Landsat satellites: 12 amazing images of Earth from space

These amazing images of Earth from space provide a unique perspective of our planet.

The following amazing images of Earth from space were snapped by satellites in the Landsat project, a joint venture between NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey. The project is the longest continuous space-based record of Earth in existence.

A total of eight Landsat satellites have been launched into space since 1972, with a ninth set to launch in September. In that time, the satellites have captured more than 9 million images of the planet's surface, which have been used in more than 18,000 scientific papers, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

Related: In photos: Jaw-dropping images reveal science is amazing

Where the dunes end

This image, captured by Landsat 8 on Nov. 13, 2019, shows the striking color contrast between the Namib Sand Sea, the world's only coastal desert, covering more than 10,000 square miles (26,000 square kilometers), and the rocky mountains of the Namib-Naukluft Park, both in Namibia. The sand appears a reddish-orange color due to the presence of iron oxide. The Kuiseb River, which is prone to flooding, stops the sand from spilling over into the mountains, according to the Earth Observatory.

Related: Photos: Stunning shots of the natural world and wildlife

Yukon-Kuskokwim in colorful transition

This image of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, where the Yukon River spills into the Bering Sea in Alaska, was taken on May 19, 2021, by Landsat 8. The colors on land have been enhanced in this photo: Green highlights the area of live vegetation; yellow is bare ground; and light brown is dead vegetation. "The Yukon Delta is an exceptionally vivid landscape, whether viewed from the ground, from the air or from low-Earth orbit," Gerald Frost, a scientist at ABR, Inc — Environmental Research and Services in Alaska, told the Earth Observatory.

From Russia with questions

Landsat 8 captured this photo of bizarre ripples in the hills surrounding the Markha River in northern Russia on Oct. 29, 2020. The alternating light and dark stripes are visible throughout the year but are more pronounced in winter. Scientists aren't exactly sure why the pattern exists. It could have emerged because of the constant freezing and melting of permafrost or due to some kind of unique erosion from rainfall or snowmelt, but NASA remains unsure, Live Science previously reported.

Winds trigger pond growth

This striking image of the Atchafalaya Delta in Louisiana was taken by Landsat 8 on Dec. 1, 2016. It is a false-color image, meaning that the colors have been altered, which "emphasizes the difference between land and water, while allowing viewers to observe waterborne sediment," according to the Earth Observatory. It is one of 10,000 Landsat images of the region taken between 1982 and 2016, which were used in a study published in Geophysical Research Letters that looked at the role wind plays in pond expansion on the Mississippi River Delta Plain.

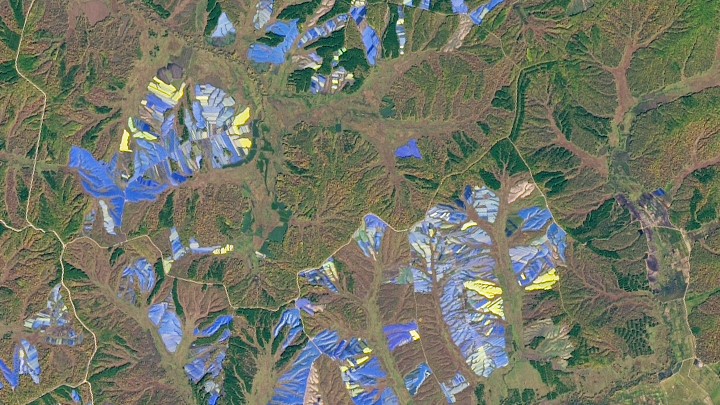

Ginseng farms in northern China

On Sept. 25, 2017, Landsat 8 captured this image of blue, purple and yellow structures covering large areas of farmland in Heilongjiang province in northeastern China. The structures are plastic shade covers used to grow ginseng — a slow-growing root plant that looks very similar to ginger but can't survive in direct sunlight. In many Asian countries, ginseng is believed to have a wide range of medicinal properties, and farming the plant has become a multi-billion dollar business, according to the Earth Observatory.

Painting Pennsylvania hills

This impressive image combines a satellite image of folded mountains — warped mountains formed at the boundary between two tectonic plates — in central Pennsylvania, taken by Landsat 8 on Nov. 9, 2020, with a digital elevation model to highlight the topography of the area. The mountains are part of a unique geological region of the Appalachian Mountains, known as the Valley and Ridge province, which stretches from New York to Alabama. As well as showing off the unusual shapes of the mountains, this natural-color image also reveals the autumnal palette of colors created as leaves turn red and begin to fall from deciduous trees, according to the Earth Observatory.

Jason and the Bloomonauts

This stunning natural-color image of an algal bloom surrounding the western Jason Islands, an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean, was taken by Landsat 8 on Oct. 18, 2020. The milky blue swirls are caused by the rapid growth of photosynthetic algae, which thrive in the nutrient-rich waters that have been enriched by the Malvinas Current — a spin-off of the Circumpolar Current of the Southern Ocean, which draws up nutrients from the deep ocean, according to the Earth Observatory.

