Brain training probably won't reduce Alzheimer's risk — here's why

Science suggests "challenging the brain" won't prevent Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer's disease and related dementias affect an estimated 5.8 million people in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). By 2060, this figure is predicted to rise to 14 million.

Last month, the charity Alzheimer's Research UK launched an online "brain check" tool that suggests people could reduce their risk of dementia by making 12 lifestyle changes, including stopping smoking and cutting back on alcohol. One of the other suggested modifications is challenging the brain, for example by playing crossword puzzles, card games or board games, or by learning a new language.

"The check-in [tool] is based on the latest and strongest available evidence on 'modifiable' risk factors for dementia — the things we may be able to influence," Emma Taylor, an information officer for Alzheimer's Research UK, told Live Science in an email.

But can challenging the brain really help prevent Alzheimer’s disease?

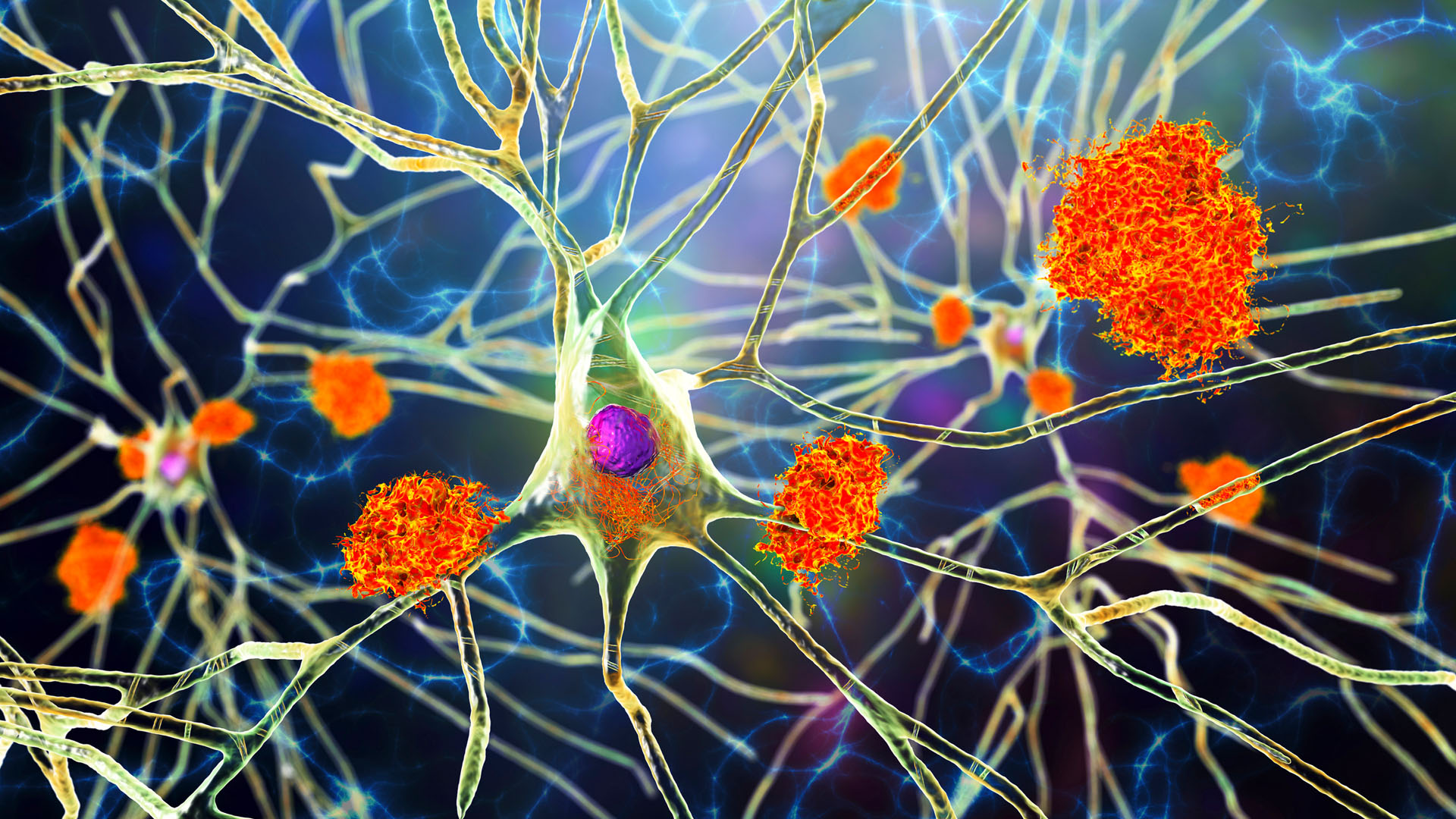

Alzheimer's disease is characterized by specific pathology — amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, Dr. Deborah Lee, a medical doctor and writer for Dr Fox Online Pharmacy in the U.K, told Live Science in an email. Amyloid plaques are abnormal protein clumps, while neurofibrillary tangles are bundles of nerve fibers.

Whether and how these tangles and plaques cause Alzheimer's is still unclear, but "it seems highly unlikely that just exercising the brain could prevent or reverse these major changes," Lee said. "Brain training will support residual brain function but is unlikely to provide a therapeutic treatment."

A study in the New England Journal of Medicine tested whether crossword puzzles or board games can slow disease progression in patients at risk of dementia who show signs of mild cognitive impairment. Among the 107 participants, cognitive scores were improved by crosswords and worsened by games in week 78 of the study. However, the long term implications of these results remain to be seen. In other studies, most specially developed "brain training" exercises have not been found to prevent or delay the progression of cognitive impairment, said Dr. Bal Athwal, a consultant neurologist at The Wellington Hospital in the U.K.

When it comes to treating Alzheimer’s, a 2017 systematic review in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease concluded that, despite some positive findings, sampled studies were not adequate in several areas to say whether or not brain training was an effective treatment for those with Alzheimer’s Disease.

According to Alzheimer's Research UK, researchers believe challenging the brain helps to build a person's "cognitive reserve" — the brain's ability to adjust to the damage done by diseases such as Alzheimer's and keep working properly.

