What is the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone?

Here's a look at one of the most radioactive places in the world.

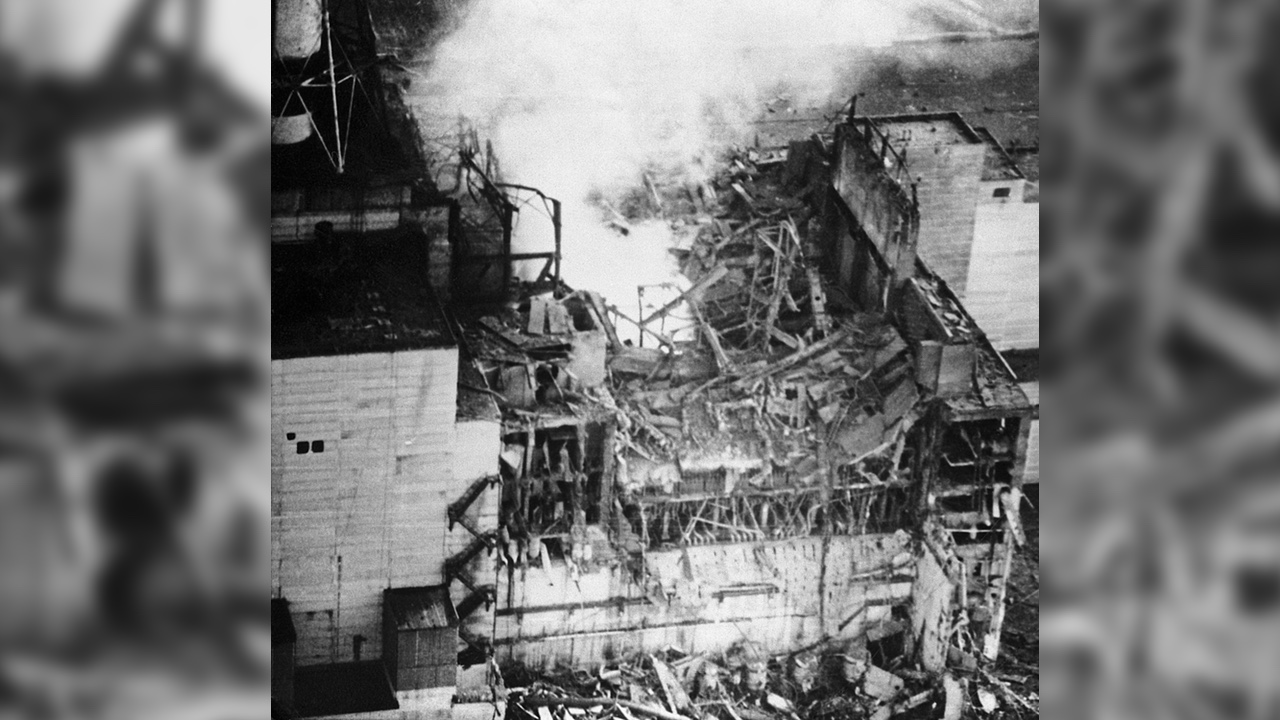

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is one of the most radioactive places in the world. On April 26, 1986, a disastrous meltdown at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine (in the former USSR) led to two enormous explosions that blew the 2,000-ton (1,800 metric tons) lid off one of the plant's reactors, blanketing the region with reactor debris and its radioactive fuel. The explosion released into the atmosphere 400 times more radiation than was produced by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, and nuclear fallout rained down far and wide across Europe, according to a report by the European Parliament.

On May 2, 1986, a Soviet Union commission officially declared an off-limits area around the disaster and called it the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. The zone includes an area of roughly 1,040 square miles (2,700 square kilometer) around the 18.6 mile (30 km) radius of the plant; the area was considered the most severely irradiated environment and was cordoned off to anyone but government officials and scientists, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. By April 27 (the day after the explosion), officials had already evacuated the nearby city of Pripyat, but fresh orders in May were given to evacuate everyone who remained within the exclusion zone. Over the following weeks and months, around 116,000 people would be relocated from inside the exclusion zone. This number continued to grow, reaching a total of around 200,000 people before the end of the evacuation, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Related: 5 Weird things you didn't know about Chernobyl

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, during the first year of its existence, the 18.6 mile (30 km) mile exclusion zone was further split into three distinct regions:

— The inner exclusion zone: the high-radiation region within a 6.2 mile (10 km) radius of the plant from which the population was to be evacuated and permanently forbidden reentry.

— The zone of temporary evacuation: a moderately irradiated region to which the public could return once the radiation had decayed to safe levels.

— The zone of rigorous monitoring: a sporadically irradiated region from which children and pregnant women were moved into less irradiated areas in the immediate aftermath of the disaster.

The exclusion zone has expanded in subsequent years. When the Ukranian exclusion zone is added together with the neighboring Belarusian exclusion zone, the combined area makes up an approximate 1,550 square miles (4,000 square kilometers), according to the European Radioecology Exchange Alliance.

At the beginning of 2022, increasing tensions between Russia and NATO over Ukraine's potential membership to the western military alliance has also led to an increased guard presence inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, according to Sky News. The region, which lies close to Ukraine's northern border with Russia's ally Belarus and straddles the most direct route between it and Ukraine’s capital, Kiev, was stationed with 7,500 more border guards between December 2021 and February 2022.

How dangerous is the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone?

