Scientists spot flash of light from colliding black holes. But how?

Black holes aren't supposed to make flashes of light. It's right there in the name: black holes.

Even when they slam into each other, the massive objects are supposed to be invisible to astronomers' traditional instruments. But when scientists detected a black hole collision last year, they also spotted a weird flash from the crash.

On May 21, 2019, Earth's gravitational wave detectors caught the signal of a pair of massive objects colliding, sending ripples cascading through spacetime. Later, an observatory called the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) caught a blast of light. As scientists looked at the two signals, they realized both came from the same patch of sky, and researchers started wondering whether they had spotted the rare visible black hole collision.

"This detection is extremely exciting," Daniel Stern, coauthor of a new study on the discovery and an astrophysicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said in a NASA statement. "There's a lot we can learn about these two merging black holes and the environment they were in based on this signal that they sort of inadvertently created."

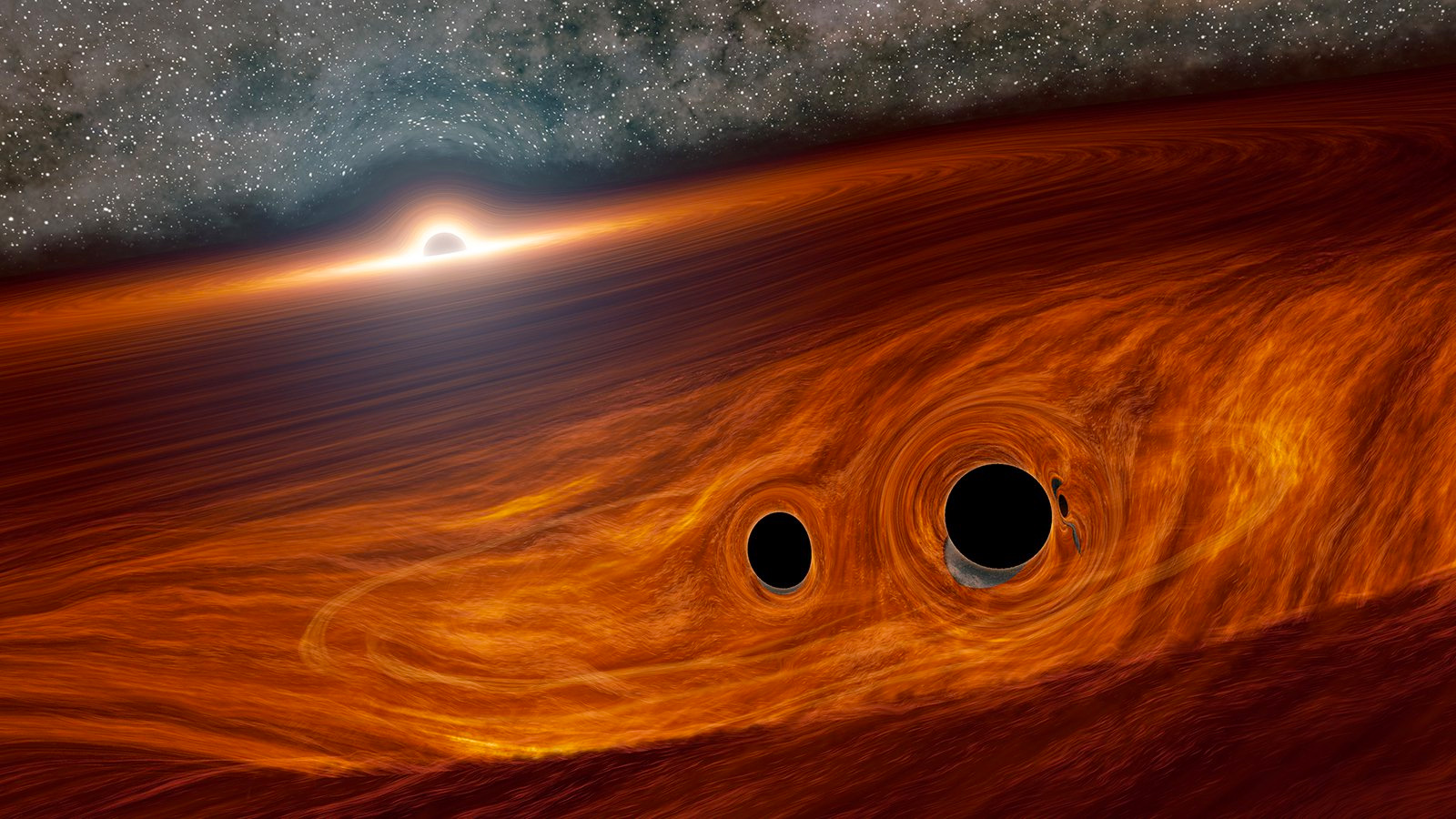

Here's what scientists think happened in this strange case. The two black holes that merged were locked in the disk surrounding a quasar, a supermassive black hole that shoots out blasts of energy.

"This supermassive black hole was burbling along for years before this more abrupt flare," Matthew Graham, an astronomer at Caltech and the project scientist for ZTF, said in a university statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That in and of itself isn't so strange, according to his colleague. "Supermassive black holes like this one have flares all the time," co-author Mansi Kasliwal, an astronomer at Caltech, said in the statement. "They are not quiet objects, but the timing, size and location of this flare was spectacular."

Scientists suspect, based on the pairing of gravitational waves and light, that the flare sprang from two small black holes merging within the accretion disk of the supermassive black hole. The supermassive black hole's incredibly strong gravity affects the smaller stuff in the disk, even other black holes.

"These objects swarm like angry bees around the monstrous queen bee at the center," co-author K. E. Saavik Ford of the City University of New York Graduate Center, the Borough of Manhattan Community College and the American Museum of Natural History, said in the statement. "They can briefly find gravitational partners and pair up but usually lose their partners quickly to the mad dance. But in a supermassive black hole's disk, the flowing gas converts the mosh pit of the swarm to a classical minuet, organizing the black holes so they can pair up."

The flash of light doesn't come from the merger itself, the scientists think. Instead, the force of the merger sends the now-a-little-larger black hole flying off, through the gas surrounding it in the supermassive black hole's accretion disk. The gas, in turn, produces the flare after a delay of days or weeks, the theory goes according to the statement. In the case of this event, scientists detected the flare about 34 days after the gravitational wave signal.

That's not a guarantee that this explanation fits what happened, the researchers said.

"The flare occurred on the right timescale, and in the right location, to be coincident with the gravitational-wave event," Graham said. "We conclude that the flare is likely the result of a black hole merger, but we cannot completely rule out other possibilities."

The results are described in a paper published on Thursday (June 26) in the journal Physical Review Letters.

- Eureka! Scientists photograph a black hole for the 1st time

- Why is the first-ever black hole photo an orange ring?

- No escape: dive into a black hole (infographic)

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.