Ancient surgical implant or modern-day fake? Peru skull leaves mystery.

If authenticated, the skull would represent a unique discovery in the Andes.

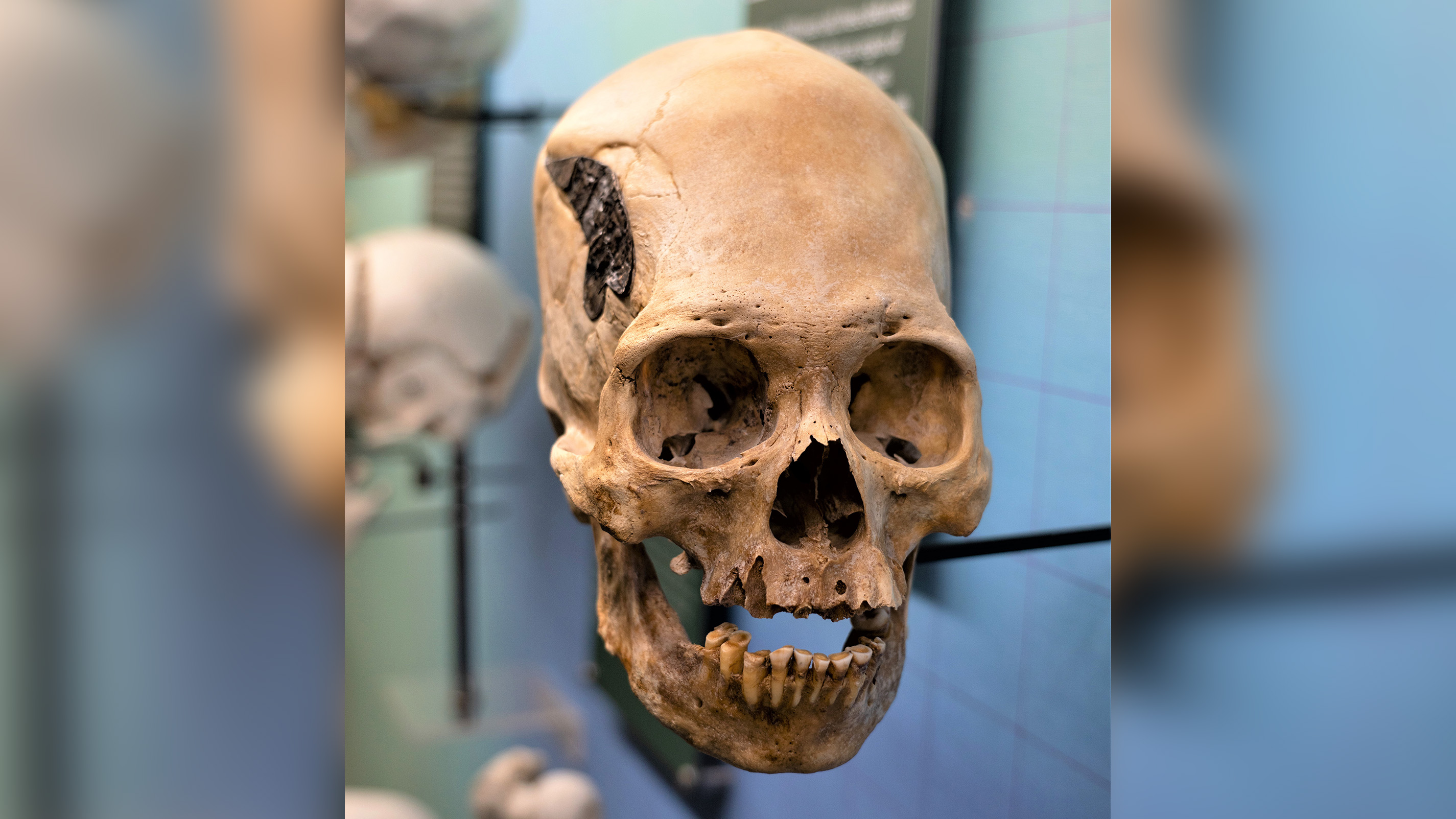

An elongated, cone-shaped skull with a possible metal implant could represent some of the earliest evidence from Peru of an ancient surgical implant. Or it could be a modern-day fake.

