Thousands of Earthlike 'blanets' might circle the Milky Way's central black hole

A new, strange sort of world might orbit the giant black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

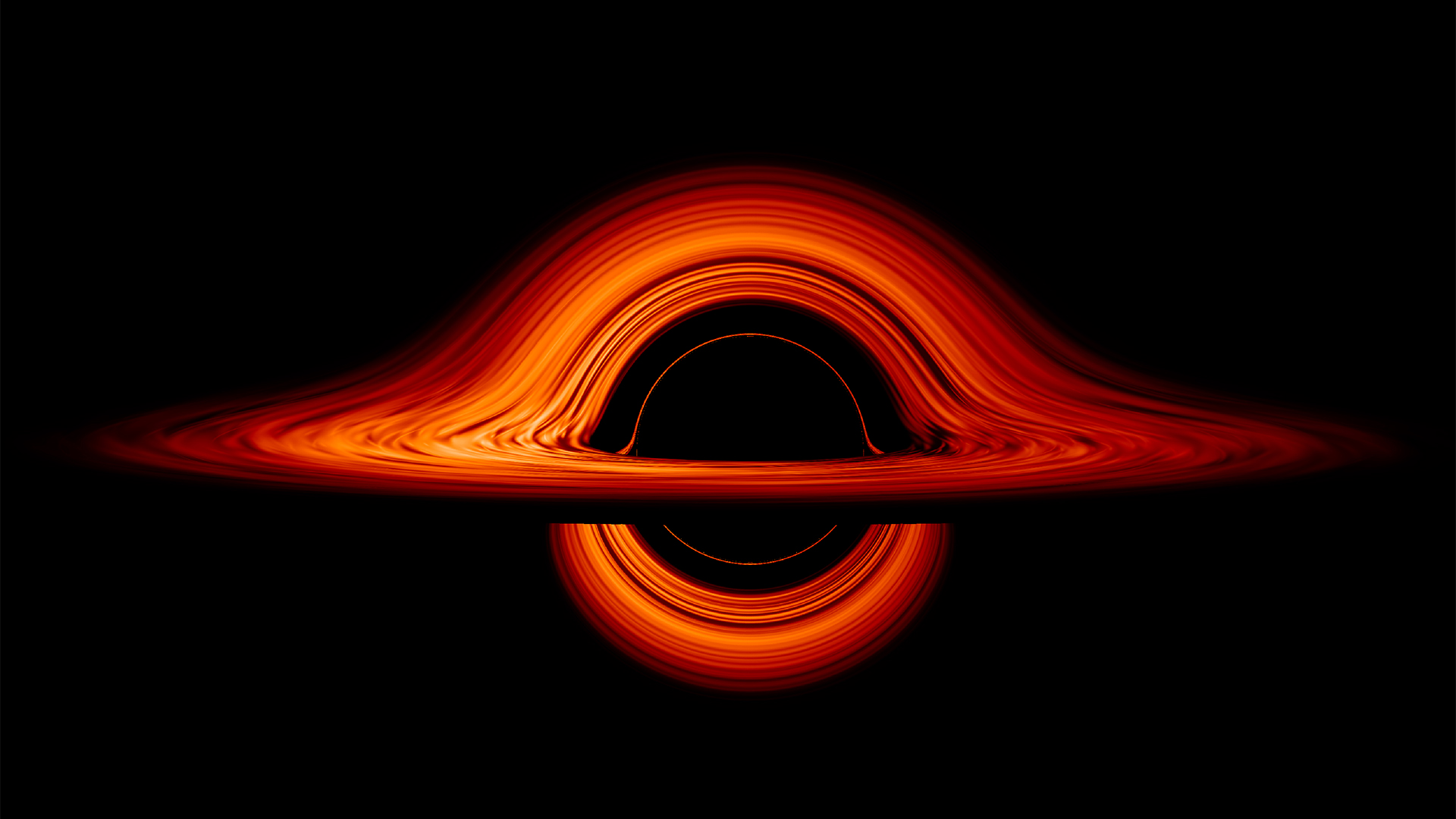

Supermassive black holes dot our universe, monstrous gravity wells that bind galaxies together and wreath themselves in whirling cocoons of dust that emit bright X-ray beams. Sometimes, bright columns of matter burst up from their poles, forming jets visible across space. And now some scientists suspect these gravitational monsters might host blanets — tens of thousands of them.

