New wonder material designed by AI is as light as foam but as strong as steel

The new technique could produce materials for use in helicopters, airplanes and spacecraft.

Scientists have used artificial intelligence (AI) to design never-before-seen nanomaterials with the strength of carbon steel and the lightness of styrofoam.

The new nanomaterials, made using machine learning and a 3D printer, more than doubled the strength of existing designs. The scientists behind the new study said they could be used in stronger, lighter and more fuel-efficient components for airplanes and cars. They published their findings Jan. 23 in the journal Advanced Materials.

"We hope that these new material designs will eventually lead to ultra-light weight components in aerospace applications, such as planes, helicopters and spacecraft that can reduce fuel demands during flight while maintaining safety and performance," co-author Tobin Filleter, a professor of engineering at the University of Toronto, said in a statement. "This can ultimately help reduce the high carbon footprint of flying."

In many materials, strength and toughness can often be at odds. Take a ceramic dinner plate, for example: while plates are usually strong and can carry heavy loads, their strength comes at the cost of toughness — it doesn’t take much energy to make them shatter.

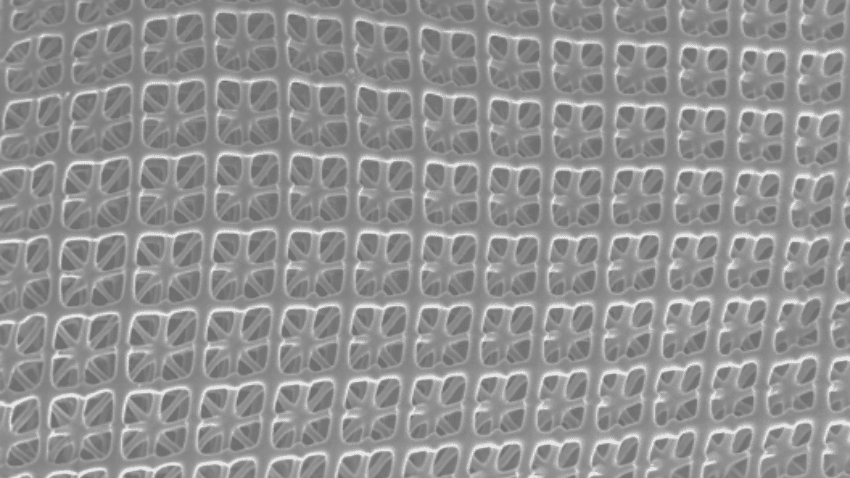

The same problem applies to nano-architectured materials, whose construction from multitudes of tiny, repeating building blocks 1/100th the thickness of a human hair makes them strong and stiff for their weight, but can also cause stress concentrations that lead to sudden breakages. So far, this tendency to shatter has limited the materials' applications.

"As I thought about this challenge, I realized that it is a perfect problem for machine learning to tackle," first-author Peter Serles, an engineering researcher at Caltech, said in the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To search for better ways to design nanomaterials, the researchers simulated possible geometries for their design before passing them through a machine learning algorithm. By learning from the designs they had generated, the algorithm was able to predict the best shapes that would evenly distribute applied stresses while also carrying a heavy load.

With these shapes in hand, the researchers used a 3D printer to create their new nanolattices, finding that they could withstand a stress of 2.03 megapascals for every cubic meter per kilogram — a strength five times higher than titanium.

"This is the first time machine learning has been applied to optimize nano-architected materials, and we were shocked by the improvements," Serles said. "It didn’t just replicate successful geometries from the training data; it learned from what changes to the shapes worked and what didn’t, enabling it to predict entirely new lattice geometries."

The researchers said their next steps will center on scaling up the materials until they can be used to make bigger components, while also searching for even better designs using their process. The primary aim is to design much lighter and stronger components for vehicles in the future.

"For example, if you were to replace components made of titanium on a plane with this material, you would be looking at fuel savings of 80 litres per year for every kilogram of material you replace," Serles said.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.