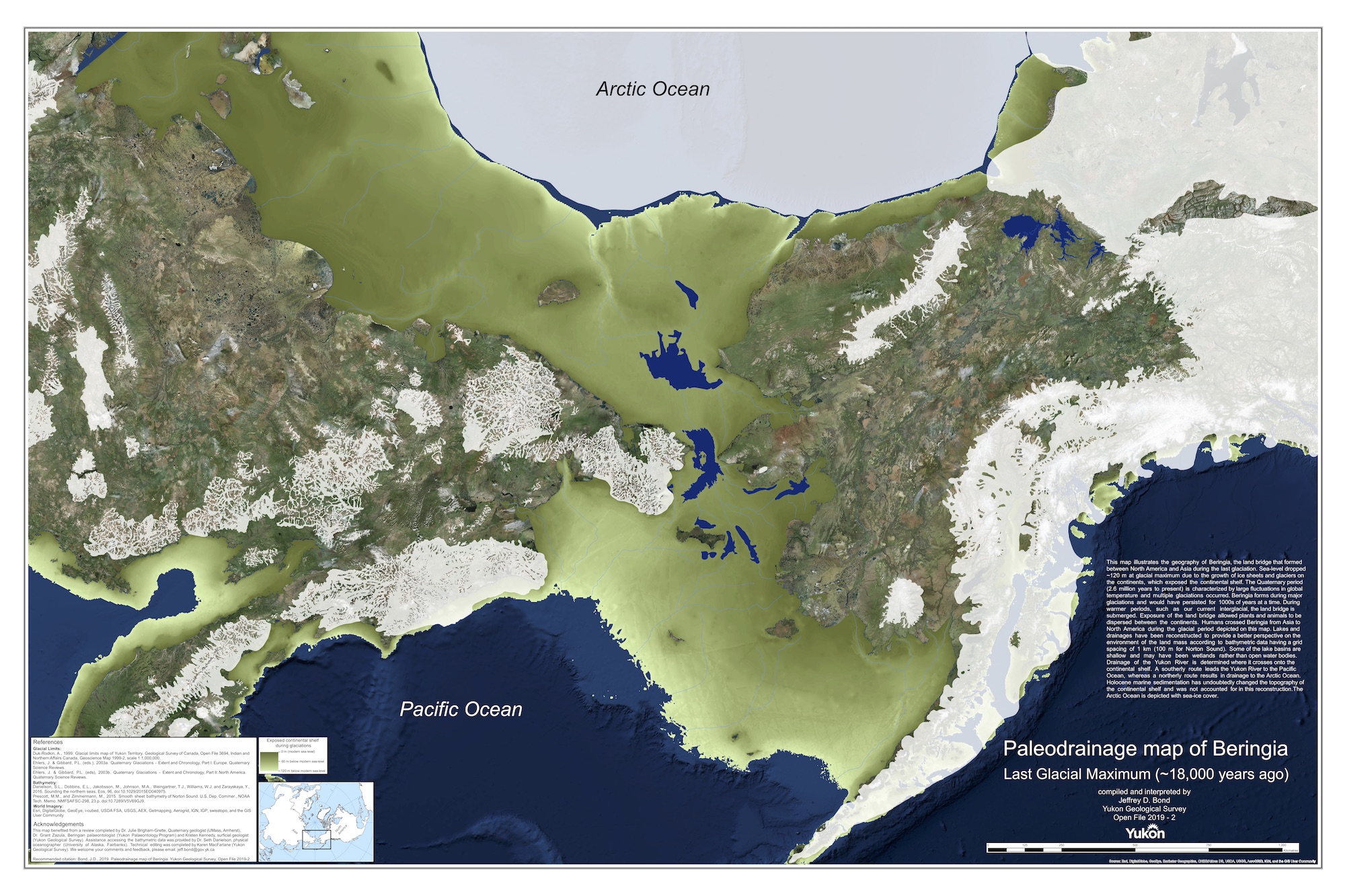

Researchers reconstructed the sea level history of the Bering Land Bridge from 46,000 years ago and found that it didn't emerge until around 35,700 years ago, which is less than 10,000 years before the last ice age, also known as the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), according to the study published Dec. 27 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The land bridge existed toward the end of the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), a time filled with cold glacial and warm interglacial periods. The land bridge's dates are still debated, with some scientists saying it existed from about 30,000 to 16,000 years ago.

The new findings suggest that the growth of the ice sheets, which led to a subsequent drop in sea levels, occurred later in the glacial cycle, with the Bering Strait being open and flooded from at least 46,000 to 35,700 years ago, according to the study.

The land bridge opened up before the LGM (26,500 to 19,000 years ago), when gigantic ice sheets covered large swaths of North America. On average, global sea levels were about 425 feet (130 meters) lower during the LGM than they are today, which helped keep the Bering Land Bridge open for migrating humans and ice age giants, such as woolly mammoths, horses and cave bears. The new finding concludes that "ice volume increased rapidly into the LGM," the researchers wrote in the study.

"It means that more than 50% of the global ice volume at the Last Glacial Maximum grew after 46,000 years ago," study co-author Tamara Pico, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said in a statement. "This is important for understanding the feedbacks between climate and ice sheets, because it implies that there was a substantial delay in the development of ice sheets after global temperatures dropped."

People likely started crossing the Bering Land Bridge as soon as it enabled passage between the continents, Pico said. "Our results shorten the time window between the opening of the Bering Land Bridge and the arrival of humans in the Americas," the researchers wrote in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As Earth warmed and its ice sheets began melting, the bridge became inundated around 11,000 to 13,000 years ago as it disappeared under the Bering Strait, the researchers said.

For the study, Pico and her colleagues analyzed the ratios of nitrogen isotopes collected from sediments on the seafloor of the western Arctic Ocean to better understand when the Bering Strait was flooded with water flowing in from the Pacific Ocean. (Isotopes are variations of elements that have different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei.)

"The exciting thing to me is that this provides a completely independent constraint on global sea level during this time period," Pico said. "Some of the ice sheet histories that have been proposed differ by quite a lot, and we were able to look at what the predicted sea level would be at the Bering Strait and see which ones are consistent with the nitrogen data."

For decades, experts have been debating exactly how long the Bering Land Bridge existed, and this study adds a new layer to what has become a controversial topic on when the first humans arrived in the New World.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.