Why does paper tear more easily when it's wet?

Paper gets flimsy when wet due to its chemical structure, primarily its hydrogen bonds.

If you've ever spilled a drink over the paperwork on your desk or accidentally placed your dinner napkin on a damp surface, you know how frustratingly flimsy paper gets when it's wet. Even the smallest drop of water seems to weaken that pristine sheet forever. But why is paper so much easier to tear when it's wet?

The answer comes down to the paper's chemical structure.

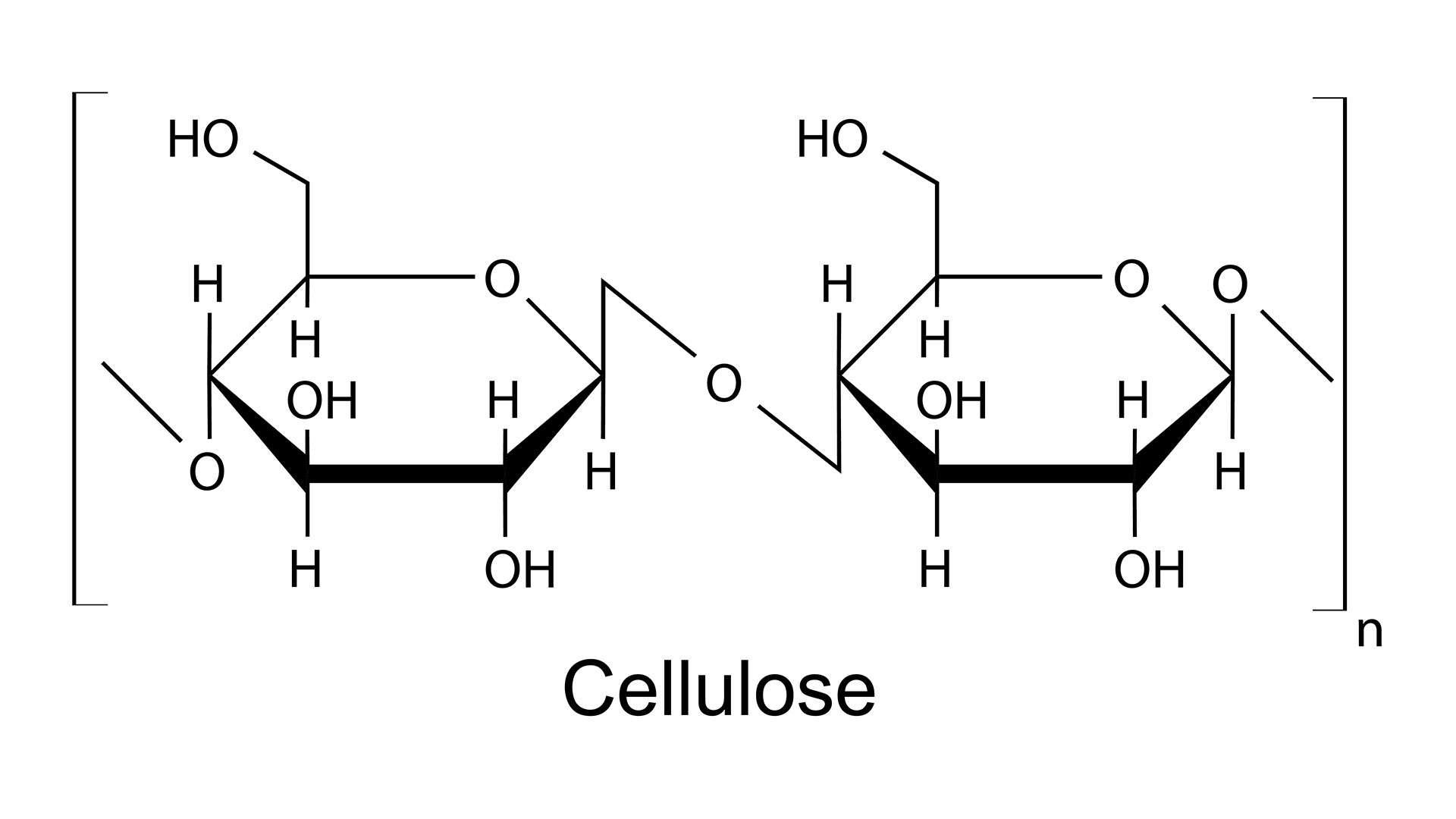

"At the heart of it, paper is just cellulose fibers — natural polymer molecules from wood — woven around each other to form a sheet," Charlotte Scott-Parker, a research and development specialist at James Cropper Paper Mill in the U.K., told Live Science. "Within a normal sheet of paper, these fibers are interlocked with each other through little hook-like irregularities on the individual strands of cellulose, but they're also bonded between each other by hydrogen bonds."

Hydrogen bonds are one of the most important interactions in chemistry; without them, life couldn't exist. Certain chemical bonds can behave a bit like a magnet, with one end slightly positive and the other slightly negative. As with true magnets, opposites attract, so the positive end of one molecule is drawn toward the negative end of another nearby molecule, and this attraction holds the two together.

Related: How many times can you fold a piece of paper in half?

Molecules that contain oxygen bonded to hydrogen — including water, H2O — are particularly prone to this type of interaction, known as hydrogen bonding. And it just so happens that the cellulose polymer, a strand of repeating chemical units, is covered with oxygen-hydrogen handles down the entire length of the fiber.

"When you tear a piece of dry paper, basically you just need to overcome all the intermolecular forces, the friction, and the fiber entanglements," Marko Kolari, a research and development fellow at Kemira, a pulp and paper chemicals company in Finland, told Live Science. "If you make paper wet, the fiber matrix swells; the fibers begin to detach; and it starts to lose strength, so it's easier to tear."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

On a chemical level, the water disrupts the vital hydrogen bonds holding the cellulose fibers together, Scott-Parker said. Because water also contains that all-important oxygen-hydrogen bond, it begins to form its own hydrogen bonds with the cellulose, blocking the other fibers from binding. With fewer interactions between the individual cellulose polymers, it becomes easier to separate the fibers, so less force is needed to tear the paper.

But not all paper is created equal. Think about all of the paper products you use daily — toilet paper, paper towels, newspapers, printer paper, cardboard, and more. "The cellulose fiber is almost identical in all these products, and yet they are so different and diverse in their properties," Kolari said. The way these different grades respond to water comes down to the extra additives included during the papermaking process, he added.

The paper industry has myriad chemical tricks to enhance the properties of paper products, and one of the most important features manufacturers focus on is strength.

"If you want a strong material like a packaging box, we need to strengthen the fiber matrix, and we do this using dry strength additives like potato starch," Kolari said. A layer of this natural compound is applied to the surface of the paper as a gel and forms a toughened barrier around the interwoven cellulose fibers when dried. This sturdy starch surface acts as scaffolding and gives the paper a huge boost in strength.

But even toughened cardboard isn't immune to the damaging effects of moisture. "Starch dissolves in water," Kolari said, "so if it gets wet, you lose that added strength again really rapidly."

Victoria Atkinson is a freelance science journalist, specializing in chemistry and its interface with the natural and human-made worlds. Currently based in York (UK), she formerly worked as a science content developer at the University of Oxford, and later as a member of the Chemistry World editorial team. Since becoming a freelancer, Victoria has expanded her focus to explore topics from across the sciences and has also worked with Chemistry Review, Neon Squid Publishing and the Open University, amongst others. She has a DPhil in organic chemistry from the University of Oxford.