'Cannibal CME' sun storm marks rise of new solar cycle in space weather

The sun is waking up — and making sure we all know it.

The sun is waking up — and making sure we all know it.

On Nov. 3 and 4, Earth was hit with a sizeable geomagnetic storm, the result of a series of outbursts from the sun on Nov. 1 and 2. Such outbursts are tied to sunspots, which are magnetic storms on the sun's surface. Both sunspots and solar activity ebb and flow on a cycle stretching about 11 years, and this week's storms are symptomatic of the sun's current stage in that cycle.

"The last several years really we've had very little activity, as is the case during solar minimum, but now we're ramping up and ramping up quite fast into the next solar cycle maximum, which we expect in 2025," Bill Murtagh, a program coordinator at the Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), told Space.com.

Related: Watch the sun fire off huge solar flares in this mesmerizing NASA video

"We're seeing the increase in activity that one would expect with this rise in the solar cycle," Murtagh said. "This is kind of our awakening phase."

And as this week's storms demonstrated, solar activity affects much more than just the sun — when it reaches Earth's neighborhood, solar outbursts can cause a set of phenomena called space weather with impacts ranging from beautiful auroral displays to satellite damage.

A storm from a 'cannibal' CME

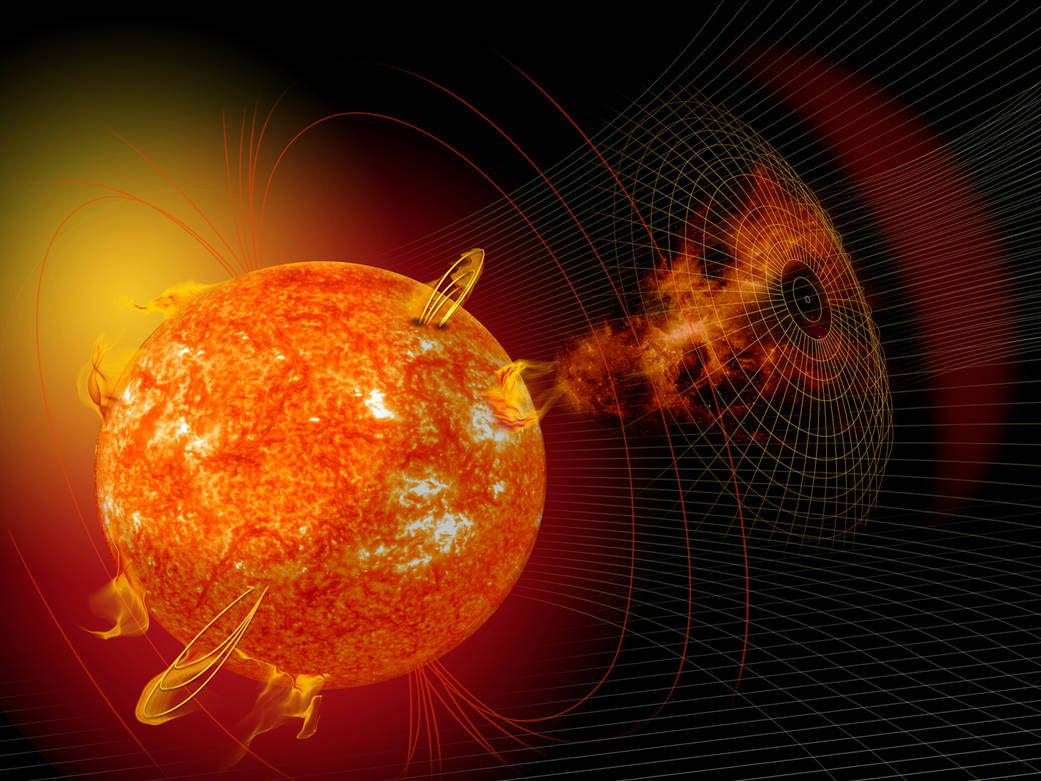

This week's geomagnetic storm originated in a series of coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, which are bubbles of solar material that the sun sometimes burps out. "A CME is essentially a billion-ton cloud of plasma gas with magnetic fields," Murtagh said, "so the sun shot a magnet out into space and that magnet made the 93-million-mile transit from the sun to the Earth." (That's 150 million kilometers.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Earth has its own magnetic field, and magnetic fields mixing in space don't always play nice together. "The two magnets are going to come together and that's going to create this geomagnetic storm," Murtagh said of a CME reaching Earth.

