Chinese rocket will crash to Earth on Nov. 5. Here's what we know.

This is the fourth time in two years that a Long March 5B booster has crashed back to Earth in an uncontrolled reentry.

The core stage of yet another Chinese Long March 5B rocket is set to tumble uncontrollably back to Earth this week after delivering the third and final module to China's fledgling space station.

The roughly 25-ton (23 metric tons) rocket stage, which launched Oct. 31 to deliver the Mengtian laboratory cabin module to the Tiangong space station, is predicted to reenter Earth's atmosphere on Saturday, Nov. 5 at 11:51 p.m. EDT, give or take 14 hours, according to researchers at The Aerospace Corporation's Center for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies.

Exactly where the rocket will land is unknown, but the possible debris field includes the U.S., Central and South America, Africa, India, China, Southeast Asia and Australia, according to The Aerospace Corporation, a U.S. government-funded nonprofit research center based in California. This is the fourth time in two years that China has disposed of its rockets in an uncontrolled manner. The previous crash landings saw metallic objects rain down upon villages in the Ivory Coast, debris land in the Indian Ocean near the Maldives, and rocket chunks crash dangerously close to villages in Borneo.

Related: NASA set to launch 2 rockets into the northern lights

The first stage of a rocket, its booster, is usually the bulkiest and most powerful section — and the least likely to completely burn up upon reentry. There are ways to get around this issue. Engineers try to aim rockets so that their booster sections don't escape into orbit, plopping them down harmlessly into the ocean instead. If boosters do make orbit, some are designed to fire a few extra bursts from their engines to steer them back into a controlled reentry.

But the Long March 5B booster engines cannot restart once they have stopped, dooming the massive booster to spiral around Earth before landing in an unpredictable location.

China has insisted that uncontrolled reentries are common practice and has dismissed concerns about potential damage as "shameless hype." In 2021, Hua Chunying, then-spokesperson for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accused Western reporting of bias and "textbook-style double standards" in its coverage of China's falling rockets. For instance, in March 2021, debris from a falling SpaceX rocket smashed into a farm in Washington state — an event Hua claims Western news outlets covered positively and with the use of "romantic words." A year later, in August 2022, a second set of SpaceX debris landed on a sheep farm in Australia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The odds that someone will be harmed by the falling rocket are small (ranging from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 230) and the risk to single individuals are even lower (between 1 in 10 trillion and 1 in 6 trillion), according to The Aerospace Corporation. Nonetheless, as the rocket's debris path fits over roughly 88% of the world's population, it does put the odds of harm far above the internationally accepted casualty risk threshold for uncontrolled reentries of 1 in 10,000.

"Spacefaring nations must minimize the risks to people and property on Earth of reentries of space objects and maximize transparency regarding those operations," NASA Administrator Bill Nelson wrote in a statement after the 2021 Long March 5B crash landing. "It is clear that China is failing to meet responsible standards regarding their space debris."

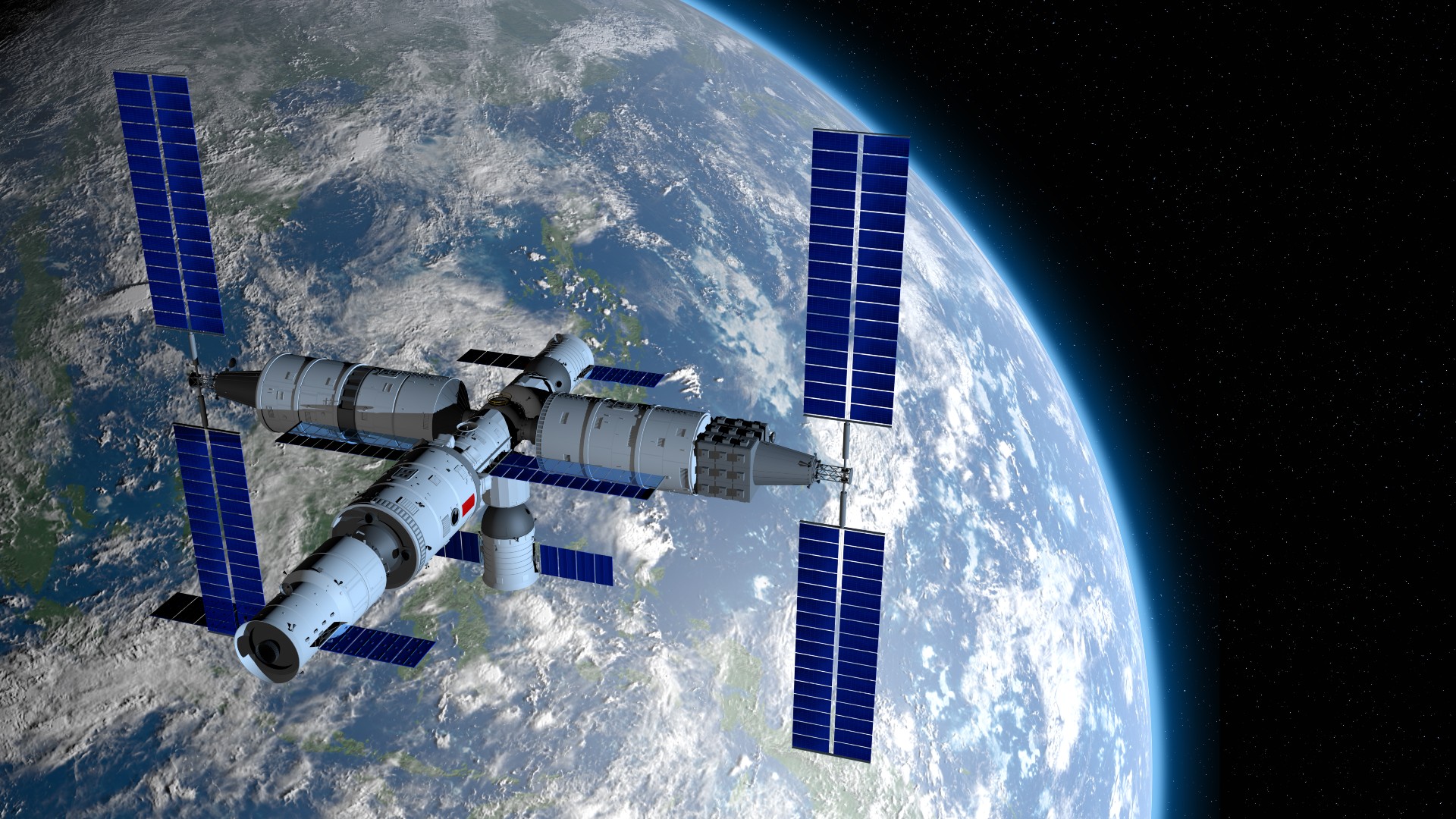

The T-shaped Tiangong space station, whose mass is roughly one-quarter that of the International Space Station, is expected to remain in low Earth orbit for at least 10 years. Its rotating crews of three astronauts will use the station to perform experiments and tests of new technologies, such as ultracold atomic clocks.

In recent years, China has been ramping up its space presence to catch up with the U.S. and Russia, having landed a rover on the far side of the moon in 2019 and retrieved rock samples from the moon's surface in 2020. China has also declared that it will establish a lunar research station on the moon's south pole by 2029.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.