Lake Natron

This striking aerial photo of the blood-red Lake Natron in Tanzania was taken by Landsat 8 on March 6, 2017. Lake Natron is an alkaline lake. The dramatic color is fueled by molten mixtures of sodium carbonate and calcium carbonate salts from nearby volcanoes that enter the water via hot springs. With temperatures averaging 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius) and less than 19.7 inches (500 millimeters) of rainfall a year, it is one of the harshest environments on Earth, according to the Earth Observatory.

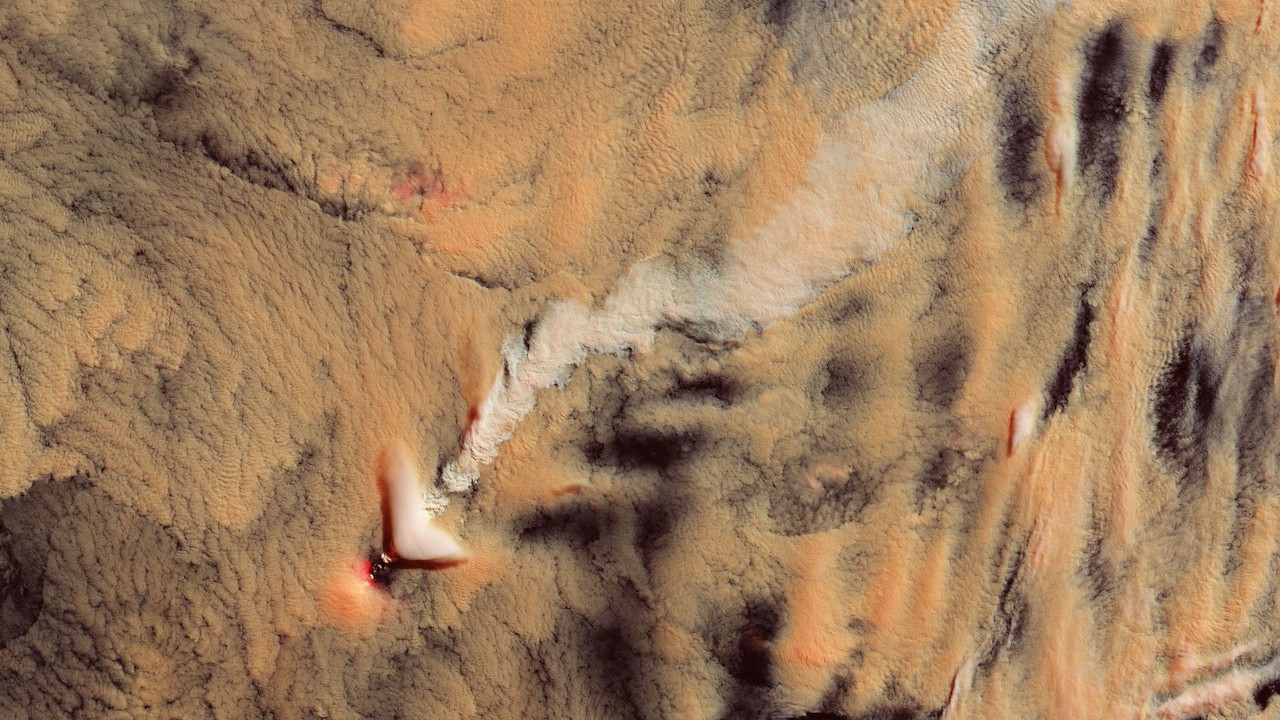

Volcano tracking in the South Sandwich Islands

On 7 Nov. 2021 the Landsat 8 obtained this image of Mount Michael - a 2,765 foot (843 meter) volcano located in the South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic, according to the Smithsonian Institution. Usually, satellite imagery of this stratovolcano (a steep-sloped and cone-shaped volcano) is masked by cloud coverage, according to NASA’s Earth Observatory.

However, in this image, a trail to Mount Michael is revealed by white steam produced by volcanic gas and particles interacting with passing clouds. The inclusion of the volcanic particles makes the passing clouds appear brighter due to the creation of more cloud droplets, according to NASA. Around the summit of the volcano is a triangular wave cloud which is created when mountains and volcanoes break the path of passing clouds, in the same way that moving your finger through water creates waves and ripples.

