Physicists keep trying to break the rules of gravity but this supermassive black hole just said 'no'

This supermassive black hole says "listen to Albert."

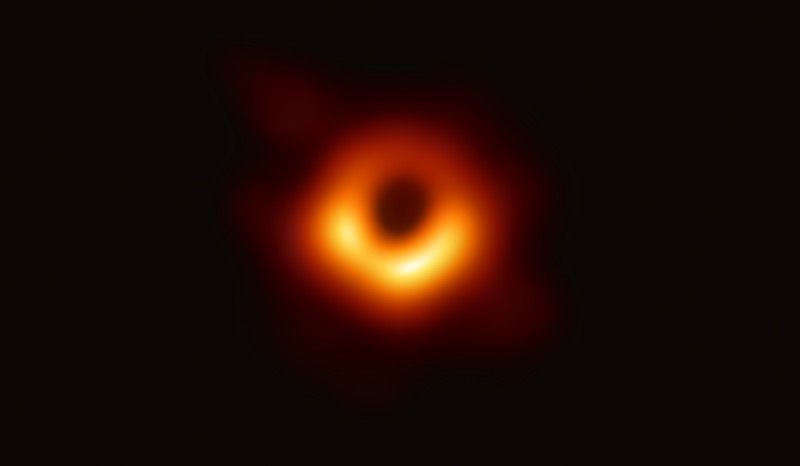

A new test of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity has proved the iconic physicist right again — this time by re-analyzing the famous first-ever picture of a black hole , which was released in April 2019.

That image of the supermassive black hole at the center of galaxy M87 was the first direct observation of a black hole's shadow — the imprint of the event horizon, a sphere around the black hole's singularity from which no light can escape. Einstein's theory predicts the size of the event horizon based on the mass of the black hole; and in April 2019, it was already clear that the shadow fits general relativity's prediction pretty well.

But now, using a new technique to analyze the image, the researchers who made the picture showed just how well the shadow fits the theory. The answer: 500 times better than any test of relativity done in our solar system. That result, in turn, puts tighter limits on any theory that would seek to reconcile general relativity, which describes the behavior of massive celestial objects, with quantum mechanics, which predicts the behavior of very small things.

General relativity's great accomplishment was to describe how gravity operates in the universe: how it pulls objects toward each other; how it warps space-time; and how it forms black holes. To test general relativity, scientists use the theory to predict how gravity will act in a certain situation. Then, they observe what actually happens. If the prediction matches the observation, general relativity has passed its test.

But no test is perfect. Watch how the sun's gravity tugs Mercury along its orbit, and you can measure general relativity in action. But telescopes can't measure the movement of Mercury down to the nanometer. And other forces — the tug of Jupiter's gravity, and Earth's gravity and the force solar wind, to name just a few — impact Mercury's movement in ways that are difficult to separate from the effects of relativity. So the result of every test is an approximation and Einstein's theory is only proven more or less.

Related: 8 ways you can see Einstein's Theory of Relativity in real life

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The size of that uncertainty — the "more or less" factor — is important. When scientists test general relativity over and over, they are putting constraints on Einstein's idea. The reason this work is important is that even though general relativity keeps passing tests, physicists do expect it to eventually fail.

General relativity must be incomplete, physicists believe, because it contradicts quantum mechanics. Physicists believe that discrepancy signals the presence in our universe of some larger, all-encompassing mechanism describing both gravity and the quantum world that they have yet to uncover. Looking for cracks in relativity, they hope, might turn up clues to help them find that complete theory."We expect a complete theory of gravity to be different from general relativity, but there are many ways one can modify it," University of Arizona astrophysicist Dimitrios Psaltis said in a statement. Psaltis is lead author of a paper published Oct. 1 in the journal Physical Review Letters describing this new test, and is part of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) team, responsible for imaging the M87 black hole's shadow.

In this new test, Psaltis and colleagues used a computer to generate artificial images of the M87 black hole based on a modified version of gravity, where the force of gravity is weaker or stronger at the event horizon. With that weakened-gravity scenario, they asked,how large or small would that black hole's event horizon be? What about with stronger gravity? Then, they checked how many of those possible modifications produced event horizons with sizes that matched that of the image EHT actually captured of M87. Some did, their slight variances from general relativity's predictions much too small to show up in the admittedly fuzzy snap of the black hole. But the vast majority did not.

Related: The 12 strangest objects in the universe

"Using the gauge we developed, we showed that the measured size of the black hole shadow in M87 tightens the wiggle room for modifications to Einstein's theory of general relativity by almost a factor of 500, compared to previous tests in the solar system," University of Arizona astrophysicist Feryal Özel, another study co-author and EHT scientist, said in the statement.

Most alternative ways that gravity might work that they considered — theories that violate Einstein's general relativity — don't fit within this newly narrowed wiggle room.

In the future, the EHT researchers said, they might be able to tighten that wiggle room even further.

The EHT is a network of radio telescopes all over the world that work together to produce the sharpest possible images of supermassive black holes — objects that, while large, are much too small and dim for any one telescope to resolve on its own. So far, the EHT has just published one image of one black hole, in M87. But there's another, smaller black hole in our own neighborhood that the collaboration should be able to image: Sagittarius A*, the supermassive at the center of the Milky Way.

As the EHT has trained its army of radio telescopes on this more nearby target, they've refined their theoretical technique and added new telescopes to the collaboration. The next image they produce, they say, should constrain general relativity even further.

Or maybe they'll see something Einstein didn't predict at all.

Originally published on Live Science.