Helmet-headed Cambrian sea monster sucked up prey like a Roomba

Its size is "absolutely mind-boggling," said the scientist who described the fossil.

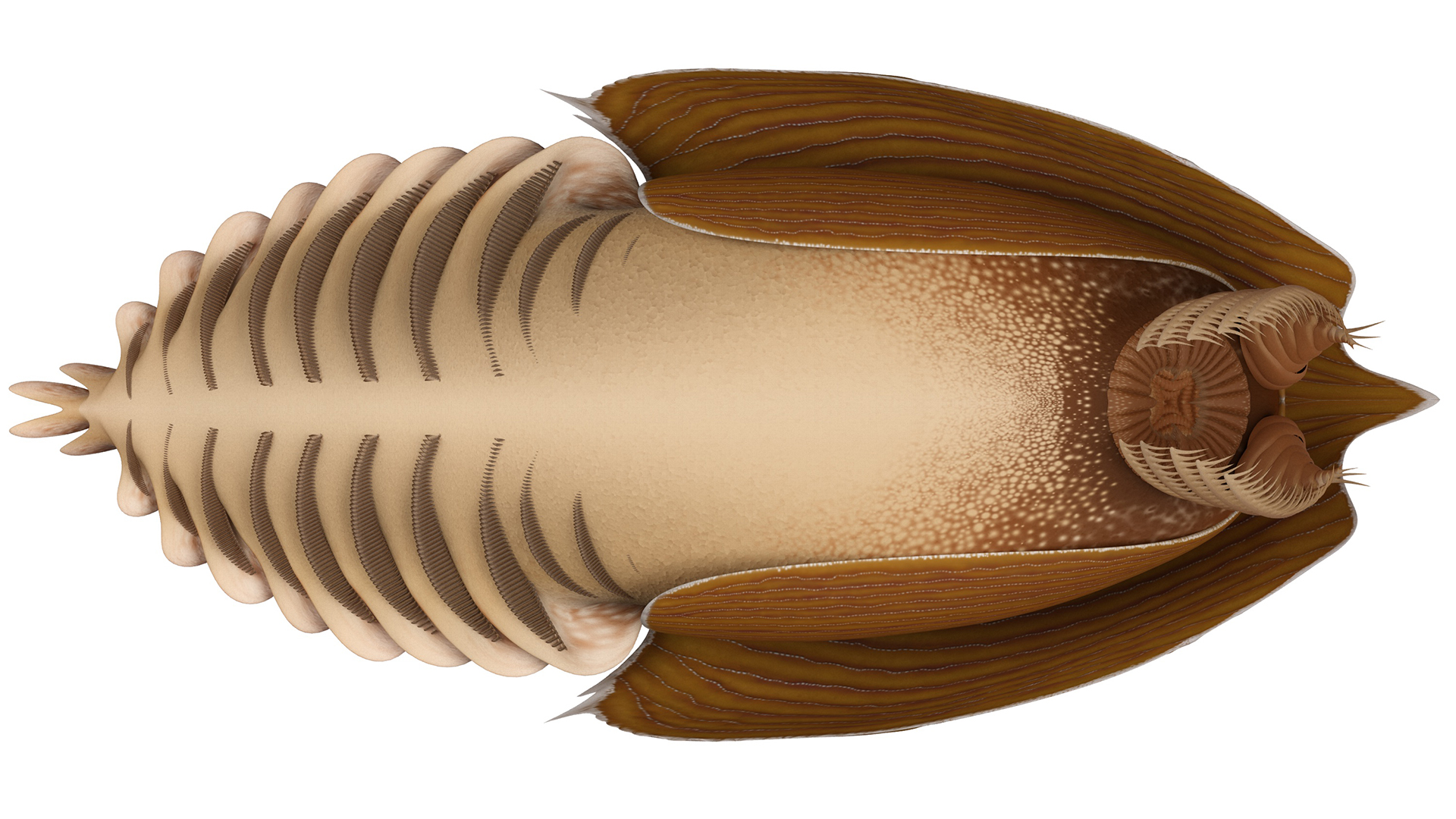

A creature with a massive head shield, sand-raking claws and a circular tooth-filled mouth swept across the ocean bottom half-a-billion years ago, hoovering up prey like a living Roomba.

Measuring nearly 2 feet (50 centimeters) long, Titanokorys gainesi — a newfound genus and species — had a flattened body and a broad head that made up approximately two-thirds of its total length, researchers reported in a new study.

Titanokorys was one of the biggest ocean predators of the Cambrian period (543 million to 490 million years ago) and is the largest-known Cambrian seafloor predator, according to a new study. Compared with most other sea life at the time, its size was "absolutely mind-boggling," lead study author Jean-Bernard Caron, a curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, said in a statement.

Related: Gallery of fantastic fossils

"It's like a swimming head in a big helmet," Caron told Live Science. "It's a very unusual shape."

