Blood from cured coronavirus patients could help treat infection

On Thursday (Feb. 13), a Chinese senior health official called on people who had recovered from the new coronavirus to donate blood plasma, because it might contain valuable proteins that could be used to treat sick patients, according to The New York Times.

The call for plasma came after an announcement by the state-owned company, China National Biotec Group, that these antibodies helped treat 10 critically ill patients, reducing their inflammation within 12 to 24 hours, according to the Times.

But is this a good idea? The approach is a logical and promising way to treat critically ill coronavirus patients, experts told Live Science. But because coronavirus has a low mortality rate, bypassing the normal drug testing process doesn't necessarily make sense, and doctors should be on high alert for possible side effects, they said.

Related: Going Viral: 6 New Findings about Viruses

Antibodies are proteins that the immune system makes to fight invaders such as viruses, bacteria or other foreign substances. Antibodies are specific to each invader. However, it takes time for the body to ramp up its production of antibodies to a completely new invader. If that same virus or bacteria tries to invade again in the future, the body will remember and quickly produce an army of antibodies.

People who have recently recovered from COVID-19 still have antibodies to the coronavirus circulating in their blood. Injecting those antibodies into sick patients could theoretically help patients better fight the infection.

In other words, this treatment will transfer the immunity of a recovered patient to a sick patient, an approach that has been used previously in flu pandemics, Benjamin Cowling, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Hong Kong, told the Times.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I am glad to learn that under compassionate circumstances plasma from survivors is being tested," said Carol Shoshkes Reiss, a professor of biology and neural science at New York University who was not a part of the research. However, they will need to control for possible effects of the treatment, Reiss told Live Science in an email.

Under the Food and Drug Administration's "compassionate use" guidelines, experimental drugs can be given to people outside of clinical trials, typically in emergency situations. Though the FDA doesn't play a role in drug approval in China, a similar principle was likely at play; In this case, the people who were given the plasma were "critically ill," according to the Times.

Not everyone is convinced the rush to use blood plasma in patients makes sense.

"I think these theoretic[al] treatments are good ideas, but nothing about this virus or these infections makes me want to skip the normal process we use to make sure that a treatment is safe and effective before subjecting people to it," Dr. Eric Cioe-Peña, the director of global health at Northwell Health in New York who was not involved with the study, told Live Science in an email. "I think we should allow the scientific process to continue and attempt to study these proposed treatments before enacting them, especially in a virus that has such a low mortality."

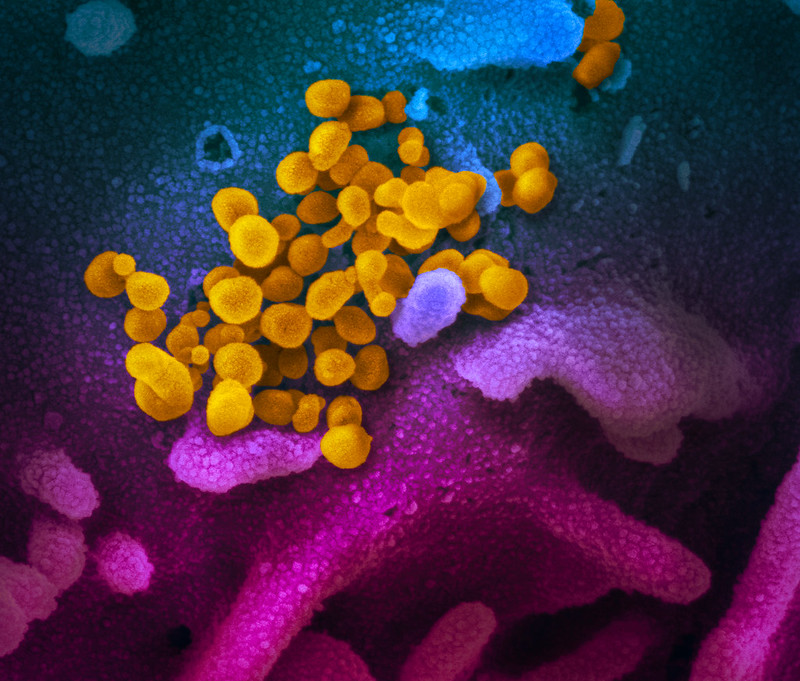

Plasma infusions are just one of many treatment options experts are considering to treat COVID-19, which has now sickened nearly 65,000 people and led to 1,384 deaths. Others include repurposing antivirals or looking for brand-new molecules that can block the binding of the virus into cells, Live Science previously reported.

- 27 devastating infectious diseases

- 10 deadly diseases that hopped across species

- Inside look: How viruses invade us

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.