More than 100 radioactive elements were released into the atmosphere immediately after the disaster, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The most dangerous of them were isotopes of iodine, strontium and cesium, which have respective radioactive half-lives (the period of time it takes for half of the material to decay) of 8 days, 29 years and 30 years. The majority of the elements released were short-lived (meaning their half-lives are no more than a few weeks or even days), but the long half-lives of strontium and cesium mean they are still present in the area. At low levels, iodine can cause thyroid cancer; strontium leukemia; and cesium has especially damaging effects on the liver and spleen, according to the IAEA.

Still other radioactive elements released in the explosion are much longer lived, such as plutonium-239 which has a half-life of 24,000 years. And so despite the entire Chernobyl Exclusion Zone being much less radioactive today than it was in the days immediately following the disaster, the longest-lived radioactive materials inside the zone could still take thousands of years for half of their atomic nuclei to decay, according to the National Geographic. Radiation readings taken within the zone show that its more contaminated areas still contain dangerous amounts of radiation.

By the end of 1986, the USSR had hastily built a concrete sarcophagus around the exploded reactor to contain the remaining radioactive material, according to Science. Then, in 2017, officials built a larger, second enclosure, this one made of steel, around the sarcophagus called the New Safe Confinement structure, which was 843 feet (257 meters) wide, 531 feet (162 m) long and 356 feet (108 m) tall. This enclosure was designed to completely enclose the reactor and its sarcophagus for 100 years, according to World Nuclear News. Even so, much of the nuclear fuel inside the reactor is still smoldering, leaving scientists monitoring the site concerned that the material could explode again, Live Science previously reported. If it were to explode, the force could cause the sarcophagus to collapse, burying the nuclear material under even more rubble.

A further source of concern for scientists observing the exclusion zone is the irradiated trees in the woodlands surrounding the plant. Not long after the explosion, many of the trees closest to the power plant absorbed so much radiation that they turned a bright orange before dying, earning the region the nickname of the "Red Forest." The dead trees were eventually bulldozed and buried, but a lot of surviving plant life absorbed large amounts of dangerous radionuclides, which in the event of a forest fire could be sent aloft as inhalable aerosols.

Life inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

Today, the exclusion zone is filled with a variety of wildlife species that have flourished in humanity's absence. Wolves, wild boars, beavers, moose, eagles, deer, lynx and bears have all thrived in the zone’s thick woodlands. Packs of dogs, the now feral descendants of the region's abandoned pets, also roam the zone, according to the BBC. British ecologists studying the region have also found that the population of the Przewalski's horse, an endangered wild horse species originally from Mongolia has exploded inside the zone, they reported in 2016 in The Biologist.

Despite mostly appearing in good health, some of the zone's animals carry high levels of cesium in their bodies, and birds in the area are 20 times more likely to have genetic mutations, according to a 2001 study in the journal Biological Conservation. Insects were among the hardest hit by the sudden spike in radiation levels, with significant reductions in their populations in the most irradiated regions, according to a 2009 study in the journal Biology Letters.

Do people live inside the exclusion zone?

The zone is not completely without people, either. In the years following the disaster, roughly 200 residents, known as "samosely," illegally returned to their evacuated villages to eke out an existence in their once abandoned homes. The samosely are mostly retired individuals, and they survive primarily through subsistence farming and care packages delivered by visitors, according to ABC News.

How to visit the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

Since 2011, when the exclusion zone was deemed safe to visit by site managers, growing numbers of tourists have also flocked to visit the area. While parts of the zone remain dangerously radioactive, visiting is relatively safe as long as tourists are led by experienced guides, according to Responsible Travel. The zone itself is a little over two hours drive from Kiev. Visits take one day, starting and ending with passages through official checkpoints to measure exposure to radiation, according to the State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management.

Those who work inside the zone, as scientists, administrators or tour guides, have been known to refer to themselves as "stalkers" after the Andrei Tarkovsky film of the same name. The Soviet science-fiction movie (which was released seven years before the disaster in 1979) tells of an expedition led by a stalker into a reality-warped restricted site known as the "Zone," where there is said to be a room which grants a person their innermost desires. Curiosity about the exclusion zone was also generated by a 2019 HBO mini-series based on the Chernobyl disaster; and Live Science previously reported that visitation rates jumped by 30-40% after the series aired.

Additional resources

- The latest news about the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant can be found on their website.

- Answers to long-standing questions about the health effects of the Chernobyl disaster according to the World Health Organization.

- Answers to frequently asked questions about the Exclusion Zone can be found on the International Atomic Energy Agency's website.

- Insights into Chernobyl's growing wildlife populations can be found on the UN Environmental Programme's website.

Bibliography

Serhii Plokhy, Chernobyl: The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe, Basic Books, 2018

Svetlana Alexievich, Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster, Picador Books, 1997

Katie Canales, Photos show what daily life is really like inside Chernobyl's exclusion zone, Business Insider, April 20, 2020.

Chris Baraniuk, The guards caring for Chernobyl's abandoned dogs, BBC Future, April 23, 2021.

Neel Dhanesha, How nature has taken over Chernobyl, Popular Science, July 21 2021.

Jane Braxton Little, Forest fires are setting Chernobyl's radiation free, The Atlantic, August 10 2020

Adam Tooze, Chartbook #68 Putin's Challenge to Western hegemony - the 2022 edition, January 12 2022.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.