This mysterious comet's super-bright outbursts have astronomers puzzled

Comet 29P behaves in such an unpredictable way that professional astronomers don't know what to do with it.

One of the strangest comets in the solar system has been erupting with unpredictable bright outbursts since late September and nobody knows why. An international observation campaign comprising amateur and professional astronomers alike, and even the famous Hubble Space Telescope, now wants to crack the mystery.

Comet 29P is a mind-boggling object. More than 37 miles (60 kilometers) across, it is one of the largest comets known — about as big as the famous Hale-Bopp that streaked the sky in the 1990s. It is one of only a handful of comets known as Centaurs, which orbit the sun between Saturn and Jupiter, slowly making their way through what astronomers call a gateway, waiting to eventually be flung by Jupiter's gravity closer to the sun (or out of the solar system entirely). And 29P brightens up periodically with powerful eruptions that make it the second most active body in the solar system after Jupiter's moon Io. But why is it erupting? Nobody knows.

But despite its curious nature, most observations of Comet 29P until recently came from amateur astronomers.

"You can't predict when the comet erupts," Richard Miles, an amateur astronomer and former research scientist in hydrocarbon chemistry who is currently the head of the Asteroids and Remote Planets Section of the British Astronomical Association, told Space.com. "For professional astronomers to get telescope time to do systematic monitoring is quite difficult. But amateurs have their telescopes in their backyards and can observe when they choose to. So professionals cooperating with amateurs on a research like this is the way to go."

Related: The 9 most brilliant comets ever seen

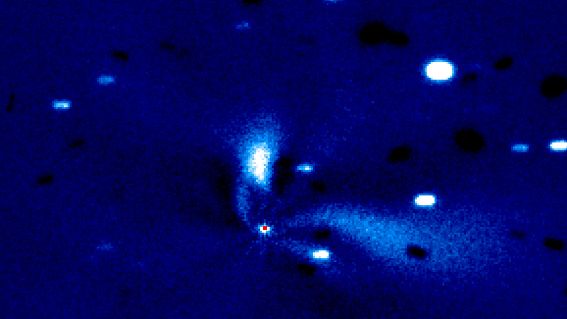

On Sept. 25, just after the full moon, the patient dedication of the devoted group of amateurs was rewarded in the most unexpected way. The comet, located in the constellation Auriga, was quite close to the moon and very faint for proper observations, but five astronomers, based in Utah, Scotland, France and on the Spanish island of Tenerife were watching.

"We spotted several sequential eruptions," said Miles. "There were four obvious ones and then a fifth one at the end. After less than two days, the brightness of the comet was something like 250 times brighter than it was before it started becoming active."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The comet's 'acting out' behavior has been notorious, but its latest performance, Miles said, was probably the most significant observed since the comet's discovery in 1927. The series of outbursts generated a bright nebulous coma, a fuzzy envelope of gas released from the surface that is typical for comets.

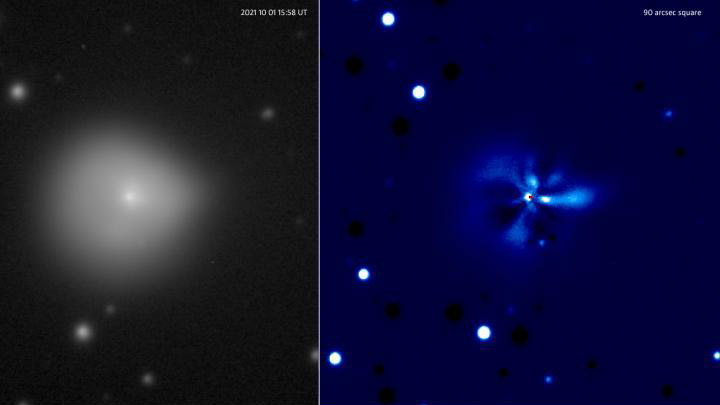

As the comet's temperamental behavior continued, Miles alerted not only other amateur astronomers, but also professionals. Since the outbursts were so unusual, a group of astronomers based at six U.S. universities managed to obtain some observation time on the Hubble Space Telescope, hoping they might be able to observe the fading coma and learn something about the comet's nature.

"This would be the first time that we would catch the aftermath of such a big outburst," John Noonan, an astronomy graduate student at the University of Arizona and one of the investigators behind the Hubble proposal, told Space.com. "The previous times that Hubble looked at Comet 29P, it's been for a smaller outburst. What's happening now is quite unprecedented, at least in the last 40 years."

Unfortunately, the veteran space telescope experienced a technical glitch on Oct. 25 and switched into safe mode, one day before it was supposed to turn its eye to the distant comet. The timing would have been perfect as the comet lit up with yet another outburst on Sunday (Oct. 24).

"We think that if Hubble can come back online at the typical timescale that it normally comes back from the safe mode events, we should still be able to get our science and to really crack the nut on this 29P case," said Noonan.

The astronomers hope that Hubble might be able to distinguish individual pieces of debris ejected during the outbursts and track these objects as they move away from the comet's nucleus.

"Hubble will be able to detect objects down to 100 meters [330 feet] in size," said Miles. "So if any fragments have been thrown into space, Hubble will be able to detect them and see them moving."

If astronomers can follow such fragments, they will be watching the birth of a completely new comet, said Noonan.

A previous study suggested that the interaction of Comet 29P with the gravity of Jupiter might fling the cosmic ice ball into the inner solar system as early as 2038, turning the Centaur into a Jupiter family comet that comes much closer to the sun. If that was the case, astronomers might be just about to make a key discovery about the processes that help comets make their way from the Kuiper Belt, the repository of space rocks beyond the orbit of Neptune, to Earth.

"If there are fragments that are being split off of it in these huge outbursts like the one that happened at the end of September, those fragments may become Jupiter family comets as well," said Noonan. "If there is a process happening in the Centaur region that could fragment incoming Kuiper Belt objects that are Centaurs for this brief period of their dynamical lifetimes, and give us these 100 to 200 meter [330 to 660 feet] size Jupiter family comets, that'd be fascinating."

The truth is that astronomers know very little about 29P and its strange behavior. Scientists don't even understand why the sudden increase of activity is occurring now. The activity of comets is usually determined by heat from the sun. The closer to the star, the more material from the icy comet vaporizes. But the orbit of Comet 29P is circular, so its distance from the sun barely changes. It should therefore not display very pronounced variations in activity, said Noonan.

Richard Miles believes that the powerful outbursts observed recently might be a result of complex geological processes taking place inside the comet as well as on its surface.

In 2014, the astronomers for the first time detected a mini-outburst on the comet. If the big outbursts, such as the recent ones, could be compared to volcanic eruptions, Miles said, the mini-outbursts are more like geysers. These mini-outbursts, the astronomers have found since, can be observed about 10 to 15 times a year, and the material these geysers shoot off falls back to the comet's surface to form a strong crust.

The presence of this crust is what then makes the powerful outbursts explode with such a force, some scientists believe.

"It's quite the same thing that happens with volcanoes on Earth," said Miles. "You have molten rock deep down and water that dissolves in it creating water vapor. Then the plug of the volcano is removed like a cork from a champagne bottle, the gas comes out of the liquid magma and you get an eruption."

But for now, these are theories. Thanks to the renewed scientific excitement for the temperamental Comet 29P, we might soon learn more.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.