A 2022 study in the journal Neurology did find that people with high levels of cognitive reserve by the time they reached the age of 69 were less likely to notice a deterioration in their memory and thinking skills. Having a higher reading ability, challenging work and engaging in social and leisure activities were all linked to slower rates of decline. However, the researchers noted that those who stayed in the study until the end were more likely to be the types of people who were socially and intellectually privileged, therefore having greater cognitive reserves as a result of their experiences and lifestyles, possibly creating biased results. Participants who had more health problems and lower cognitive function were more likely to drop out of the study.

But that isn't to say that brain training is redundant. Continually practicing cognitive skills — such as paying attention, problem solving and utilizing memory — strengthens neural connections in a similar way to building muscle strength by regular visits to the gym, Lee said. "Brain training can target weaker aspects of brain function and help bring it into line," she said. "It can also improve reaction time." So while research indicates that brain training may help contribute to cognitive reserve, indirectly helping build resilience to Alzheimer’s disease, the results of longer term studies will help us determine just how useful it is.

“Neuroplasticity” or the brain’s ability to form new connections and neural pathways, may help to prevent cognitive decline. It is also thought that brain training exercises can be particularly beneficial for people who are middle-aged or older, Athwal said, as the activities can help promote and strengthen connections within the brain, helping people to stay mentally active. This was evidenced in a 2011 study in the journal Neuroimage, where researchers concluded that demanding tasks led to improved neural efficiency in older adults.

When it comes to Alzheimer's, however, the research is simply not there to suggest that brain training can either prevent or treat the disease.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lou Mudge is a health writer based in Bath, United Kingdom for Future PLC. She holds an undergraduate degree in creative writing from Bath Spa University, and her work has appeared in Live Science, Tom's Guide, Fit & Well, Coach, T3, and Tech Radar, among others. She regularly writes about health and fitness-related topics such as air quality, gut health, diet and nutrition and the impacts these things have on our lives.

She has worked for the University of Bath on a chemistry research project and produced a short book in collaboration with the department of education at Bath Spa University.