The strange behavior of a star that dimmed, nearly disappeared, and then brightened back to its normal brilliance has left astronomers scratching their heads. Though other stars are known to dip in brightness on occasion, none are so dramatic or sustained, leading to speculation that this "blinking star" is an entirely new class of object.

The mysterious entity was spotted by the VISTA Variables in the Via Lactea (VVV) survey, which uses the VISTA telescope located atop Cerro Paranal mountain in Chile's Atacama Desert to look at nearly 1 billion stars using infrared light. After perusing the data, the team conducting the survey noticed that a single star lost 97% of its glare and then brightened again over the course of roughly six months.

"It's really quite unusual, that's not something that's been seen before," Philip Lucas, an astrophysicist at the University of Hertfordshire in the U.K., told Live Science.

Related: The 12 strangest objects in the universe

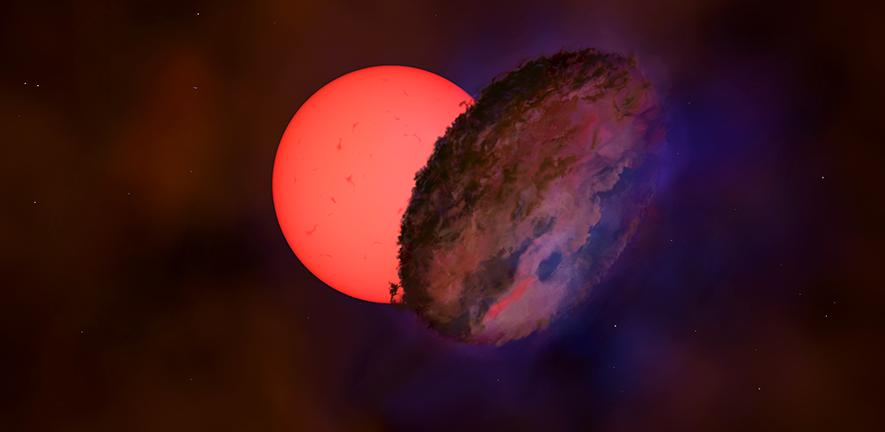

The researchers named the star VVV-WIT-8, where WIT stands for "What Is This?," he added. The object is an old, cool star about 100 times bigger than the sun, located 25,000 light-years away in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius, near the center of the Milky Way.

Some stars, called Cepheid variables, have regular fluctuations in brightness, but astronomers only saw the object dim once during the time the survey looked at it. (The survey has been running since 2010, and the dip occurred in 2012.) There are also stars like Epsilon Augirae, which is partially eclipsed by a large dust disk every 27 years, though it only loses 50% of its brightness when this happens.

The slow and lasting nature of the brightness dip suggested that something was passing in front of VVV-WIT-8, yet if it had a companion star orbiting it, telescopes should have picked up light from such a partner, Lucas said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Furthermore, whatever was causing the light loss seemed to be "really thick, almost as impenetrable to light as a solid object," he added.

Lucas and his colleagues still aren't sure what's going on. "There's a lot of possibilities and none of them quite work," Lucas said. Their findings appeared June 11 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

One possibility is that a random object happened to fly in front of the star, though the researchers think this is unlikely given the extremely small odds of such a chance alignment. Another is that VVV-WIT-8 has natural dips just as Cepheids do, though no Cepheid has ever been seen fluctuating to such an extreme degree.

The scientists' current favored explanation is that a large, dusty disk of material surrounds the star and occasionally passes in front of it, blocking its light. A similar occurrence happened during the recent dimming of the famous star Betelgeuse, which may have shot out a huge cloud of dust that obscured its brightness, as Live Science's sister site Space.com reported.

If a dust disk surrounds VVV-WIT-8, the disk might be orbiting on its own or it could surround some kind of dense companion — either a dim star or perhaps even a black hole, Lucas said. Black holes tend to shine brightly in X-rays, so the team is hoping to conduct further observations to see if they can spot any such energetic light coming from the region.

An orbiting object also means that telescopes might capture another dipping event sometime in the future. But data from the dip suggests that the two companions would be separated by at least 20 times the distance between Earth and the sun, Lucas said, implying that the obscuring entity could take hundreds of years to pass in front of the star again.

The idea that there is a companion with a thick disk is "probably the most complete description that can fit the data," Tabetha Boyajian, an astrophysicist at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge who was not involved in the work, told Live Science.

But additional research will be needed to pin down an explanation, she added. She noted that the last sentence of the team's paper ends with an exclamation point.

"When you end a paper with an exclamation point, it's a telltale sign that we need to do more work," she said.

In the meantime, the researchers have identified two more stars with similar light-loss behavior, meaning there might be other objects that can help them solve this mystery.

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.