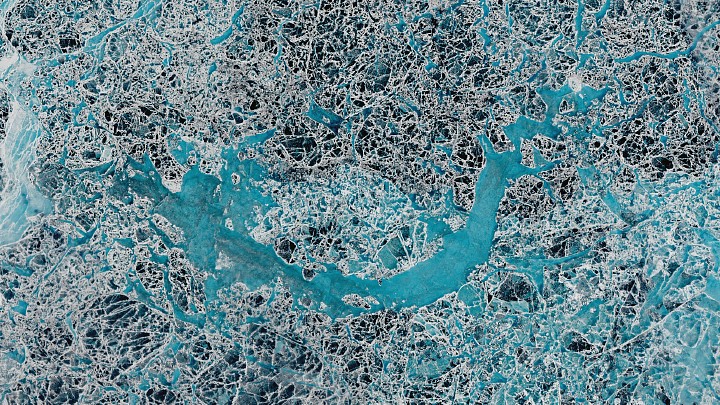

Icy art in the Sannikov Strait

This fascinating photo of the Sannikov Strait — a body of water sandwiched between the New Siberian Islands north of mainland Russia — was taken by Landsat 8 on June 5, 2016. The strait connects the Laptev Sea to the west with the Siberian Sea to the east; the strait remains covered in ice for the majority of the year, Live Science previously reported. This photo shows the ice sheet breaking apart during the summer melt and creating a picturesque panorama of icy puzzle pieces.

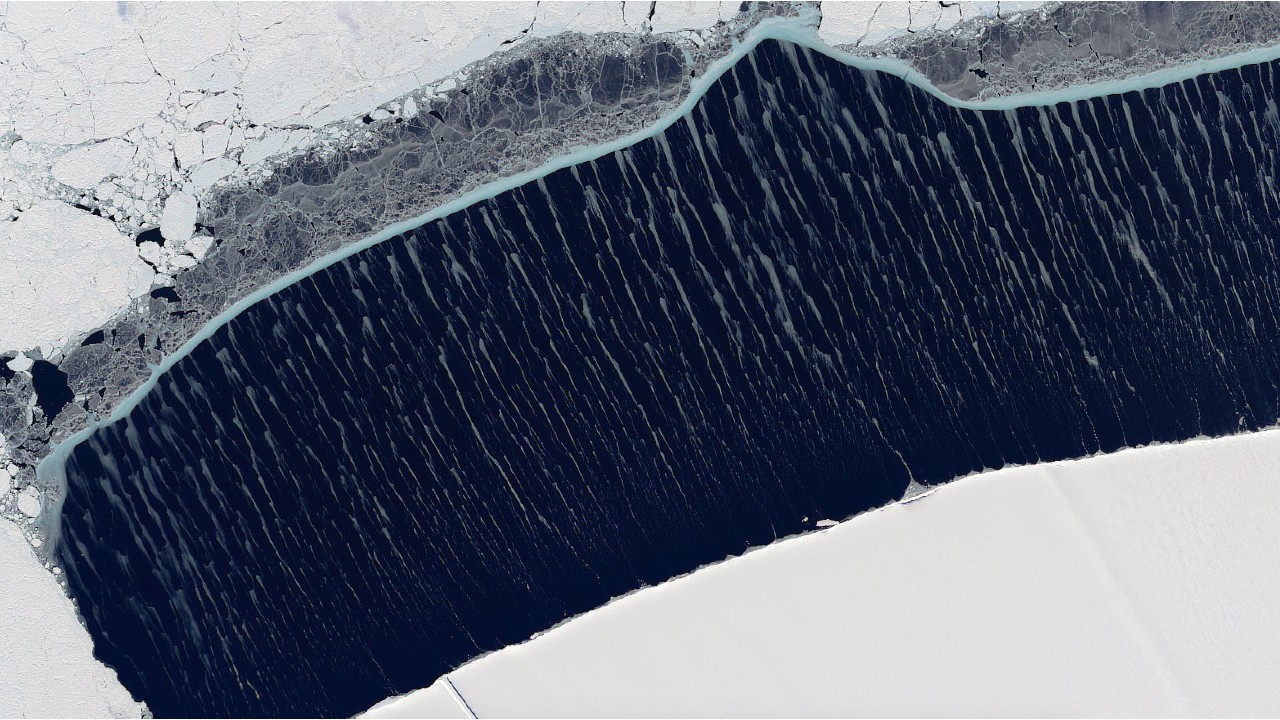

Windswept ice shelf in Weddell Sea

Sea ice typically gathers around the perimeter of an ice shelf, such as Antarctica’s Ronne Ice Shelf seen in this image. However, on 20 Nov 2021, Landsat 8 snapped this shot of a different sea ice type floating in a wide strip of water in the Weddell Sea created by strong winds, according to NASA’s Earth Observatory.

Between the thick Ronne Ice Shelf in the lower right corner of the image and the multi-layered sea ice populating the top of the image are sharp ribbons of nilas ice. This needle-like sea ice is made up of young ice crystals called frazil ice. Frazil ice eventually grows into nilas which are no more than around 4 inches (10 centimetres) thick.

Where batteries begin

This colorful array of cuboids found in the Salar de Atacama — a salt flat surrounded by mountains in Chile — is actually the world's largest lithium plant, photographed by Landsat 8 on Nov. 4, 2018. Lithium is the main component of batteries needed to power our cars, cellphones, laptops and other rechargeable gadgets.

This plant pumps lithium-rich brine from below the surface and diverts it into evaporation pools, where the sun evaporates the water away, leaving pure lithium. The different colors are a result of the varying stages of the evaporating process, according to the Earth Observatory.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.