People who live to 100 have unique gut bacteria signatures

These bacteria could contribute to a healthy gut and, in turn, healthy aging.

People who live to age 100 and beyond may have special gut bacteria that help ward off infections, according to a new study from Japan.

The results suggest that these bacteria, and the specific compounds they produce — known as "secondary bile acids" — could contribute to a healthy gut and, in turn, healthy aging.

Still, much more research is needed to know whether these bacteria promote exceptionally long life spans. The current findings, published Thursday (July 29) in the journal Nature, only show an association between these gut bacteria and living past 100; they don't prove that these bacteria caused people to live longer, said study senior author Dr. Kenya Honda, a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the Keio University School of Medicine in Tokyo.

"Although it might suggest that these bile-acid-producing bacteria may contribute to longer life spans, we do not have any data showing the cause-and-effect relationship between them," Honda told Live Science.

Related: How long can humans live?

Gut microbe "signature"

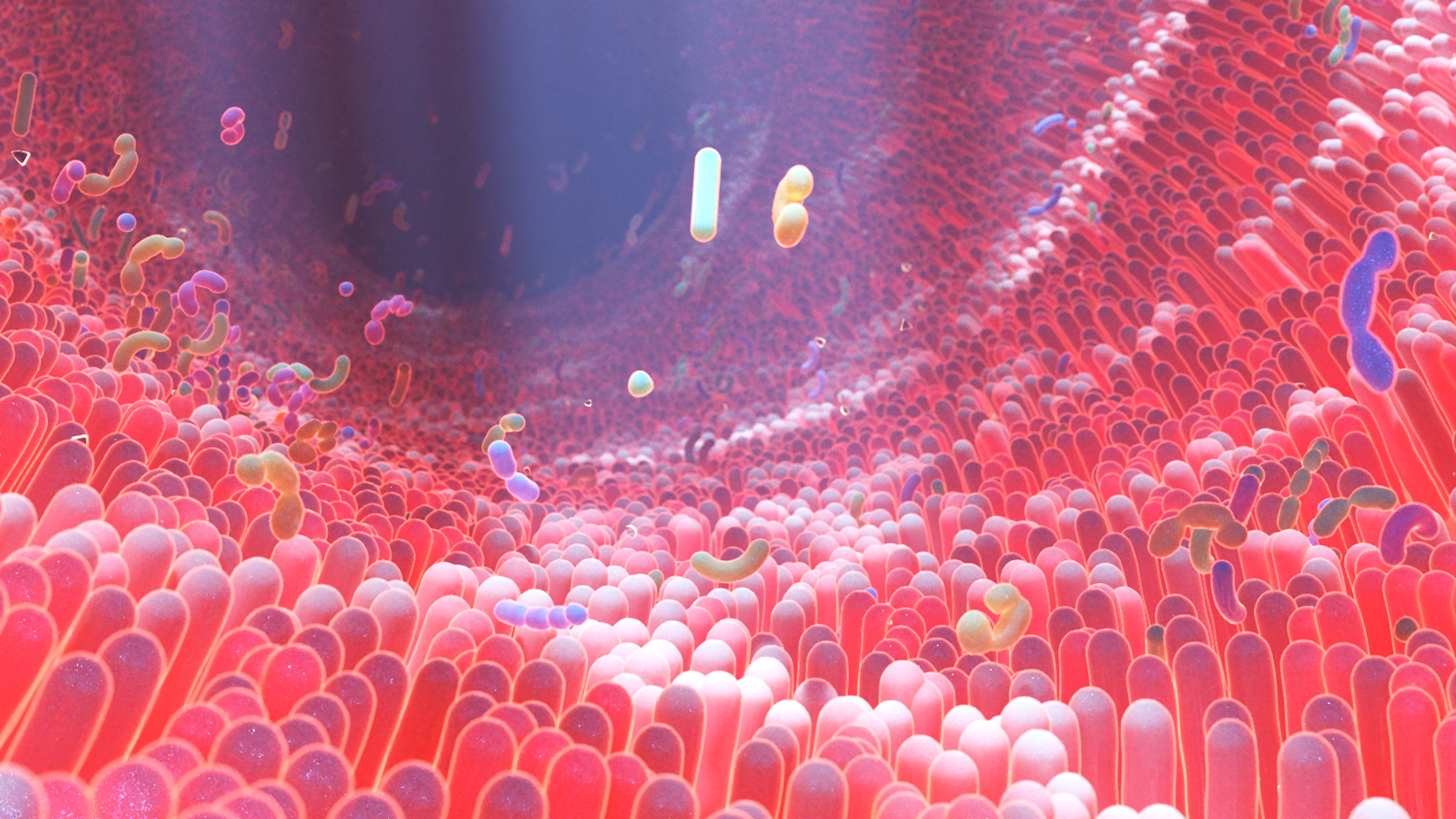

The community of bacteria and other microorganisms that live in the gut, known as the gut microbiome, is known to play a role in our health and changes as we age. For example, having less diversity in the types of gut bacteria has been linked with frailty in older adults. But researchers suspected that people who reach age 100 may have special gut bacteria that contribute to good health. Indeed, centenarians tend to be at lower risk of chronic diseases and infections compared with older adults who don't reach this milestone.

In the new study, the researchers examined the gut microbiota of 160 centenarians, who were, on average, 107 years old. They compared the centenarians' gut microbiota to those of 112 people ages 85 to 89, and 47 people ages 21 to 55.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that centenarians had a distinct "signature" of gut microbes not seen in the other two age groups. For example, certain species of bacteria were enriched or depleted in centenarians compared with the other two groups.

The researchers then analyzed gut metabolites (products of metabolism) in all three groups, and found that centenarians had significantly higher levels of so-called secondary bile acids compared with the other two groups.