The fact that the skull, which was donated to the Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma City, has a cone shape is nothing too unusual, as Peruvians during ancient times were known to squeeze children's heads with bands during development to achieve the distinctive shape.

However, the metal implant in this skull is highly unusual and, if authentic, would potentially be a unique find from the ancient Andean world.

In addition to this potential implant, the skull has a hole beneath the metal that was possibly created through trepanation. Trepanation is when a hole is inserted into a person's skull in an attempt to treat an injury or medical condition, and it was a common practice in the ancient world.

Related: 25 grisly archaeological discoveries

The Museum of Osteology, which has posted several pictures of this skull on its Facebook page, said its experts are not able to verify the authenticity of the metal implant at this time. A museum representative told Live Science that no carbon dating has been done and an archaeologist has yet to examine it up close.

Is the implant authentic?

Live Science talked to several scholars not affiliated with the museum to get their take on the implant's authenticity, and overall their opinion was mixed. Some were skeptical and suggested the implant is a forgery, while others suspect the implant could be the real deal. Either way, several scientific tests will need to be done before a final determination can be made as to whether the implant is authentic, the scholars said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I'm quite dubious that this is anything authentic," John Verano, an anthropology professor at Tulane University in Louisiana, told Live Science in an email, referring to the metal implant possibly being a modern-day forgery even if the skull is legit. "In a few words, I think this is something fabricated to make the skull a more valuable collectible," Verano said. This metal implant could have been inserted many decades ago, before either the museum or the donor owned it.

Verano has examined several Andean skulls that allegedly have metal implants and published a paper on the topic in 2010 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. In the paper, Verano describes skulls that supposedly held metal implants, but they were either forgeries, or the metal was not a surgical implant at all but instead was used as a grave offering.

Other scholars told Live Science that it’s possible the metal implant could be real, but it's too early to say for certain until further tests have been carried out. "I've never seen anything like this before. Based on the pictures, it looks like the metal piece was thinly hammered into shape," Danielle Kurin, an anthropology professor at University of California, Santa Barbara, told Live Science in an email.

"Based on the fracture patterns, this individual — [who] looks to be an older male — suffered a massive blunt-force trauma to the right side of the head. The fact that the radiating and concentric fracture lines show signs of healing suggests this individual survived at least several weeks to months," Kurin added.

Since metallurgical technology varied across the Andes at the time, tests on the metal in the skull could help to shed light on where it was made, Kurin said. "It would also be helpful to have the skull X-rayed to determine if the piece of metal is covering a trepanation hole and/or an open cranial fracture."

There are a few cases from past discoveries where, after a trepanation, a piece of the person's bone or a gourd was placed in the hole that was cut out, Kurin said. Additionally, in a 2013 American Journal of Physical Anthropology article, Kurin reported on a case where a person who lived in Peru about 800 years ago wore a tight-fitting skull cap that had a metal cap stitched onto it. They wore the cap like a helmet, providing protection for the area carved out by trepanation.

Kent Johnson, an anthropology professor at SUNY Cortland, also said that the metal implant could be authentic but again said that tests need to be done. However, regardless of whether or not the implant is real, the person it was placed on did survive an awful injury.

"It is fair to describe this individual as a survivor. There is extensive trauma to the right side of the cranium affecting the frontal, temporal and right parietal bones," Johnson told Live Science in an email, noting that the person seems to have survived for a time after these injuries. "There is evidence of healing where the edges of the fractured bones had sufficient time to grow back together."

It's not clear at the moment when tests on the skull will take place.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.