Viking warriors sailed the seas with their pets, bone analysis finds

A Viking cemetery in England doesn't just hold the cremated remains of these warriors but also the beloved animals they brought from Scandinavia.

When the Vikings sailed west to England more than a millennium ago, they brought their animal companions with them and even cremated their bodies alongside human ones in a blazing pyre before burying them together, a new study finds.

These animal and human remains were found in a unique cremation cemetery in central England that has long been assumed to hold the remains of Vikings — in particular, the warriors who sailed west to raid the countryside in the ninth century A.D. However, the new analysis revealed that several of the burial mounds didn't contain just the remains of humans but also those of domesticated animals that the warriors brought with them on their journey.

After the Vikings built a large funeral pyre, they added both human and animal remains to the conflagration.

"At Heath Wood, the people raked the remains of the pyre, removing portions of bone and mixing up what was left," study lead study author Tessi Löffelmann, a doctoral candidate in archaeology at Durham University in the U.K., told Live Science in an email. "I find this intriguing because that means there was no clear separation between animals and humans any longer — everything kind of became part of the same thing, something new."

Viking burial site

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a set of historical records written in Old English over several centuries, the so-called Viking Great Army invaded the southeastern coast of England in 865 and made its way inland. By 873, according to the Chronicle, the army reached the village of Repton, just a few miles from a cemetery now called Heath Wood. In the 1940s and 1950s, archaeologists found 59 separate burial mounds at Heath Wood and excavated 20 of them, finding Scandinavian grave goods — including swords and shields — and the remains of people with evidence of sharp force trauma.

In a paper published Wednesday (Feb. 1) in the journal PLOS One, an international team of researchers report their analysis of six humans and animals that were cremated together in an attempt to understand where they came from.

