Who was Carl Linnaeus?

Linnaeus' ordered universe has influenced many generations of prominent scientists, including Charles Darwin and Gregor Mendel.

Carl Linnaeus was the famous 18th century Swedish botanist and naturalist who created the basic biological taxonomy — the so-called binomial classification system — that is the foundation of our modern taxonomic system. Linnaeus' classification, at its most basic, uses the dual "genus, species," nomenclature to classify organisms — everything from slime molds and bacteria to elephants and humans. All biologists, from first-year biology undergraduates to Ph.D. ecologists, use this basic system.

Today, Linnaeus occupies an honored place among the world's biologists, but for non-scientists he is largely a forgotten figure, often just a name faintly remembered from a half-forgotten biology class. But during his lifetime, and especially at his death, Linnaeus was a celebrity. He was praised throughout Europe as one of the continent's greatest minds. According to Uppsala University in Sweden, the famous German poet Goethe wrote of Linnaeus, "With the exception of Shakespeare and Spinoza, I know no one among the no longer living who has influenced me more strongly."

A blossoming interest in nature

Linnaeus was born in 1707 in the southern Swedish province of Småland, approximately 150 miles (241 kilometers) west of Stockholm. His father was a Lutheran minister and amateur botanist who helped instill a love of nature in his son. Linnaeus was especially fond of plants and flowers and was given his own plot of land to start a small garden. According to William MacGillivray's book "Lives of Eminent Zoologists" (Oliver and Boyd, 1834), Linnaeus "devoted a great part of his earlier years to the cultivation of a corner of the family-garden, which he profusely stocked with wild plants collected in the woods and fields."

Linnaeus's parents made sure their young son received an extensive education. His father, Nils, taught him Latin, geography and religion in the hope he would become a clergyman. Later, his parents employed a personal tutor to continue the boy's education in these subjects. Eventually, Linnaeus continued his schooling at the Vaxjo Gymnasium, a school that was designed to prepare young men for careers in the clergy. But his first love was botany. While ostensibly studying for the clergy, he continued to study botany, reading everything he could find on the subject.

"He nearly flunked out of [the school]," said Karen Beil, the author of "What Linnaeus Saw" (W.W. Norton and Company, 2019), "because he was usually off rummaging around in some meadow or marsh collecting plants rather than studying Latin and Greek."

It was at Vaxjo that Linnaeus met Johann Rothman, Beil wrote. Rothman was a physician and botanist who was influential in introducing Linnaeus to the period's botanical literature and taught the young man to classify plants using the taxonomic system of the day. By this time, Linnaeus's father realized that his son would never join the clergy, so reluctantly allowed him to pursue medicine, a career path suggested to Nils by Rothman and one that required students to be well-versed in botany.

At age 21, Linnaeus entered Lund University in Sweden, but the next year he transferred to Uppsala University, the country's oldest and most prestigious center of higher learning. He studied botany and medicine at the university, according to Beil. His expertise impressed his professors so much that he began to teach classes as an undergraduate, frequently lecturing on botany. During a break in his studies, he traveled to the far north of Scandinavia, to the region known as Lapland on a six-month long research expedition sponsored by the Uppsala Academy of Sciences. The goal was to collect and record different species of plants, animals and minerals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"He went on horseback, traveling up to the Arctic Circle and around the Gulf of Bothnia and into Finland," Beil said. "He collected some 400 species of plants, many of which were previously unknown to the scientists of the time."

Related: Cost to identify all unknown animals: $263 billion

He also studied the indigenous Sami people (also known as Laplanders) who inhabited the region and were nomadic reindeer herders, hunters and fishermen. He kept a journal, Beil said, in which he "recorded everything from the way [the Sami] made their beds from moss to how they made their bread."

All Swedish medical students were required to receive their degrees outside Sweden, so Linnaeus finished his studies at the University of Harderwijk in the Netherlands in 1735. His doctorate was focused on the causes of malaria, Beil said, a malady he erroneously attributed not to mosquitoes but to regions with clay-rich soils. He remained in the Netherlands for another three years, enrolling in the University of Leiden to continue his studies.

His time in the Netherlands played a major role in his education. "While there, he ended up befriending all of the greatest scientists of the day, many of them becoming mentors to him," Beil said.

He soon returned to Sweden, married, and set up his medical practice. He also helped found the Royal Swedish Academy of Science. He did not remain a practicing doctor for long, but was appointed professor of medicine at Uppsala University in 1741, eventually becoming rector of the school (similar to a Dean) in 1750. During his tenure, he was responsible for maintaining the university's Botanical Garden, a task he carried out with enthusiasm, arranging the plants according to his own Linnaean classification.