Sometimes, a CME can grow on its way across space. This week's geomagnetic storm originated from a series of outbursts that merged when a later CME moved faster than its predecessor. "That first CME essentially works its way through the 93 million miles and almost clearing a path out for other CMEs to come in behind it," Murtagh said. "Sometimes we use the term 'cannibalizing' the one ahead."

How strong such a storm is depends on both the size of the CME and how the two magnetic fields align. A big enough CME and the geomagnetic storm will be bad no matter what happens. But for medium-sized CMEs like the one that hit this week, the picture is more complicated.

Insert "This is kind of our awakening phase." here

Bill Murtagh, program coordinator, SWPC

That's because Murtagh and his colleagues can model how a CME will travel out from the sun across space, but they only learn a CME's magnetic field when the outburst reaches a NOAA spacecraft called Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), which hovers a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) toward the sun from Earth.

"The big, big events are the easy ones," Murtagh said. "Events like we had in the last couple of days are good examples of not-easy ones because they're not extreme, big powerful CMEs. They're pretty strong, but we don't know the magnetic structure in that CME until it hits the DSCOVR spacecraft."

And at that point, the CME will hit Earth within 20 or 30 minutes, so the geomagnetic storm is imminent.

Space weather on Earth

Geomagnetic storms aren't just an intriguing phenomenon. These events can interfere with crucial infrastructure, including power grids, navigation satellites and airplane radio communications in remote areas. That's why the Space Weather Prediction Center exists, of course: Murtagh and his colleagues monitor space weather to alert the operators of this infrastructure that trouble may be coming.

For a storm like this week's, the center automatically notifies all the power grid operators in the U.S. and Canada, Murtagh noted, although the risk of anything going truly awry is low. "They want the heads-up that it's happening so they know to be prepared," Murtagh said.

He said that the office heard reports of impacts in line with expectations for a storm of this scale.

"This kind of level of storming we've had hundreds of examples, so we have a good sense for what it will do to the grid," Murtagh said. "They're seeing it, they're feeling it, we're seeing some of those voltage irregularities ... but at this level of storming it's very manageable."

That may not always be the case. If the same "cannibal CME" phenomenon happens with larger outbursts, the impacts can be more serious.

"We have determined for all practical purposes that our worst-case scenario for the extreme geomagnetic storm event scenario will indeed be this." Murtagh said. "It's just that the CMEs were not that big — but that process happened here, where we had back-to-back two, three different CMEs came sweeping in together."

In 1989, for example, a solar storm caused a 12-hour blackout across the Canadian province of Quebec as the U.S. dealt with a host of energy losses, according to NASA. One of the largest known solar storms, 1859's Carrington Event took out telegraph systems and brought aurora to Hawaii, according to NASA.

"When we look back at the extreme geomagnetic storms all the way back to the famous 1859 Carrington Event, what we have concluded for practical purposes is that they're all associated with multiple CMEs," Murtagh said.

Unfortunately, space weather is even harder to predict than weather at Earth's surface.

Much of that is because scientists are still working to understand how the sun actually works. NASA's Parker Solar Probe and the European-American Solar Orbiter missions are producing data that will help scientists tackle those unknowns, but they don't make forecasting any easier right now, Murtagh noted.

"We've got some skill in forecasting the solar cycle, but we're not great at it just yet, so it could easily come in stronger," Murtagh said. "There are a lot of unknowns in the space weather business."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.