Nope, that's not a typo: Scientists suggest calling these black hole planets by the name "blanets." Such blanets would form from the clouds of whirling dust that circle black holes. And they wouldn't be too different from planets that orbit normal stars. Some would be hard and rocky, like Earth, though likely as much as 10 times larger. Some would be gas giants, like our solar system's Neptune. They'd almost certainly be invisible to us, hidden in the disk of matter that birthed them and dwarfed by their supermassive parents. But in a pair of papers published in The Astrophysical Journal in November 2019 and on arXiv in July 2020, respectively, a team of researchers laid out the case that these black hole planets must exist.

Related: The biggest black hole findings

Not every supermassive black hole (SMBH) would host blanets. Morphing into a hard ball of matter is trickier around a black hole than in the protoplanetary disk around a young star. The swirling dust and gas around an SMBH is far less dense, and the corona of infalling matter at the edge of its event horizon might be so hot and bright that ice can't form anywhere in the whirling disk.

And ice is one of the key ingredients for planet formation.

Ice-covered dust particles tend to clump together when they collide — think of how two ice cubes might stick together when smashed into each other, versus two pebbles that definitely do not, said lead author Keiichi Wada, an astrophysicist as Kagoshima University in Japan. Over time, those clumps grow and develop enough gravity to pull in even more dust. Clumps that grow big enough then form rocky planets.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Similarly, without frozen water or carbon dioxide ("dry ice"), it's very hard to build a blanet, Wada told Live Science. Some black holes have "snow lines" in their disks of orbiting matter, regions beyond which space is cool enough for ice to form, the researchers found.

"Beyond the line, the dust particles are covered with [ice]," Wada told Live Science. "As a result, they are easily stuck together when they collide."

Beyond the snow line, rocky blanets could form from progressively larger clumps in about 10 million years. If these rocky proto-blanets attracted enough gas, they'd eventually form gas giants. But none of that can happen without a thin film of ice on the dust grains. So dimmer, cooler SMBHs (like the one at the center of the Milky Way) are the most likely homes for these strange planets.

In a sense, Wada said, blanets aren’t especially surprising. Protoplanetary disks are similar to the swirls of matter around black holes. But no one had investigated whether planets could form around an SMBH before, "probably because researchers in the field of planet formation do not know much about active galactic nuclei, and vice versa," Wada said. (An "active galactic nucleus" is the region around a SMBH at the center of a galaxy.)

Related: 9 facts about black holes that will blow your mind

Wada and his co-authors are still working out the details of their blanet theory. In the 2020 paper, the team corrected and updated the model published in 2019. Their original blanet model, he said, was too "fluffy," forming big, low-density puffball planets. Their updated model produces denser, more realistic planets. And they refined their understanding of how the dust around a SMBH, where it is distributed much more diffusely than it is around a star, would behave as it clumped together in the thin gas environment of a SMBH disk, Wada said.

It's difficult to imagine what the surface of these blanets might look like, he said. Leave aside the strangeness of orbiting a supermassive black hole: The blanets themselves would orbit much farther from one another and from the black hole than Earth does from its siblings or the sun; a dozen light-years could separate a blanet from its host black hole, making them oddly solitary.

As of now, Wada said, there's no way to know whether life might exist on blanets. Would the strange ultraviolet light and X-ray radiation emitted from a black hole's corona allow alien beings to thrive in such a lonely portion of the cosmos? Are there blanet denizens looking up at the stars and wondering if they too are orbited by balls of rock and gas?

And do they call those star-planets "slanets"?

Originally published on Live Science.