Medieval Scot with strong jawbone wasn't a local

The bloke may have grown up in the Hebrides or Ireland.

A medieval man whose face was immortalized in a striking reconstruction isn't quite who we thought he was. The so-called Blair Atholl Man, who died at the age of 45 and was buried near Blair Atholl in the Scottish Highlands some 1,600 years ago, was not a local, researchers now say.

Instead, Blair Atholl Man likely spent his childhood on the western coast of Scotland, perhaps on one of the islands of the western Hebrides, such as Mull, Iona or Tiree, or maybe he grew up farther away, in Ireland, a chemical analysis of his remains revealed.

News of this man's journeys adds to a growing line of evidence that people traveled long distances in early medieval Scotland. Research at two other archeological sites — the villages of Lundin Links and Cramond on the eastern coast of Scotland — show "that these types of movements may have not been uncommon," study co-researcher Kate Britton, a professor of archaeological science and head of the Department of Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, told Live Science in an email.

It wasn't just men who were journeying to far-flung spots, either. "What is interesting is that at both those east-coast sites [Lundin Links and Cramond], our west-coasters were females, suggesting that both men and women — and perhaps for a variety of reasons — were making these journeys," Britton said.

Related: In photos: Medieval skeleton entangled in tree roots

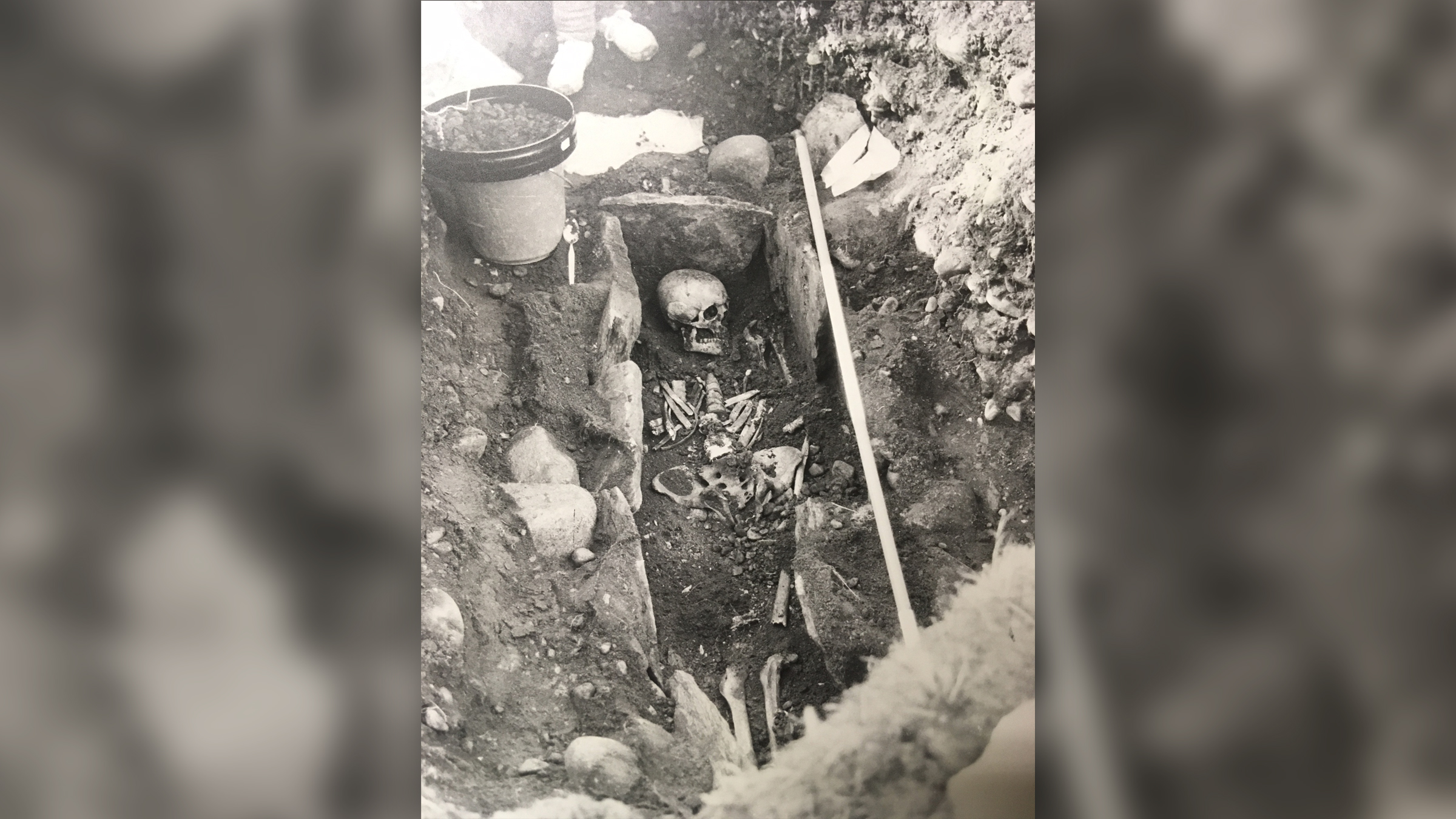

Blair Atholl Man's remains were found during construction work at a house in Bridge of Tilt, the community next to Blair Atholl, in 1985. After getting a call from the local police, Alison Reid, curator of archaeology at Perth Museum and Art Gallery, got to work, excavating the burial and the skeleton interred within it. Researchers dated his remains to between A.D. 400 and 600, and the public, intrigued by the medieval discovery, flocked to the Atholl Country Life Museum where a seasonal exhibit showcased his remains for years.

"After such an incredible discovery, the local community interest in Blair Atholl Man never waned," said study co-researcher Orsolya Czére, a teaching and research fellow in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen. The medieval man's popularity, along with advances made in archaeological sciences, prompted scientists to analyze isotopes (variations of elements) in Blair Atholl Man's bones and teeth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To investigate Blair Atoll