Watch atoms fuse into world's 'smallest bubble' of water in 1st-of-its-kind 'nanoscale' video

A new study captured never-before-seen footage of hydrogen and oxygen atoms combining to form a miniature water droplet out of "thin air." The newly improved reaction could one day help astronauts make water in space.

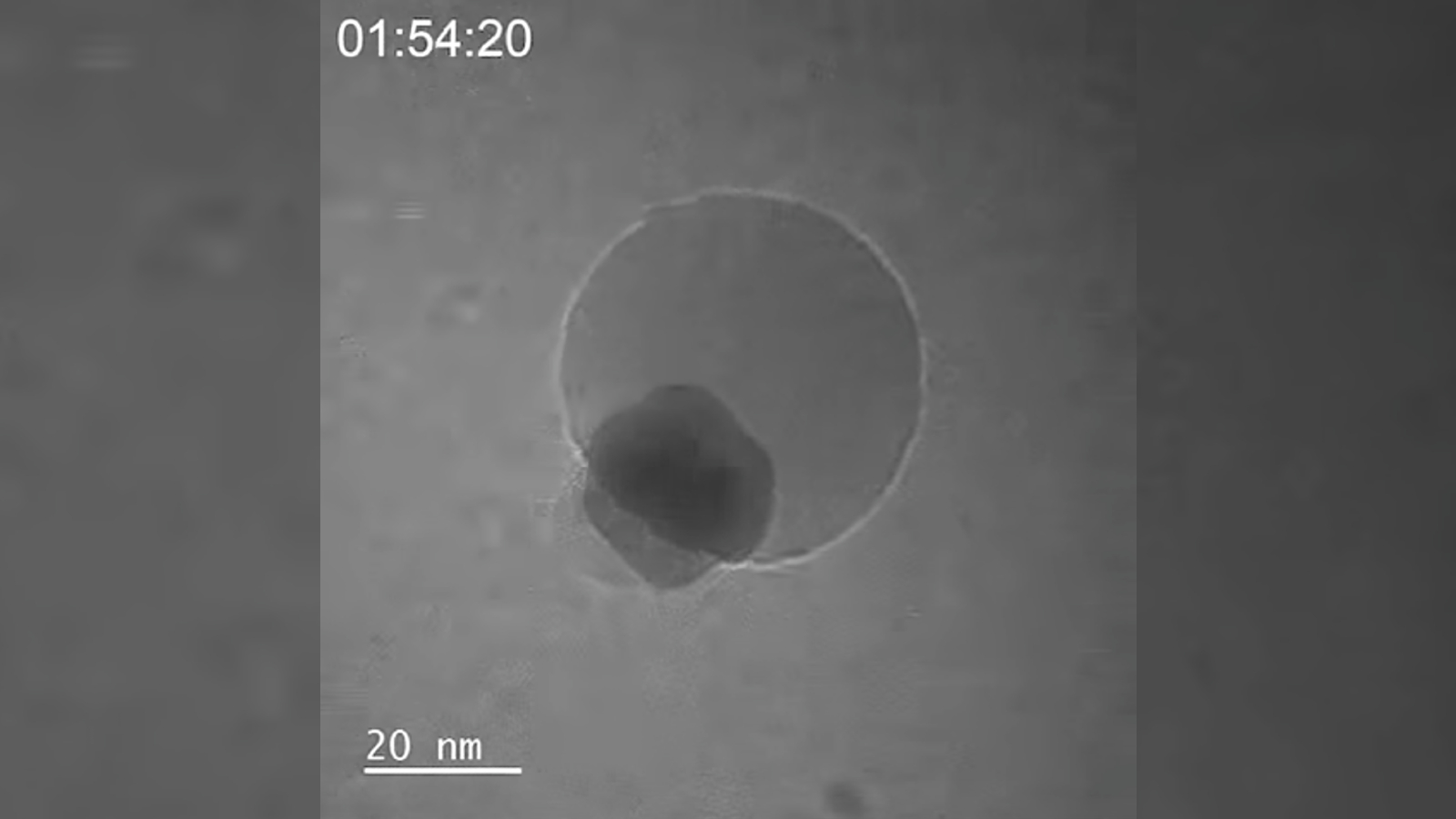

For the first time, researchers have captured nanoscale video footage of hydrogen and oxygen atoms combining into water out of "thin air" — thanks to a rare metal catalyst. The super-efficient reaction, which could one day help astronauts make water in space, also produced the smallest bubble of water ever seen, researchers say.

The video was part of a new study, published Sept. 27 in the journal PNAS, in which researchers tested how palladium catalyzes a reaction between hydrogen and oxygen gases to create water in standard lab conditions. The team studied this reaction with a new type of monitoring apparatus that captured the process in extraordinary detail.

"We think it might be the smallest bubble ever formed that has been viewed directly," study lead author Yukun Liu, a materials scientist at Northwestern University in Illinois, said in a statement. "Luckily, we were recording it, so we could prove to other people that we weren't crazy."

The team induced the reaction using a special ultra-thin glassy membrane that holds gas molecules within honeycomb-shaped "nanoreactor" chambers. This means the tests can be viewed in real time using electron microscopes, enabling the researchers to learn more about how the reaction works.

Researchers from the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental Center (NUANCE) pioneered this novel technique in a study published in January.

Related: New reactor could more than triple the yield of one of the world's most valuable chemicals

Researchers have known since the 1900s that palladium, a silver-white rare metal similar in appearance to platinum, can catalyze a dry reaction between hydrogen and oxygen, researchers wrote. However, until now, it was unclear exactly how the reaction worked.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new study revealed that the gaseous atoms first squeeze between the palladium atoms, which are arranged in a square lattice. This expands the lattice and enables water droplets to form on the catalyst's surface. The team also found that the process can be sped up by adding hydrogen atoms to the palladium first, because they are smaller than oxygen atoms. This enables the palladium lattice to expand before the oxygen is added, creating bigger gaps for the larger atoms to fit more readily inside.

The team believes that a scaled-up version of the reaction could be used to create water for astronauts in space or in colonies on other planets. The researchers compared it to a scene from the sci-fi film "The Martian" starring Matt Damon, in which a stranded astronaut makes water on Mars by burning rocket fuel and combining it with oxygen from his suit.

"Our process is analogous, except we bypass the need for fire and other extreme conditions," study co-author Vinayak Dravid, director of the NUANCE Center, said in the statement. "We simply mixed palladium and gases together."

Palladium is an expensive and rare material, costing upwards of $1,000 per ounce. This is largely because it can catalyze many other chemical reactions and is used in a wide range of technologies. As a result, creating a water-generating device for astronauts could be extremely costly.

However, the researchers argued that it would be worth the expense in the long run.

"Palladium might seem expensive, but it's recyclable," Liu said. "Our process doesn't consume it. The only thing consumed is gas, and hydrogen is the most abundant gas in the universe."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.