Bile is the yellow-green fluid that's made by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, according to the National Institutes of Health. Bile acids are compounds in bile that aid in digestion, particularly of fats. After the liver produces bile acids, they are released into the intestine, where bacteria chemically modify them into secondary bile acids, according to a 2009 paper published in the journal Diabetes Care.

The researchers found particularly high levels of a secondary bile acid called isoallolithocholic acid (isoalloLCA) in the centenarians. The authors didn't know what metabolic process bacteria used to produce isoalloLCA, so they set out to identify the pathway. They screened gut bacterial strains from a 110-year-old who had particularly high levels of secondary bile acids and found that bacteria belonging to a family called Odoribacteraceae produced isoalloLCA.

What's more, isoalloLCA was found to have potent antimicrobial properties, meaning it could inhibit the growth of "bad" bacteria in the gut. In experiments in lab dishes and in mice, the authors found that isoalloLCA slowed the growth of Clostridium difficile, a bacterium that causes severe diarrhea and inflammation of the colon. IsoalloLCA also inhibited the growth of vancomycin-resistant enterococci, a type of antibiotic-resistant bacteria known to cause infections in hospital settings.

The findings suggest that isoalloLCA may contribute to a healthy gut by preventing the growth of bad bacteria.

They also suggest that these bacteria or their bile acids could treat or prevent C. difficile infection in people, Honda said, although more research would be needed to show this.

If these bile-acid-producing bacteria do contribute to a healthy gut, they might one day be used as a probiotic to improve human health, Honda said. He noted that these bacteria appear safe, as they don't produce toxins or harbor antibiotic-resistance genes.

It's unclear how centenarians come to acquire these beneficial bacteria, but both genetics and diet could play a role in shaping the composition of people's gut microbiota, Honda said.

The study did not collect information on participants' diet, exercise habits or medication use, all of which could affect gut microbiota and help to explain the link, the authors said.

Future studies that follow large groups of people over time could further probe the link between these bacteria and longevity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.