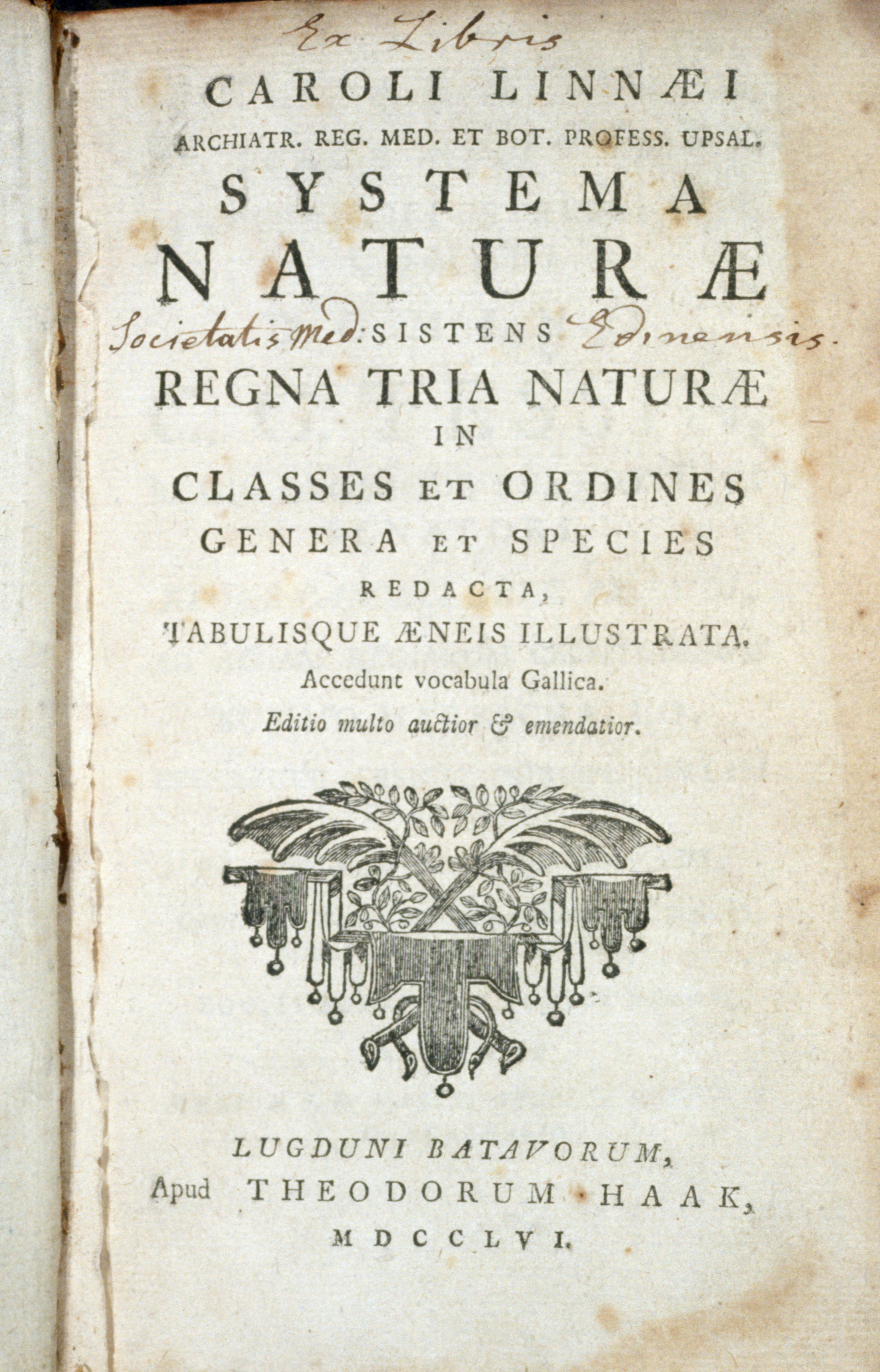

His pivotal work: Systema Naturae

In the same year Linnaeus finished his doctorate, he published a brief pamphlet that would eventually revolutionize the fields of biology and scientific taxonomy.

"Originally it was just his list that organized all plants, animals and minerals," Beil said. "But it became a blueprint for the world's scientists to follow to classify nature. He kept revising and expanding it for the rest of his life."

This "list" was written in Latin and was called Systema Naturae ("The System of Nature"). It proposed a radical new approach to the ordering and classification of plants and animals. His system was hierarchically ranked, meaning that organisms were grouped into successively larger groups based on morphological traits (that is, physical attributes). At the broadest level, the classification system was divided into three broad kingdoms: animals, plants and minerals (the mineral designation was subsequently dropped). These categories were further subdivided into increasingly specific designations, which included "classes," "orders," "genera," and "species."

