European beads found in Alaska predate Columbus, controversial study claims

These glass beads might be from Venice.

Brilliantly blue beads from Europe unearthed by archaeologists in Arctic Alaska may predate Christopher Columbus' arrival in the New World, a new controversial study finds.

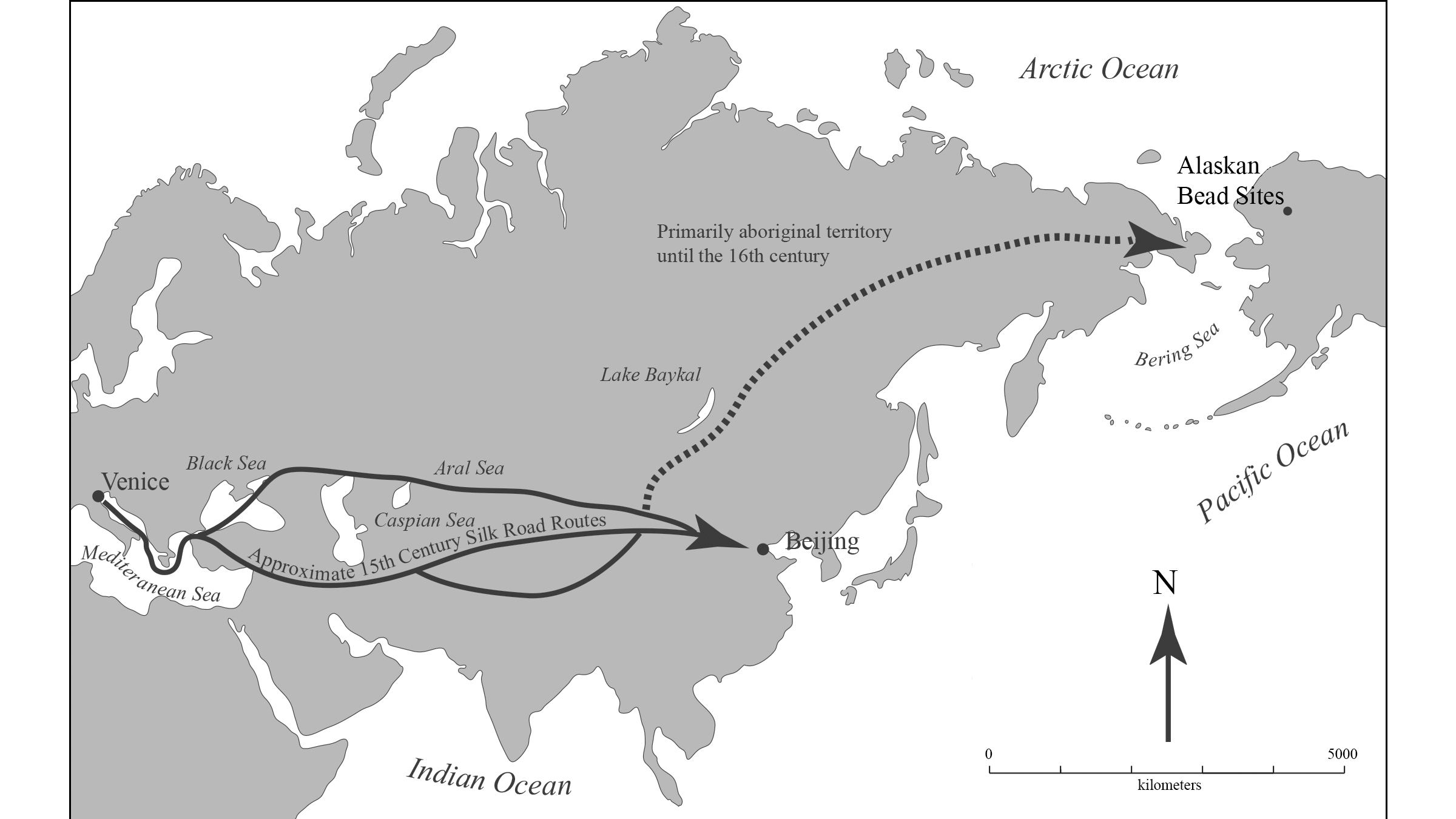

These blueberry-size beads were likely created in Venice during the 15th century and then traded eastward, enduring a 10,500-mile (17,000 kilometers) land-based journey east across Eurasia and then boated across the Bering Strait to what is now Alaska, according to the study, published online Jan. 20 in the journal American Antiquity.

However, other archaeologists dispute the findings, saying while these beads are old, they're not older than Columbus' 1492 voyage. "These beads cannot be pre-Columbian, because Europeans weren’t making beads of this type that early," said Elliot Blair, an assistant professor of anthropology at The University of Alabama, who was not involved in the study.

