How Many Calories Can the Brain Burn by Thinking?

Here's how much energy you can burn when you put your mind to the test.

In 1984, the World Chess Championship was called off abruptly, due to the worryingly emaciated frame of Anatoly Karpov, an elite Russian player who was competing for the title. Over the preceding five months and dozens of matches, Karpov had lost 22 lbs. (10 kilograms), and competition organizers feared for his health.

Karpov's wasn't alone in experiencing the extreme physical effects of the game. While no chess competitor has experienced such profound weight loss since then, elite players can reportedly burn up to an estimated 6,000 calories in one day — all without moving from their seats, ESPN reported.

Is the brain responsible for this massive uptake of energy? And does that mean that thinking harder is a simple route to losing weight? To delve into that question, we first need to understand how much energy is used up by a regular, non-chess-obsessed brain.

Related: How Are Calorie Counts Calculated?

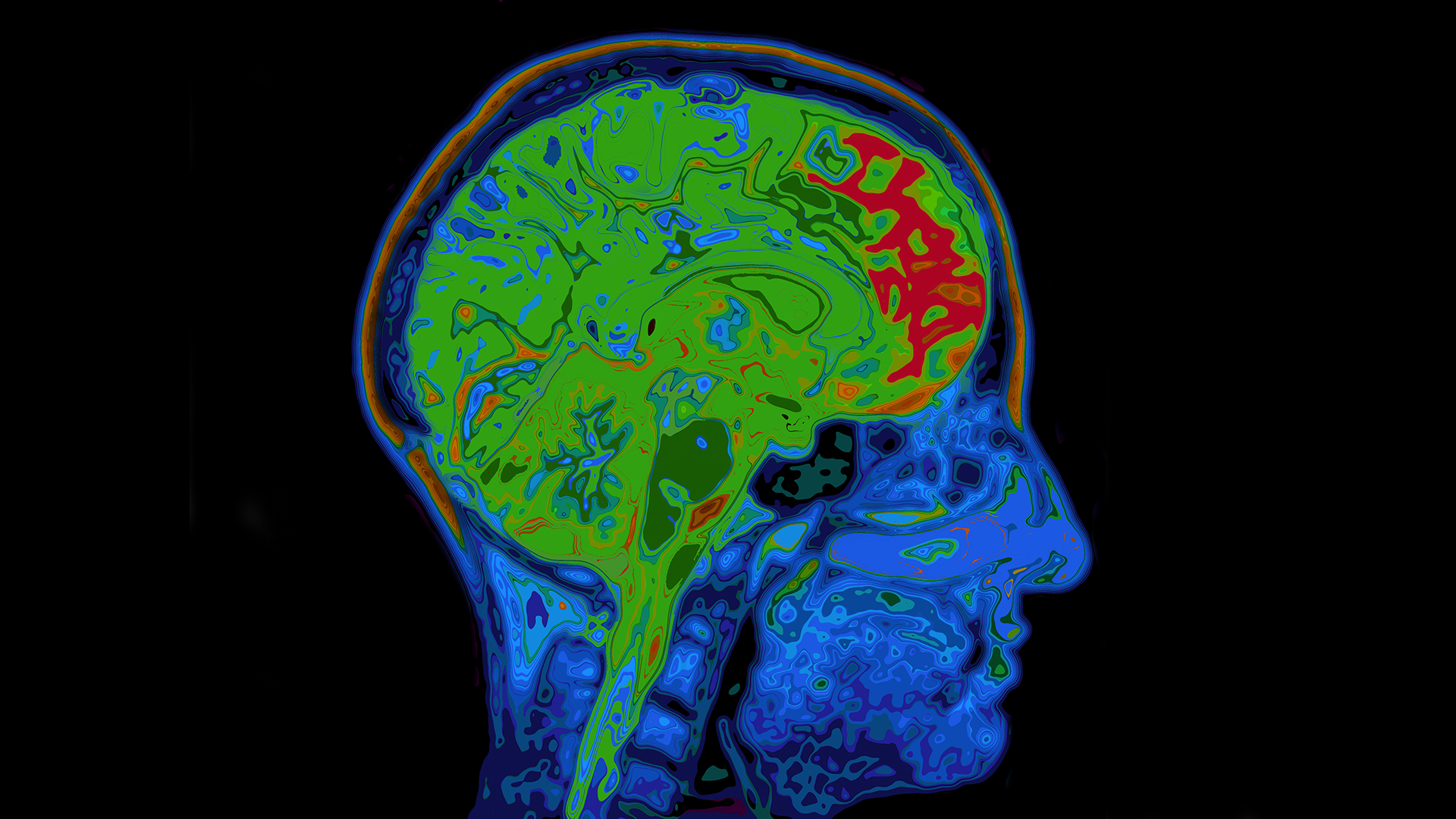

When the body is at rest — not engaged in any activity besides the basics of breathing, digesting and keeping itself warm — we know that the brain uses up a startling 20% to 25% of the body's overall energy, mainly in the form of glucose.

That translates to 350 or 450 calories per day for the average woman or man, respectively. During childhood, the brain is even more ravenous. "In the average 5- to 6-year-old, the brain can use upwards of 60% of the body's energy," said Doug Boyer, an associate professor of evolutionary anthropology from Duke University. Boyer researches anatomical and physiological changes associated with primate origins.

