This primeval worm may be the ancestor of all animals

Like humans, it had a butt, a head and two symmetrical sides. It's practically family.

Humans, it's been said, are like donuts. They have an opening at each end, and a single continuous hole running through their middle. (Note: This theory has yet to appear in a peer-reviewed journal.)

It's a crude simplification of our species, sure, but look far enough back on the animal family tree and you'll find an ancestor organism that's little more than a digestive tract with some meat wrapped around it. Limbless and hungry like a sentient macaroni, this ancient creepy-crawler was the first bilaterian — an organism with two symmetrical sides, a distinct front and back end, and a continuous gut connecting them.

While bilaterians run rampant today (insects, humans and most other animals among them), the identity of that progenitor organism has long eluded discovery. Now, researchers believe they've found it in the fossil record for the first time.

In a study published March 23 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of scientists analyzed a chunk of rock containing an ancient undersea burrow found deep below Australia. They found several fossil organisms preserved near the burrows, each creature about the size and shape of a grain of rice and dating to roughly 555 million years ago.

Related: This 500-million-year-old 'social network' may have helped animals clone themselves

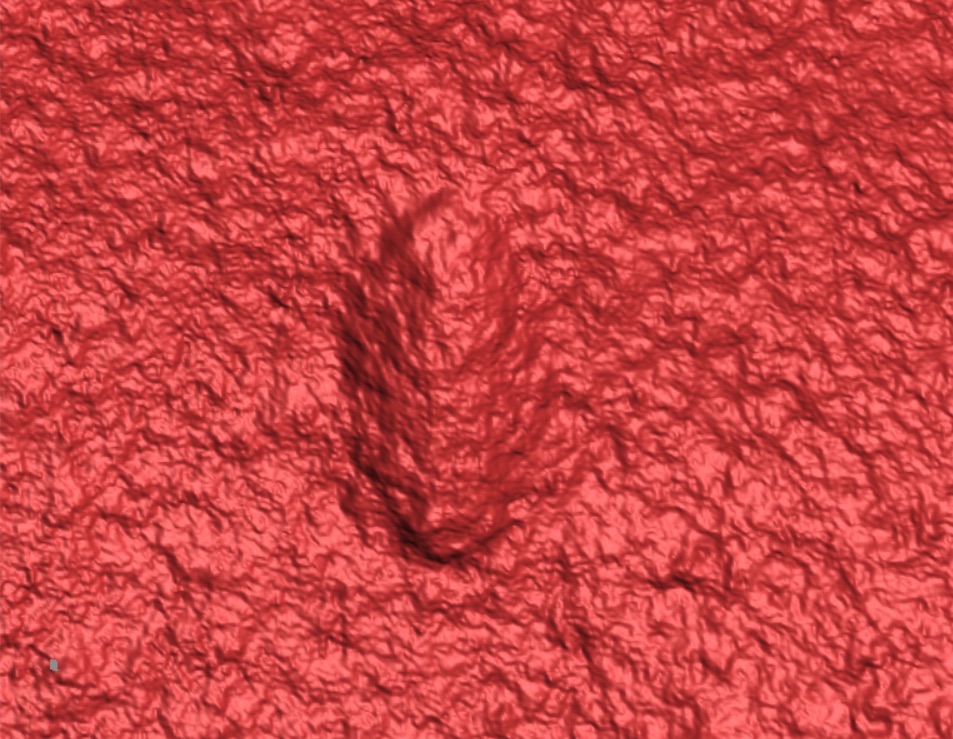

The burrows were clearly made by wriggling creatures with distinct front and back sides, but to get a more detailed picture of those ancient burrowers the researchers analyzed the fossils with a 3D laser scanner. They found that the tiny animals not only had a clear head and tail, but also had a bilaterally symmetrical body and faintly grooved musculature, similar to a worm. The researchers named this worm-like creature Ikaria wariootia, and dubbed it the oldest known example of a bilaterian — aka, the oldest shared ancestor of all living animals.

"Burrows of Ikaria occur lower than anything else," study co-author Mary Droser, a professor of geology at University of California, Riverside, said in a statement. "It’s the oldest fossil we get with this type of complexity."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ikaria wariootia lived during the Ediacaran period (571 million to 539 million years ago), when the first non-microscopic multicellular creatures emerged. At the time, the world was chiefly populated by amorphous undersea blobs (see, for example, the shape-shifting, bottom-feeding rangeomorphs). Most Ediacaran animals died in a mass extinction event, leaving no links to modern animals. Ikaria wariootia, however, is an exception — trace fossils of their burrows persist into the Cambrian period (541 million to 485.4 million years ago), suggesting they survived long enough to evolve bilaterian descendants, the researchers wrote.

In other words, perhaps you can thank this ancient rice-shaped worm for making you into a donut.

- Image gallery: Bizarre Cambrian creature

- Photos: 508 million-year-old bristly worm looked like a kitchen brush

- Photos: Ancient marine critter had 50 legs, 2 large claws

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.