Man's diet in the five to 10 years preceding his death, researchers extracted collagen, a protein found in bones and other tissues, from a rib fragment. By examining the collagen's carbon and nitrogen isotopic ratios, the researchers were able to infer what the man had eaten, as nutrients from the food he ate ended up in his bones. These isotopic ratios revealed that Blair Atholl Man had a "diet strikingly similar to what we've been seeing throughout early medieval Scotland," meaning he likely dined on pork, freshwater fish or even waterfowl, Czére told Live Science in an email.

The team also examined sulfur isotope ratios in the collagen, which can show both diet and residence along the coast, where sulfur can build up. Blair Atoll Man had elevated sulfur isotope ratios, indicating that "he spent the majority of his later life elsewhere, near a coastal location, and therefore may have been a relative newcomer to the area," Czére said.

Finally, a look at the strontium and oxygen isotopes in his tooth enamel (which forms during childhood) showed that Blair Atholl Man grew up around older rock formations than are present in central Scotland and that he lived in a place with a milder climate, such as Scotland's western coast.

However, much is unknown about the man, including whether he was a Pict, the Indigenous people who lived in what is now eastern and northeastern Scotland from ancient through medieval times. The Picts were fiercely independent and often in conflict with the encroaching Roman Empire, and may have developed their own written language about 1,700 years ago, Live Science previously reported. "What we can say is that Blair Atholl Man was born in a more remote geographical area that was not part of Pictland, yet he moved to this region and was buried according to funerary customs practiced by the Picts," Britton said.

Despite this unknown, the isotopic analyses revealed an unprecedented amount of biographical data about Blair Atholl Man. "Not only does this allow us to paint a picture of an individual who lived and died more than 1,500 years ago, but also to gain direct information on the early connections between cultures and communities across Scotland in the first millennium," Czére said.

The study, a collaboration with the University of Aberdeen, University of Reading, British Geological Survey, Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre, Guard Archaeology, and Perth Museum and Gallery, was published online on Sept. 24 in the Tayside and Fife Archaeological Journal.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.