Related: Ancient mystery creature that defied classification is Earth's oldest animal

Scientific classification during the 18th century was chaotic, Beil said. There were several different classification schemes in vogue and new specimens were being discovered all the time, especially from areas outside Europe that were the focus of European colonization. These specimens were scrutinized by scientists from different countries, each of whom used his own method and terminology. This led to many of the same species acquiring several different names, frequently in different languages. And often the names would be interminably long, complex and unwieldy — essentially a long list of the organisms' attributes so that a single organism might be identified using upwards of ten or more words. In her book, Beil gives the example of asparagus, which, prior to the Linnaean system, was classified as Asparagus caule inermi fruticoso, folis aciformibus perennantibus mucronatis termis aequalibus. In short, the classification schemes in existence before Linnaeus' system were confusing and idiosyncratic and there was little effort, if any, to systematize the methods.

Systema Naturae grew out of practical reasons, Beil said. "Linnaeus was just trying to standardize everything," she said. "He was attempting to bring a little order. He had a hyper-organized mind and he was an obsessive list-maker, so I think that helped him 'clear the desktop of science' by bringing order to taxonomy."

At its most basic level, the Linnaean system assigns each unique species of organism two names, hence the identification of the system as a binomial (two-named) classification. Although similar two-named systems had been used in the past, Beil said, they had never been used in any systematic manner, nor had they been used consistently.

Linnaeus combined two terms, genus and species, and used this combination to identify each particular organism. The species designation, a term he borrowed from the English naturalist and parson John Ray, indicates the most basic unit of classification, traditionally defined as organisms capable of interbreeding. The genus designation (gens is Latin for "tribe") ranks above species and designates the larger group of related organisms. For example, a coyote (Canis latrans) is a different species from a wolf (Canis lupus), but both belong to the same genus, Canis. This genus, in turn, could then be related to the higher-order ranks, such as order (Carnivora), class (Mammalia) and so on, all the way up to the highest rank, the kingdom ranking (Animalia).

Related: The 10 weirdest medical cases in the animal kingdom

Linnaeus continued to revise Systema Naturae throughout his lifetime. It eventually grew from 11 pages in the first edition to more than 2,000 pages, Beil said, as new species were added over time. Linnaeus also made several changes, such as changing the classification of whales from fishes to mammals in the 10th edition, which was published in 1758. In all, Linnaeus classified some 7,700 plants and 4,400 animals during his lifetime, Beil said.

Today, Systema Naturae is recognized as one of Western Civilization's most important scientific works. Although Linnaeus was ignorant of Darwinian evolution and modern genetic concepts, and, in fact, the modern binomial system differs from Linnaeus' system in many important respects, the principles laid down in Systema Naturae are the basis for modern taxonomy.

Linnaeus' legacy

Linnaeus spent many years teaching at Uppsala University where he was a popular lecturer and enjoyed considerable status as an important man of science and an authority on botany. He corresponded with many prominent scientists and continued to work and write, producing several more influential works, including "Philosophia Botanica" and "Species Plantarum," the latter considered by many to be the most important early treatise on botanical nomenclature. He was especially famous for his field trips, Beil said, which were basically botanical excursions during which he took students out into the countryside to collect plants.

Several of his most promising students, facetiously called the "apostles," went on to successful botanical and natural history careers, many of whom carried out famous zoological or botanical expeditions. One of these, Daniel Solander, became the chief naturalist on Captain James Cook's first Pacific voyage, Biel said.

Eventually Linnaeus bought a large estate in Hammarby, just outside Uppsala. There he built a museum to house his extensive natural history collections, which had grown throughout his life as scientists from all over the world sent him specimens. The estate also contained a garden in which he cultivated both native and exotic plants.

For his numerous accomplishments he was made a nobleman by the King of Sweden in 1761. After many years of teaching at Uppsala University, Linnaeus retired in 1772 and lived on his estate until his death in 1778.

Linnaeus' work influenced many scientists who came after him, including Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace and Gregor Mendel. His natural history collections and manuscripts are currently held by the Linnean Society in London, an international society for the study of natural history.

Additional resources:

- Watch a short film about Carl Linnaeus, from London's Natural History Museum.

- Learn more about Linnaeus' life and studies at The Linnaeus Museum in Sweden.

- Find more videos and information about Linnaeus at The Linnean Society of London's website.

Tom Garlinghouse is a journalist specializing in general science stories. He has a Ph.D. in archaeology from the University of California, Davis, and was a practicing archaeologist prior to receiving his MA in science journalism from the University of California, Santa Cruz. His work has appeared in an eclectic array of print and online publications, including the Monterey Herald, the San Jose Mercury News, History Today, Sapiens.org, Science.com, Current World Archaeology and many others. He is also a novelist whose first novel Mind Fields, was recently published by Open-Books.com.