Instead, these glass beads likely date to the late-16th or early-17th century, which in itself is a "really cool story," Blair, who specializes in the dating and sourcing of early trade beads in the Americas, told Live Science. "Even with this later dating, an early 17th-century date for these beads is still much earlier than first documented contact between Alaska Natives and Europeans."

Related: In photos: Evidence of a legendary massacre in Alaska

Bright blue discovery

Vitus Bering, a Danish explorer serving in the Russian Navy, was thought to be the first modern European to make contact with Alaskan natives when he voyaged there in 1741. But the discovery of the blue beads indicates that people in Asia, possibly those living in the Aboriginal hinterlands or eastern Russia, may have known about Alaska much earlier.

An American archaeologist discovered the first of the blue glass beads in the 1960s, and since then a total of 10 have been unearthed at three Indigenous sites in Alaska's Arctic. Archaeologists have also found other artifacts at these sites, including copper bracelets and bangles, and iron pendants, as well as organic material: twine, animal bones and charcoal, which the researchers dated with radiocarbon.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The discovery of the twine, likely made from shrub willow bark, was key; it's wrapped around part of a blue-beaded bangle, meaning it could provide a date range of when the bangle was made. According to the radiocarbon-dating analysis, the twine likely dates to between 1397 and 1488, said study co-principal investigator Michael Kunz, an archaeologist with the University of Alaska Museum of the North in Fairbanks.

"We were astounded because that was before Columbus had ever even discovered the New World, by several decades," Kunz told Live Science.

After comparing the date ranges from the radiocarbon-dated artifacts — including the twine, two pieces of charcoal and four caribou bones — from the three sites, the researchers found that Indigenous people most likely used these beads between 1443 and 1488, but with potential dates spanning the 14th to 17th centuries.

If the mid-15th-century date is correct, the beads would be the oldest known European products brought to the New World and the oldest record of "drawn" beads, a bead type previously dated to the 16th century, Kunz said.

The team also had five of the beads examined with instrumental neutron activation analysis, a technique that bombards samples with radioactivity and then measures the radioactive decay through the gamma-rays that are emitted, which are unique to each element and can reveal the sample's chemical makeup. The results showed that "the Alaskan beads are made of soda glass, typical of fifteenth-century Venetian and later European manufacture," the researchers wrote in the study.

Perhaps, all of the blue beads came over in one shipment, so to speak, and were traded at a regional Indigenous trading center known as Sheshalik, by the mouth of the Noatak River and Bering Strait; after this initial trading interaction, the beads and their new owners likely dispersed across different parts of Alaska, Kunz said.

Related: Far Out: Ancient Egyptian jewelry came from space

"This research that we've done demonstrates that this type of beads — [known as] IIa40 early blue — existed long before they were thought to exist," Kunz said. "That's the bottom line. We're going against the grain. But we have good solid scientific evidence — radiocarbon dating, instrumental neutron activation analysis — that stands behind what we're saying."

Venetian glass?

Other archaeologists say the evidence doesn't add up.

The study "highlights the role of Indigenous exchange networks" of goods from Europe, "but, I also think this paper is a cautionary tale in sensationalizing a story beyond what the evidence supports," Blair said.

Historical and archaeological evidence of drawn beads "strongly indicates that they weren’t manufactured prior to about 1550 at the very earliest," Blair said. "I think it would take very strong evidence to push this date any earlier. The data the authors present doesn’t do this, and in fact, the authors’ own data is consistent with an early 17th-century date for these beads."

Blair is referring to the twine's radiocarbon dating; although the analysis shows the twine was likely created in the 15th century, it also shows that an early 17th-century date, though less likely, is possible.

In fact, a quick look at the study's radiocarbon date ranges shows that Indigenous Alaskans could have used the beads from 1570 to 1650, a period that fits with production records of European drawn beads, Blair said.

It's not even clear if the beads are from Venice, as the researchers suggest. "It is quite likely that the beads originated in France and not Venice, based on findings at a bead manufacturing site in Rouen," Karlis Karklins, an independent bead researcher and the editor of the Society of Bead Researchers, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "Early blue beads (IIa40) containing numerous bubbles were found in bead-making wasters at a site in Rouen, France, which is attributed to the early-17th century. … I do not know of such beads ever having been recovered from archaeological contexts in or around Venice."

There are chemical techniques that could ascertain whether the beads were made in Venice, Blair noted, and those could help solve the mystery of the beads' origin.

The researchers did agree on one thing, however — these beads are the oldest evidence on record of European products in Alaska.

"How they got to distant Alaska from Western Europe in the latter part of the 16th or early-17th century is quite a mystery in itself," Karklins said. "That really invites serious investigation."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.