Archaeologists find vast network of Amazon villages laid out like the cosmos

Laser and satellite technology revealed more than 35 villages.

Billions of lasers shot from a helicopter flying over the Brazilian Amazon Rainforest have detected a vast network of long-abandoned circular and rectangular-shaped villages dating from 1300 to 1700, a new study finds.

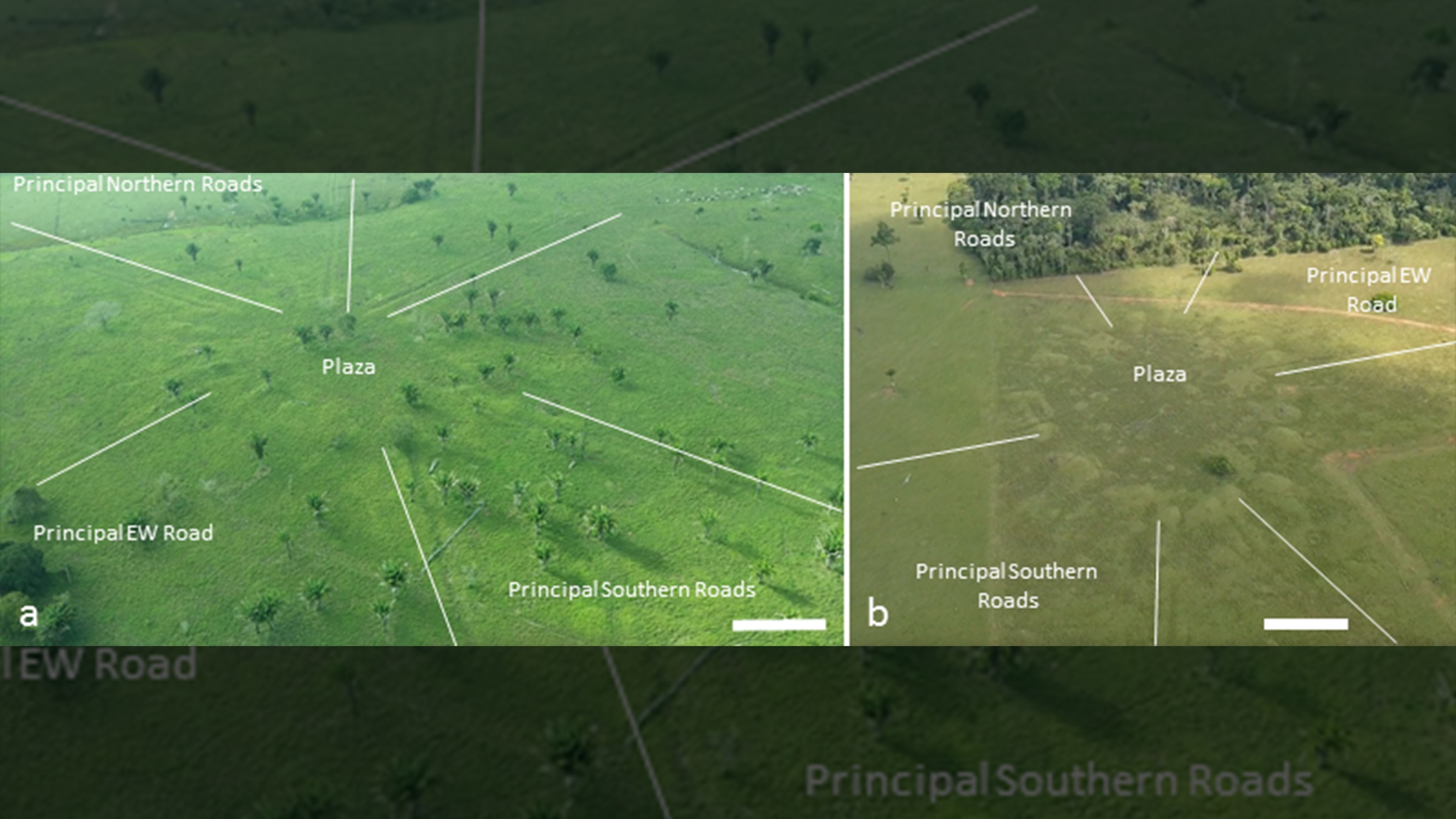

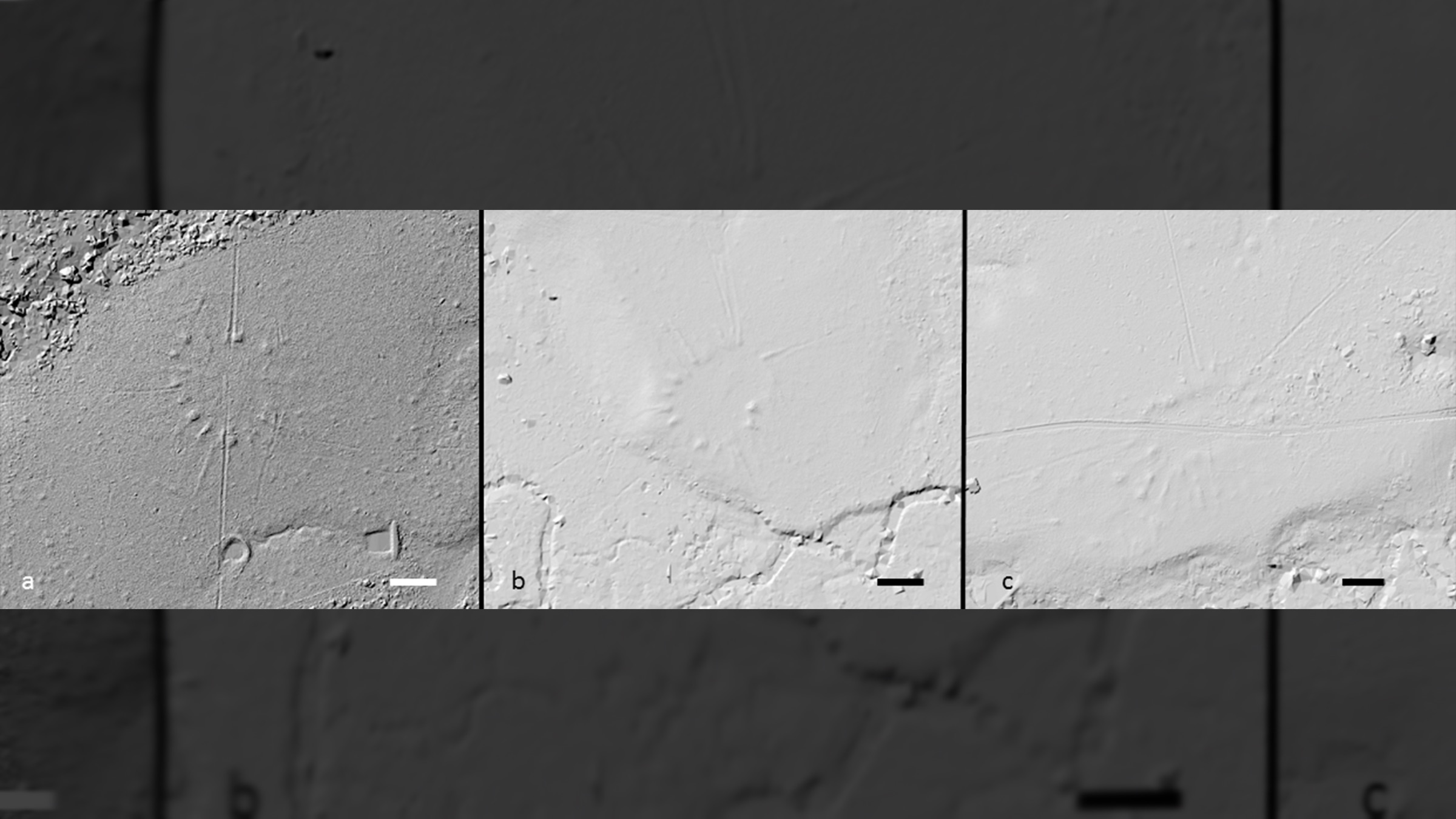

The round villages all had remarkably similar layouts, with elongated mounds circling a central plaza, like marks on a clock.

"These latter elongated mounds, when seen from above, look like the rays of the sun, which gives them the common name of 'Sóis,'" the Portuguese word for "suns," the researchers wrote in the study.

Related: Amazon photos: Trees that dominate the rainforest

The discovery is part of a new archaeological focus on the pre-Columbian Amazon. Within the past 20 years, researchers have learned that the rainforest's southern rim was home to a great diversity of soil-sculpting cultures that engineered the landscape before the Europeans arrived. Within the past decade, scientists have uncovered the remnants of so-called "mound villages," which are shaped as circles or rectangles, and connected by road networks.