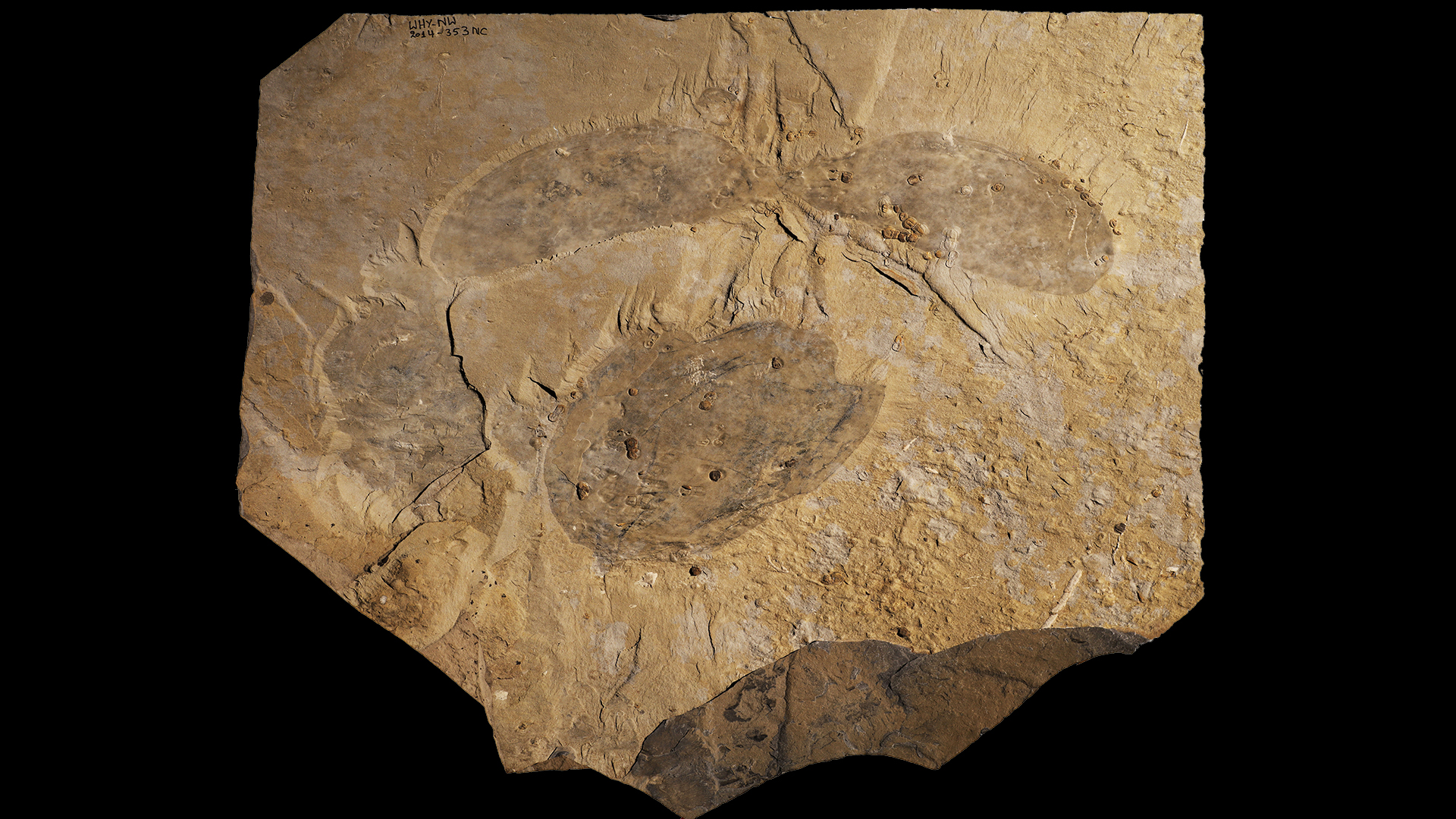

Caron and study co-author Joe Moysiuk, a doctoral candidate in the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto, pieced together the long-extinct creature's anatomy from 12 fossil fragments collected at the Burgess Shale, a fossil deposit in British Columbia, Canada, dating to about 508 million years ago.

Titanokorys' large head and protective carapace indicate that it was a hurdiid, a helmeted family in a group of extinct animals known as radiodonts, which had prominent eyes, clawlike appendages and circular, tooth-lined mouths. Radiodonts are early arthropods — invertebrates with exoskeletons, jointed limbs and segmented bodies. (Modern-day examples include insects and crustaceans.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists gleaned further anatomical details for Titanokorys by examining fossils of related Cambrian animals, such as Cambroraster falcatus, also from the Burgess Shale. This rake-clawed, helmet-headed creature's name references its resemblance to the Millennium Falcon from "Star Wars," and Moysiuk and Caron described it in 2019.

"It's a bit of a jigsaw puzzle story here, like many of its predecessors and many other radiodonts we've found in the past based on fragmentary evidence," Caron said. "It's very rare to find a complete specimen at Burgess Shale, especially large ones. Many of these animals lived along the seafloor and they were buried very quickly in mud. If you're small, you tend to be covered more easily than if you're large. If you're not covered, you're exposed to scavengers or decay, so that's why we don't find large, complete specimens — just bits and pieces."

Life existed on Earth long before the Cambrian, but during the early part of that period — about 541 million to 530 million years ago — animal bodies got weird. During this boom time for evolution, known as the Cambrian explosion, species evolved and diversified at an unparalleled pace, producing creatures with daggerlike tails; spiny arms; Swiss-army-knife heads; mouths full of needles; and bodies that were so densely covered with bristles they resembled kitchen brushes.

Most of the animals known from this period were small, about the length of a human finger. One notable exception, a gigantic, carnivorous shrimplike creature named Anomalocaris canadensis, measured up to 3 feet (1 m) long and was the Cambrian's biggest predator. But Anomalocaris lived and hunted in the ocean's water column, whereas Titanokorys offers the first evidence that big radiodont predators also evolved during the Cambrian to hunt on the sea bottom, Caron said.

"Anomalocaris was a knife-toothed predator, with claws that were adapted for grasping with specialized spines," he said. By comparison, broad and flat Titanokorys was built for bottom-feeding. The sturdy, spine-tipped carapace on its head would have plowed through marine sediments, while comblike structures on its claws would have swept prey toward its circular mouth, Caron explained. Identifying this large seafloor predator hints that big ocean predators may also have evolved to hunt in other niche environments during the Cambrian, he added.

The findings were published Sept. 8 in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.