The nation's first fully homegrown Mars mission, Tianwen-1, arrived in orbit around the Red Planet Wednesday (Feb. 10), according to Chinese media reports.

The milestone makes China the sixth entity to get a probe to Mars, joining the United States, the Soviet Union, the European Space Agency, India and the United Arab Emirates, whose Hope orbiter made it to the Red Planet just yesterday (Feb. 9).

And Wednesday's achievement sets the stage for something even more epic a few months from now — the touchdown of Tianwen-1's lander-rover pair on a large plain in Mars' northern hemisphere called Utopia Planitia, which is expected to take place this May. (China doesn't typically publicize details of its space missions in advance, so we don't know for sure exactly when that landing will occur.)

Related: Here's what China's Tianwen-1 Mars mission will do

See more: China's Tianwen-1 Mars mission in photos

Book of Mars: $22.99 at Magazines Direct

Within 148 pages, explore the mysteries of Mars. With the latest generation of rovers, landers and orbiters heading to the Red Planet, we're discovering even more of this world's secrets than ever before. Find out about its landscape and formation, discover the truth about water on Mars and the search for life, and explore the possibility that the fourth rock from the sun may one day be our next home.

An ambitious mission

China took its first crack at Mars back in November 2011, with an orbiter called Yinghuo-1 that launched with Russia's Phobos-Grunt sample-return mission. But Phobos-Grunt never made it out of Earth orbit, and Yinghuo-1 crashed and burned with the Russian probe and another tagalong, the Planetary Society's Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment.

Tianwen-1 (which means "Questioning the Heavens") is a big step up from Yinghuo-1, however. For starters, this current mission is an entirely China-led affair; it was developed by the China National Space Administration (with some international collaboration) and launched atop a Chinese Long March 5 rocket on July 23, 2020.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tianwen-1 is also far more ambitious than the earlier orbiter, which weighed a scant 254 lbs. (115 kilograms). Tianwen-1 tipped the scales at about 11,000 lbs. (5,000 kg) at launch, and it consists of an orbiter and a lander-rover duo.

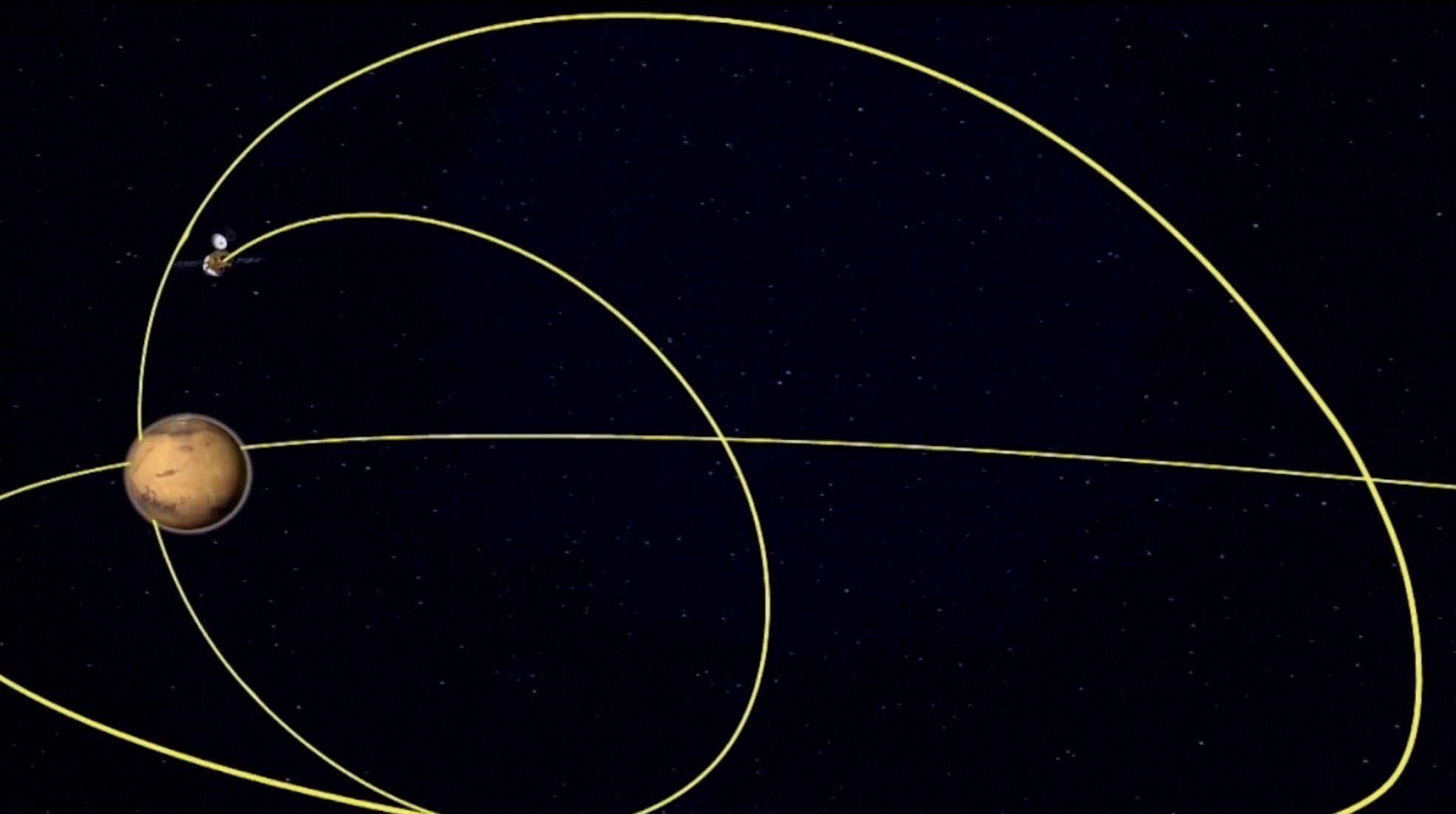

These craft will take Mars' measure in a variety of ways. The orbiter, for example, will study the planet from above using a high-resolution camera, a spectrometer, a magnetometer and an ice-mapping radar instrument, among other scientific gear.