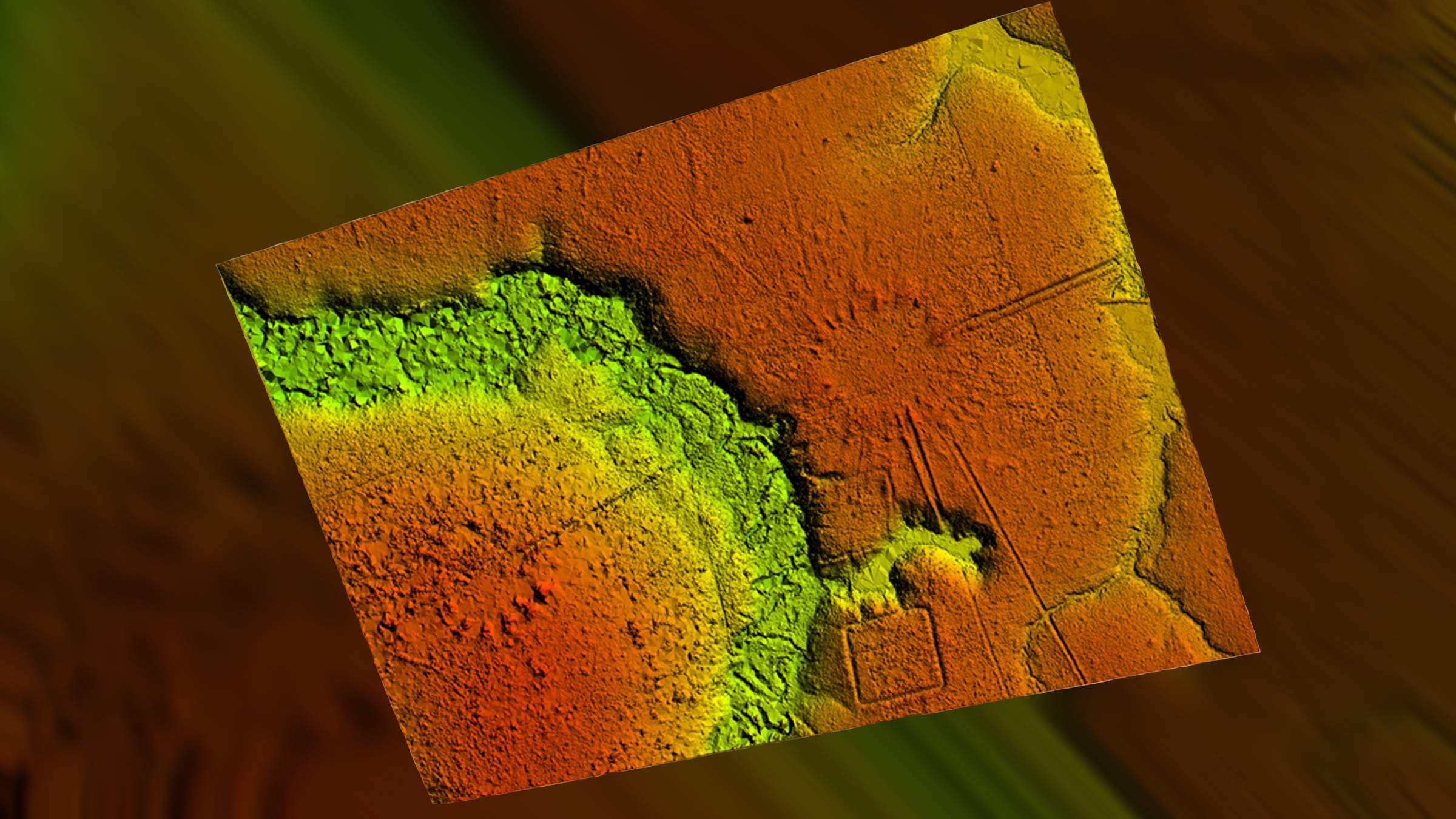

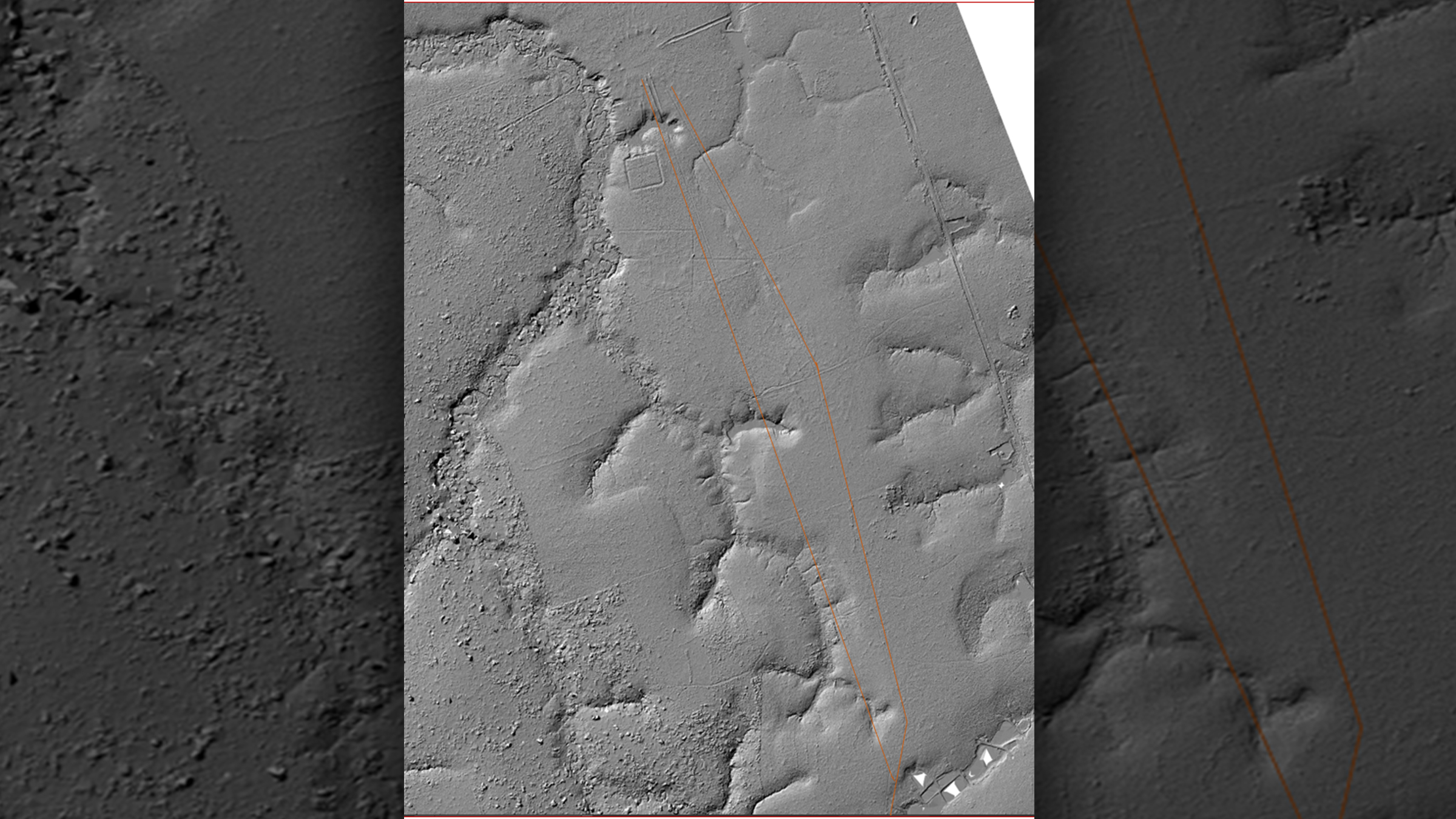

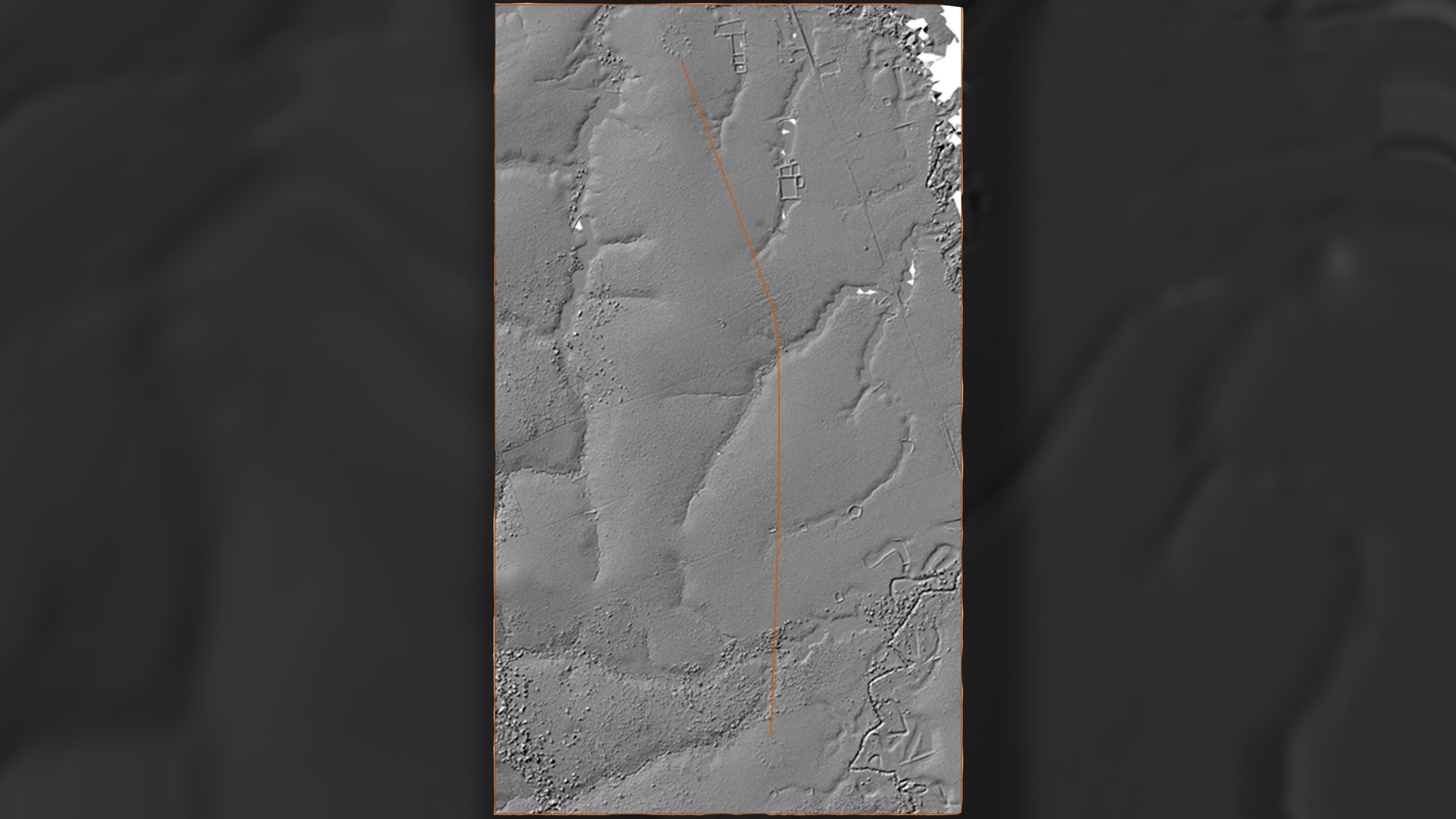

Archaeologists, however, had yet to look for mound villages in the Brazilian state of Acre, so an international group of researchers teamed up to survey the area with lidar — or light detection and ranging. With this technique, billions of lasers shot from overhead (in this case, from a helicopter) penetrate the rainforest's canopy and map the landscape below.

The lidar survey, combined with satellite data, revealed a remarkable 25 circular mound villages and 11 rectangular mound villages, the researchers said. Another 15 mound villages were so poorly preserved, they could not be categorized as either circular or rectangular, the team added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The circular mound villages had an average diameter of 282 feet (86 meters), while the rectangular villages tended to be smaller, with an average length of 148 feet (45 m). Further analysis of the "sun" villages revealed they had carefully planned roads; each circular mound village had two "principal roads" that were wide and deep (up to 20 feet, or 6 m, across) with high banks, and smaller "minor roads" that led to nearby streams.

Most of the villages were close to each other — just about 3 miles (4.4 km) apart, the researchers found. The principal roads often connected one village to another, creating a vast community network in the rainforest, the researchers said.

The distinctive and consistent way Indigenous people arranged these villages suggests that they had specific social models for the way they organized their communities, the researchers said. It's even possible that this configuration was meant to represent the cosmos, they noted.

The intricate road system, however, "is hardly a surprise for Amazonian archaeologists," the researchers wrote in the study. "Early historical accounts attest to the ubiquity of road networks across the Amazon. They are mentioned since the 16th-century account of [the Spanish Dominican missionary] Friar Gaspar de Carvajal, who observed wide roads leading from the riverine villages to the interior." Later, in the 18th century, Col. Antonio Pires de Campos, "described a vast population inhabiting the region, with villages connected by straight, wide roads that were constantly kept clean," the researchers added.

Little is known about the culture practiced by the people in these mound villages. But preliminary research suggests that this culture's ceramics were "cruder" than those of the culture that preceded them, known as the Geoglyphs, who lived in that region from about 400 B.C. to A.D. 950.

The study was published in April in the Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, and was just featured on Channel 4's "Jungle Mystery: Lost Kingdoms of the Amazon," in the U.K., which also featured other ancient findings from the Amazon, including a sprawling, 8-mile-long 'canvas' of rock art in Colombia dating to the last ice age.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.