Bronze Age 'infinity pool' hosted supernatural water rituals, archaeologists say

A mysterious wooden structure built in Italy more than 3,000 years ago may have been a Bronze Age "infinity pool" that reflected the sky during religious rituals to give onlookers the impression they were looking into another realm, according to new research.

One of the authors of the new study has even likened the pool to England's famous Stonehenge monument, which also symbolically may have led people into another world.

The pool-like structure was likely built sometime between 1436 B.C. and 1428 B.C. — a time of great cultural change in the region, which reinforces the idea that was established for new ritual purposes, said Sturt Manning, an archaeologist at Cornell University in New York and one of the authors of a new paper describing the research.

Related: In photos: Take a walk through Stonehenge

"As you would have come up to this thing, as soon as you'd been able to start to see the surface, you would have seen effectively the edge of the land around the sky," Manning told Live Science. "And as you got close to it, then you would have just been looking at the [reflected] sky — so you'd have, in a sense, entered another world." Today's infinity pools are similar in their reflective beauty.

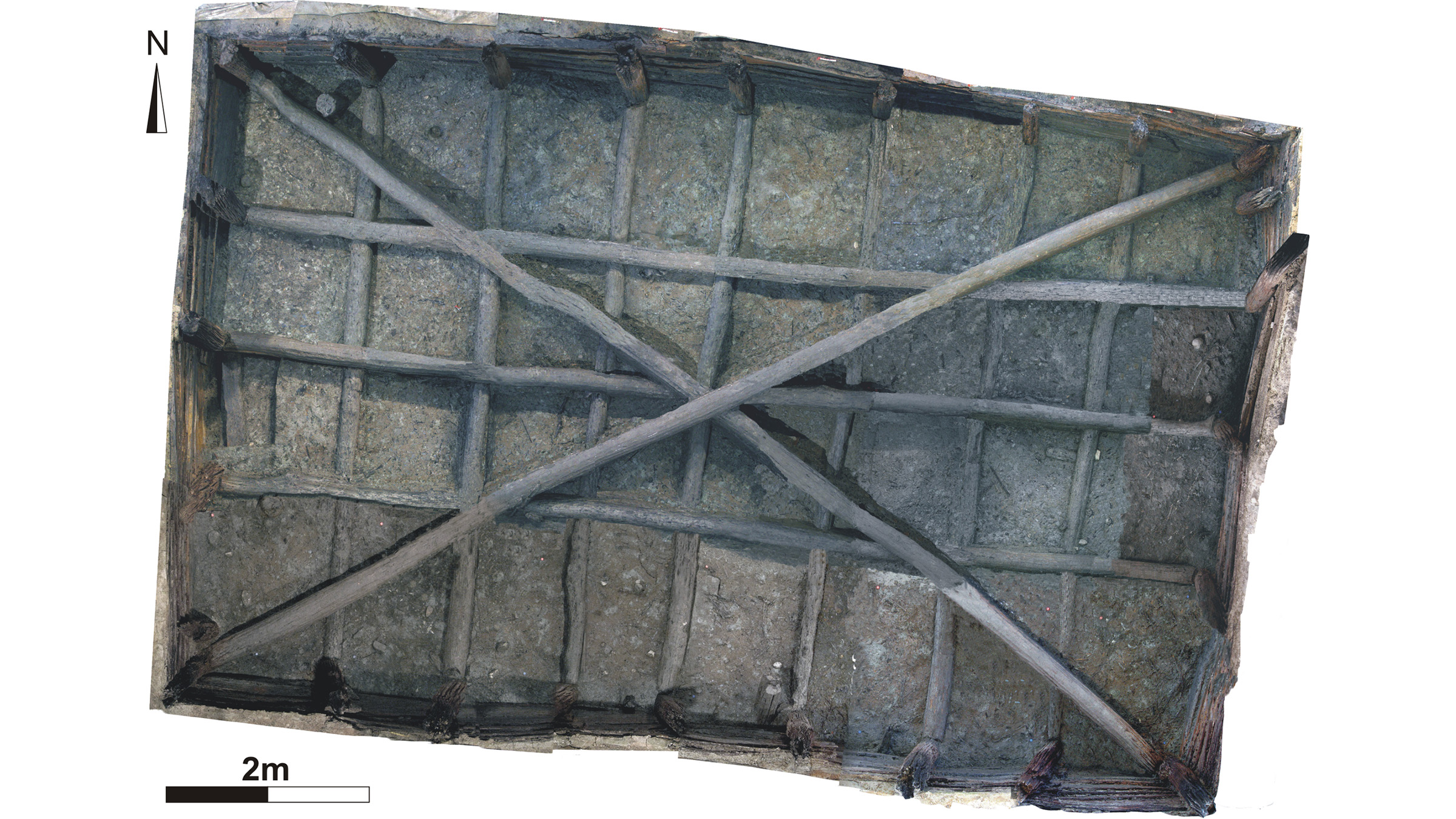

Italian archaeologists discovered the structure in 2004 near the town of Noceto, just west of Parma in Italy's northern Po Valley region. They called it "Vasca Votiva" — Italian for "votive" or "sacred" tank. The archaeologists noted that the pit was roughly 40 feet (12 meters) long, 23 feet (7 m) wide and more than 10 feet (3 m) deep. It had been excavated on a small hilltop and then lined with wooden poles, planks and beams; most of them were oak, but some were elm or walnut.

Layers of sediment showed that the structure had once contained water, although no channels to distribute water led away from it, and it seemed much too elaborate to have been just a reservoir for irrigation, Manning said. Previous research of ceremonial pots and wooden figurines found inside had revealed that the structure was built in the Bronze Age, probably between 1600 B.C. and 1300 B.C. But its exact age couldn't be verified, and its purpose had been a mystery. The new study resolves some of that uncertainty.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ancient timbers

Manning is a specialist in dendrochronology — the science of dating ancient wood — and he and his team joined the project with the hope that determining the age of the timbers used to line the Vasca Votiva could accurately reveal when it was built.

It's a difficult task; wood quickly rots when it is exposed to oxygen, and the record of dates for the growth of trees in ancient times often depends on rare finds of logs in the layers of sediment beneath ancient rivers and bogs, Manning said.

The team studied the growth rings from the timbers and measured each ring's levels of radioactive carbon-14, which is a naturally occurring fraction of the carbon that the trees absorbed while they were alive. The trees stopped absorbing carbon when they were cut down, and so the levels of carbon-14 that remain can be used to date when that happened.