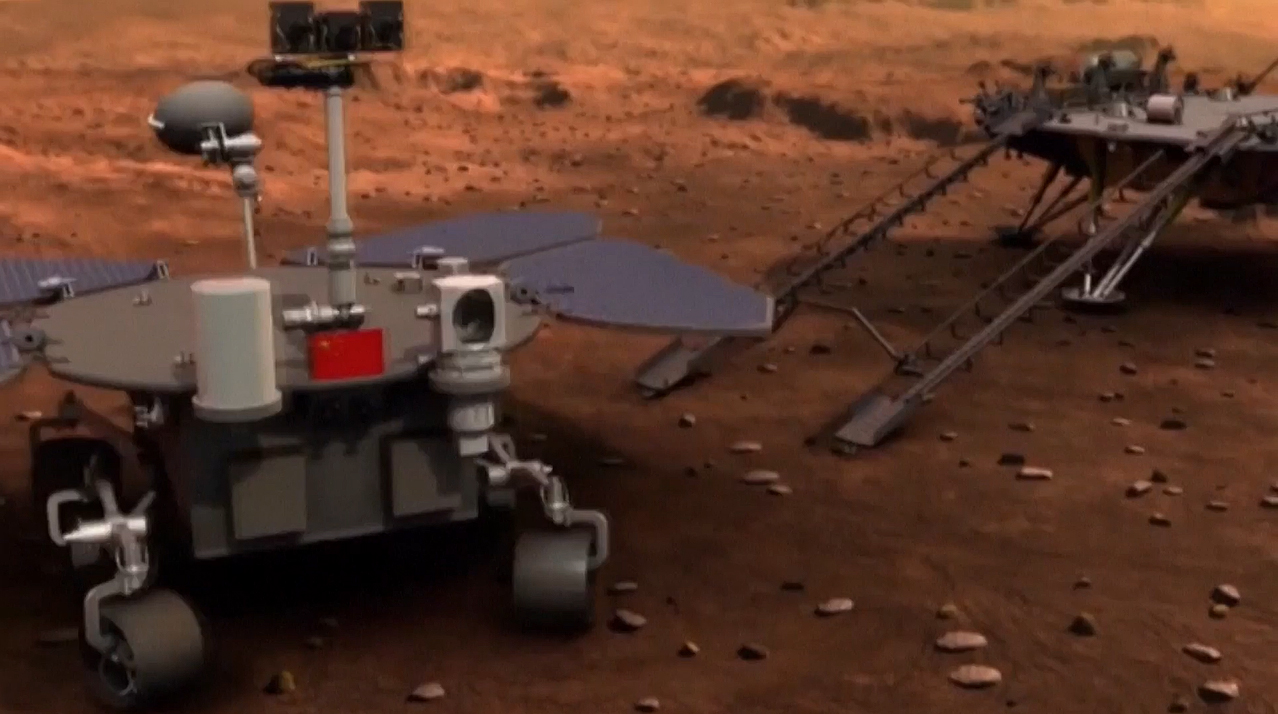

The orbiter will also relay communications from the rover, which sports an impressive scientific suite of its own. Among the rover's gear are cameras, climate and geology instruments and ground-penetrating radar, which will hunt for pockets of water beneath Mars' red dirt.

Occupy Mars: History of robotic Red Planet missions (infographic)

"On Earth, these pockets can host thriving microbial communities, so detecting them on Mars would be an important step in our search for life on other worlds," the Planetary Society wrote in a description of the Tianwen-1 mission.

The lander, meanwhile, will serve as a platform for the rover, deploying a ramp that the wheeled vehicle will roll down onto the Martian surface. The setup is similar to the one China has used on the moon with its Chang'e 3 and Chang'e 4 rovers, the latter of which is still going strong on Earth's rocky satellite.

If the Tianwen-1 rover and lander touch down safely this May and get to work, China will become just the second nation, after the United States, to operate a spacecraft successfully on the Red Planet's surface for an appreciable amount of time. (The Soviet Union pulled off the first-ever soft touchdown on the Red Planet with its Mars 3 mission in 1971, but that lander died less than two minutes after hitting the red dirt.)

The Tianwen-1 orbiter is scheduled to operate for at least one Mars year (about 687 Earth days), and the rover's targeted lifetime is 90 Mars days, or sols (about 93 Earth days).

Bigger things to come?

Tianwen-1 will be just China's opening act at Mars, if all goes according to plan: The nation aims to haul pristine samples of Martian material back to Earth by 2030, where they can be examined in detail for potential signs of life and clues about Mars' long-ago transition from a relatively warm and wet planet to the cold desert world it is today.

NASA has similar ambitions, and the first stage of its Mars sample-return campaign is already underway. The agency's Perseverance rover will touch down inside the Red Planet's Jezero Crater next Thursday (Feb. 18), kicking off a surface mission whose top-level tasks include searching for signs of ancient Mars life and collecting and caching several dozen samples.

Perseverance's samples will be hauled home by a joint NASA-European Space Agency campaign, perhaps as early as 2031.

So we have a lot to look forward to in the coming days and weeks, and many reasons to keep our fingers crossed for multiple successful Red Planet touchdowns.

"More countries exploring Mars and our solar system means more discoveries and opportunities for global collaboration," the Planetary Society wrote in its Tianwen-1 description. "Space exploration brings out the best in us all, and when nations work together everyone wins."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.