This glucose-guzzling habit actually makes the brain the most energy-expensive organ in the body, and yet it makes up only 2% of the body's weight, overall.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hungry brain

Humans aren't unique in this regard. Together with Duke University evolutionary anthropology graduate student Arianna Harrington, who studies energy usage in mammal brains, Boyer conducted research revealing that very small mammals such as the tiny tree shrew and the minuscule pygmy marmoset devote just as much of their body energy to the brain as humans do.

Boyer believes the reason is that despite brains being lightweight, human brains — and the similarly glucose-hungry brains in tree shrews and marmosets — are large relative to the rest of the body. "If you have a really big brain relative to your body size, then it's probably going to be more expensive metabolically," Boyer told Live Science.

Most of the energy hauled up by this organ is devoted to enabling neurons in the brain to communicate with each other, via chemical signals transmitted across cell structures called synapses, said Harrington. "A lot of the energy goes towards firing a synapse. That involves a lot of transportation of ions across membranes, which is thought to be one of the most expensive processes in the brain."

In addition, the brain never really rests, she explained; when we sleep, it still requires fuel to keep firing off signals between cells to maintain our body's functions. What's more, servicing the brain are fleets of cells that exist to channel nourishment toward neurons. And these cells also need their share of the body's glucose in order to survive and continue doing their job. The huge resources devoted to building a brain also help to explain why during periods of intensive development, when we're 5 or 6 years old, our brains scarf up almost three times the amount of energy that our adult brains need.

Exercising the mind?

Since the brain is such a big energy-guzzler, does that mean that the more we put this organ to work, the more energy it'll slurp up — and the more calories we'll burn?

Technically, the answer is yes, for cognitively difficult tasks. What counts as a "difficult"' mental task varies between individuals. But generally, it could be described as something that "the brain cannot solve easily using previously learned routines, or tasks that change the conditions continuously," according to Claude Messier, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of Ottawa in Canada, who has studied cognition, diabetes and brain metabolism. Such activities might include learning to play a musical instrument or plotting innovative moves during an intense game of chess.

"When you train to learn something new, your brain adapts to increase energy transfer in whatever [brain] regions are activated by the training," said Messier. Over time, as we become more skilled at performing a particular task, the brain no longer has to work as hard to accomplish it, and so doing that task will eventually require less energy, Messier explained.

Nevertheless, in those early stages of learning to perform a mentally taxing task, surely we can justify eating a sugary snack to boost our energy reserves?

Related: How Much Exercise Is Needed to Lose Weight?

If you simply feel the need for a mood-boosting sugar rush, then yes. But if you believe your deep thinking will burn off that sugary snack, then unfortunately, no.

Because against the backdrop of the brain's huge overall energy usage, which is devoted to a multitude of tasks, the energy required just to think harder is actually comparatively tiny. "Most of what's going on, what slurps up the brain's energy, is what we might call 'under the hood,''" explained Messier. "We are unaware of most of the activity going on in the brain. And a lot of that activity is unrelated to the conscious activities like learning how to sing or play the guitar," he said.

In other words, learning a new task or doing something difficult isn't actually the most energy-taxing part of the brain's work. In fact, "When we learn new things or learn how to do new activities, the amount of energy that goes into that 'new'' activity is rather small compared to the rest of the brain's overall energy consumption," Messier added.

As Harrington explained, "The brain is able to shunt blood [and thus energy] to particular regions that are being active at that point. But the overall energy availability in the brain is thought to be constant." So, while there might be significant spikes in energy use at localized regions of the brain when we perform difficult cognitive tasks, when it comes to the whole brain's energy budget overall, these activities don’t significantly alter it.

Pumped for action

But if that's true, how do we explain why Karpov grew too skinny to compete in his chess competition? The general consensus is that it mostly comes down to stress and reduced food consumption, not mental exhaustion.

Elite chess players are under intense pressure that causes stress, which can lead to an elevated heart rate, faster breathing and sweating. Combined, these effects burn calories over time. In addition, elite players must sometimes sit for as much as 8 hours at a time, which can disrupt their regular eating patterns. Energy-loss is also something that stage performers and musicians might experience, since they’re often under high-stress, and have disrupted eating schedules.

"Keeping your body pumped up for action for long periods of time is very energy demanding,” Messier explained. “If you can’t eat as often or as much as you can or would normally — then you might lose weight.”

So, the verdict is in: Sadly, thinking alone won't make us slim. But when you next find yourself starved of inspiration, one extra square of chocolate probably won't hurt.

- Are Big Brains Smarter?

- Do People Really Use Just 10% of Their Brains?

- Can You 'Speed Up' Your Metabolism?

Originally published on Live Science.

Emma Bryce is a London-based freelance journalist who writes primarily about the environment, conservation and climate change. She has written for The Guardian, Wired Magazine, TED Ed, Anthropocene, China Dialogue, and Yale e360 among others, and has masters degree in science, health, and environmental reporting from New York University. Emma has been awarded reporting grants from the European Journalism Centre, and in 2016 received an International Reporting Project fellowship to attend the COP22 climate conference in Morocco.