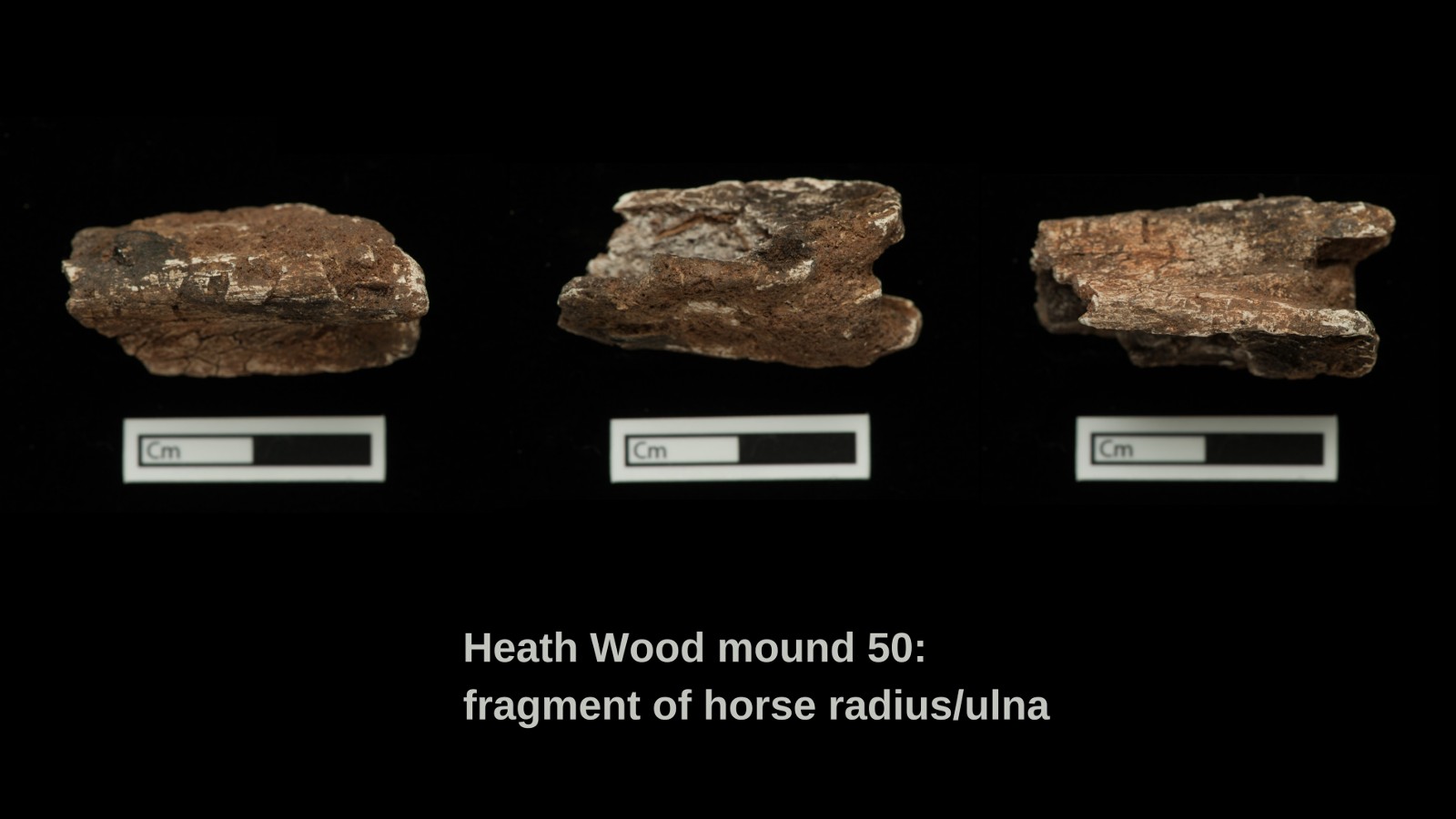

Most of the cremated remains that were studied came from one burial mound, which also included a sword hilt, silver and iron objects, and a fragment of a shield. Mixed in with the remains of an adult and a younger person were bones from a horse, a dog and what was likely a pig. An adult from another burial mound was also studied.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: 2 Viking swords buried upright might have connected the dead to Odin and Valhalla

Although chemical analysis of burned bone is a relatively new technique, the Heath Wood remains produced an interesting set of results. According to the team's study of the strontium isotopes — chemical variations that can indicate where a person or animal lived — the researchers found that all three animals and one of the adults were not born or raised in England. Rather, their strontium values were much closer to those found in the Baltic shield region of Scandinavia, a geological area that maps roughly to modern Norway and Sweden. This suggests that, shortly before their deaths, Viking warriors sailed west, bringing their animals with them.

"These results provide the first and unique evidence for the migration in the late ninth century of both people and their animals — including horses and dogs — across the North Sea, from Scandinavia to the heart of England," the researchers wrote in their study.

The fact that there are three different species of animals is intriguing, since they could have been used for multiple purposes, such as transportation or food. Löffelmann said she is not sure there was a functional reason for this selection. "I think that the horse and the dog certainly were companions but am less sure about the rest of the animals," she said. "We know that animals were intricately woven into the mythology of Scandinavia at the time." She also noted that identification of animal bone in cremation graves can be challenging, so there may have been more animals.

Viking archaeologist Cat Jarman, who was not involved in this research, told Live Science in an email that "Heath Wood is a hugely significant site in Viking Age England. The use of strontium isotope analysis on cremated remains is very exciting, and the possibility that horses and dogs were also moved large distances — even overseas — fits well with what we know from other parts of the Viking world."

Jarman is not convinced, however, that the Heath Wood burials represent members of the Viking Great Army. Archaeological work nearby shows that the area was settled by a Scandinavian group starting in the late ninth century, and Heath Wood includes radiocarbon dates up to the 10th century, much later than the army's raids. "This context only makes the study's results more exciting," Jarman said, "as it suggests an ongoing migration well beyond the historically recorded Great Army movements."

Regardless of the exact date, the Viking cremations at Heath Wood were almost certainly a unique sight to behold. Since Christianity had taken hold in England by this time, most people had long since switched to inhuming their dead. A cremation of this size would have required an enormous amount of energy, especially if there were animals in addition to humans on the pyre.

"It must have been a very large, open-air pyre that was managed for hours and hours," Löffelmann said. "I imagine that this whole event would have lasted well into the night, and the light would likely have been seen from nearby Repton," more than 3 miles (4.8 kilometers) away.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.