Then, the team calculated when the timbers were harvested using "wiggle matching," in which they compared the patterns of carbon-14 absorption — the "wiggles" — with the distinctive patterns from trees that grew elsewhere in northern Europe at different times.

That enabled them to determine that the true date for the Vasca Votiva structure was in the middle of the 15th century B.C., which corresponded to a time of tremendous cultural change in northern Italy.

The dominant society in the region at that time, the Bronze Age Terramare culture, was transitioning from a simpler period of individual small farms to a period of greater social complexity, with the development of larger settlements that became cultural centers and an increased use of plowing and irrigation for farmland, the researchers wrote.

Reflecting waters

The new dates reinforce the idea that the mysterious structure at Noceto was built for new ritual and religious purposes established in the area, Manning said. There was no sign that the tank had ever been used as a simple reservoir for irrigation, and it was much too elaborately built; also, the ceremonial pots and figurines found inside it showed it was used for ritual offerings, he said.

As well, a great deal of labor would have been needed to complete the elaborate Vasca Votiva, and the excavations have shown that it was the second such structure at the same hilltop site. The first was even larger, and started about 10 years before the later structure; but discarded tools and wood shavings suggest that it collapsed as it was being built and so the latest tank was built over it, he said.

A few similar ceremonial water features have been found elsewhere in the ancient world, such as the earlier "lustral basins" found at Minoan sites on Crete that date back to at least the 15th century B.C., although those were smaller and typically made of clay and stone.

But nothing like this infinity pool has been found in northern Europe. "To our knowledge, it's unique in the area," Manning said.

He likened the Vasca Votiva to the Neolithic Stonehenge monument in southern England. Although Stonehenge is on a much larger scale, "you have these avenues leading to a particular ceremonial place; you're sort of leaving one world that you're part of and creating an impression that you've moved and joined another one," he said.

"It was like an infinity pool, in a sense, because it was up at the top of a hill; if you were standing near it, looking into it, you would see through the water and see some of the pots and other objects that have been deposited carefully in it," Manning added. "But you would also be very much looking at the sky and the clouds above you; it's hard not to think that this might have to do with rainfall and things like that."

The introduction of whatever supernatural water rituals took place at the Vasca Votiva in ancient times seems to have been an attempt to gain favor with the deities responsible for water and rainfall – elements that would have been vital to early farming communities, he said.

"If it was just for irrigation or something, then fine, but it doesn't seem to work for that," Manning said. "It's more about some group activity that they think is going to be beneficial, or that the gods are going to be pleased that they have done this."

The study was published June 9 in the journal PLOS One.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.