Why the British were doomed from the get-go in the American Revolutionary War

Poor planning and a lack of cooperation meant British strategy was destined to fail during the American Revolution.

Despite the common belief that arrogance and overconfidence played major roles in the loss of the 13 colonies in North America, Britain was actually well aware of how difficult the task of quelling the rebellion would be. There was no hope of conquering America — the territory was too big and available resources too meager.

At the outbreak of hostilities, the British Army numbered just 45,000 men, spread over a substantial global empire. It would take time to raise new troops and even the hiring of Hessian soldiers (German soldiers recruited to serve in the British Army) would require lengthy negotiations.

Related: Who inherits the British throne?

Therefore, the key men planning the war put together a strategy that promised disproportionate results in relation to the effort involved. The plan, which became known as the "Hudson strategy," involved operations along the Hudson River, running up from New York to Canada. This had always been a strategically important river and by taking control of it, British leaders hoped to isolate rebellious New England from the more moderate middle and southern colonies.

By isolating New England from its supply base to the south, Britain believed the American rebellion could be strangled into submission.

The first missteps

Two British armies were tasked with taking control of the Hudson. The larger, under the command of William Howe, would move up the Hudson from New York, while a smaller army, under the command of Guy Carleton, would travel down the river from Canada. The plan became somewhat muddled at this point, as it was unclear whether the two armies were expected to actually meet, or if they were simply to set up various strongholds along the length of the river.

Stage one of the strategy was achieved without difficulty when Howe took control of New York in September 1776, but Carleton's progress was slow and he eventually abandoned his southward push.

Related: 3 skeletons found in Connecticut basement might be from Revolutionary War soldiers

This set the scene for a spectacular breakdown in cooperation between British forces, which doomed the Hudson strategy to failure. With a new commanding officer, John Burgoyne, the northern army again began its push down the Hudson in the next campaign. Burgoyne was confident and bold and he wasn't about to turn back, as Carleton had done.

Except this time, there was no army marching up the Hudson to support Burgoyne. Howe had decided to go south and capture Philadelphia instead, and the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord George Germain, had acquiesced in this unilateral abandoning of the agreed strategy.

When Burgoyne ran into difficulties, Howe was not close enough to offer assistance and the result was the loss of an entire army at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777.

A failed southern strategy

Britain took some time to rethink its plan. Eventually, British war leaders agreed that the war would shift to the south, aiming to re-establish control in the less militant southern colonies. This would have the same effect of denying the northern colonies their supply base, but would require a smaller army to enact.

This was important, because the entry of France into the war had changed the scale of the fight entirely. Britain was more concerned now with protecting its West Indies possessions from the French.

Starting in South Carolina, with the capture of Charleston on May 11, 1780, Britain aimed to subdue the southern colonies region by region, raising loyalist forces to keep the peace while the small British army moved on to the next target. This second British strategy unravelled when the loyalist forces proved unable to match the fiercer patriot militia. Whenever the British army left an area, resistance would flare up behind it.

Related: Was this famous Revolutionary War hero intersex?

The commanding officer in the south, Lord Cornwallis, was also aware that his army was too small to defend any substantial area of territory, so he moved aggressively, targeting any remnants of organized resistance from American patriots. This worked at the Battle of Camden, where an American army under Horatio Gates was destroyed, but the momentum could not be maintained without an inevitable and debilitating erosion of his army from sickness, fatigue and battle casualties.

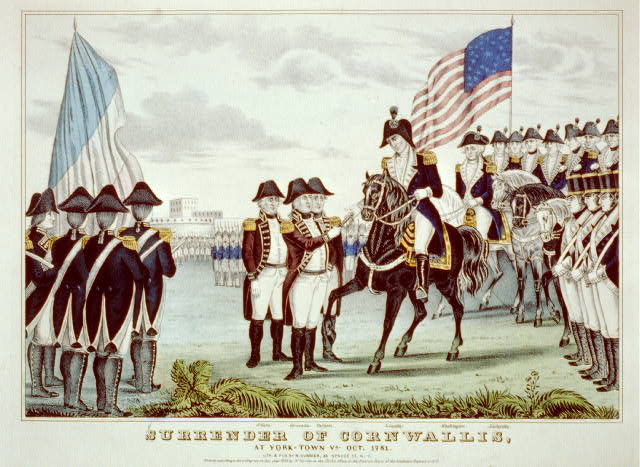

The British war effort eventually ran out of steam and ground to a halt at Yorktown. On October 19, 1781, Cornwallis surrendered his battered army to the Americans — the British strategies had failed.

This article was adapted from a previous version published in History of War magazine, a Future Ltd. publication.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

David is a freelance writer and visiting lecturer at the University of Chester in the U.K.. He has a PhD in history, an MA in military history from the University of Liverpool and a BA in American studies from the University of Iowa. He has published several books on American history including "The First Anglo-Sikh War 1845-46" (Osprey Publishing, 2019) and "William Howe and the American War of Independence" (Bloomsbury, 2015).