Closest black hole to Earth discovered lurking in our 'cosmic backyard'

How the binary system formed is a mystery

Astronomers have discovered the nearest known black hole to Earth, and it’s twice as close as the previous record holder.

The space-time singularity, named Gaia BH1, is 1,566 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus and is roughly 10 times more massive than our sun. It’s close enough to our planet to be considered "in our cosmic backyard," researchers said in a statement.

Gaia BH1 is not alone; it’s part of a binary system with a sun-like star that orbits it at around the same distance as Earth orbits the sun. The system, which was described in a Nov. 4 study published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, is the first of its kind ever observed in the Milky Way.

Related: Are black holes wormholes?

"While there have been many claimed detections of systems like this, almost all these discoveries have subsequently been refuted," lead author Kareem El-Badry, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts and the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, said in the statement. "This is the first unambiguous detection of a sunlike star in a wide orbit around a stellar-mass black hole in our galaxy."

Black holes start out as large stars with a mass roughly five to 10 times that of the sun. As larger stars approach the ends of their lives, they fuse heavier and heavier elements, such as silicon or magnesium, inside their burning cores. But once this fusion process begins forming iron, the star is locked on a path to violent self-destruction.

Iron requires more energy to fuse than it releases, and the star can no longer withstand the immense gravitational forces generated by its enormous mass. It explodes outwards before collapsing in on itself, packing first its core, and later all the matter close to it, into a point of infinitesimal dimensions and infinite density — a singularity. Beyond a boundary called the event horizon, nothing — not even light — can escape the new black hole’s gravitational pull.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

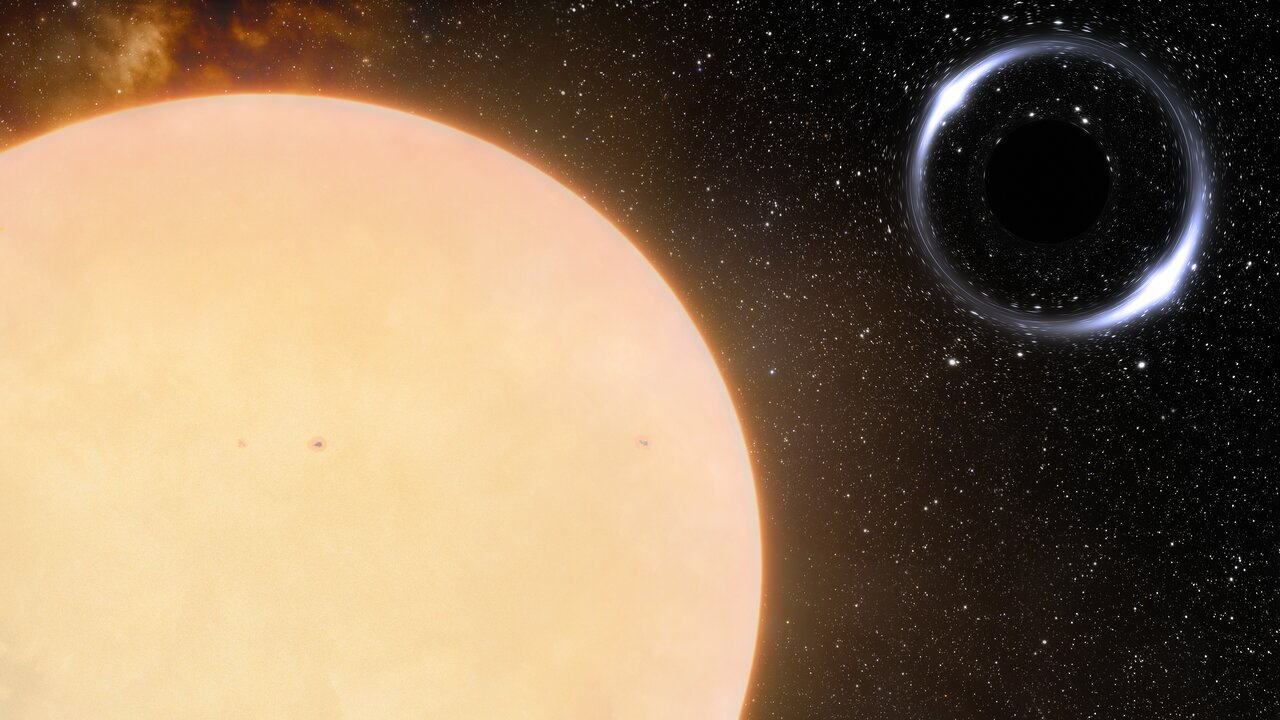

Feeding black holes are visible as a dark heart surrounded by a ring of fuzzy, warped light. This halo comes from matter that is slowly being stripped and shredded from nearby stars, planets and nebulae.

But not all black holes are feeding, and finding these dormant monsters among the roughly 100 million stellar-mass black holes estimated to be lurking in the Milky Way requires an elaborate strategy.

To zero-in on the nearby black hole, the researchers turned to the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft that has been mapping the positions and movements of the Milky Way’s roughly 2 billion stars. By poring through Gaia’s data, the astronomers found one star that appeared to have a distinct wobble — a slight limp in the usually smooth path of its trajectory. The researchers suspected that the mysterious wobble came from the invisible tugs of a black hole.

To confirm this, the scientists turned to ground-based telescopes such as Magellan Clay and MPG/ESO in Chile and Gemini North and Keck 1 in Hawaii. Detailed observations revealed that a giant, unseen object was indeed yanking at the star.

"Our Gemini follow-up observations confirmed beyond reasonable doubt that the binary contains a normal star and at least one dormant black hole," El-Badry said.

The system is also interesting because the black hole may have originated from a star 20 times more massive than our sun. Normally, such behemoths balloon outwards at the end of their lives, consuming everything in their path, before collapsing inwards to form a black hole.

This process should have consumed the black hole’s star companion, or at least yanked it into a much tighter orbit, according to the researchers, and yet it’s still mysteriously intact and orbiting at a fair distance. Finding out how this happened is the astronomers’ next challenge.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.