Editor's Note: This story was updated at 1:15 p.m. E.D.T. on May 1

As the new coronavirus burns its way across the world, scientists are rushing to find ways to identify those who have been infected — including those who have recovered from COVID-19. Those people, the thinking goes, may be immune to the deadly virus and could theoretically help restart the economy without fear of reinfection.

One key piece of this puzzle is rolling out what are known as serological tests that look for specific antibodies in a person's blood. So far, they have been used to estimate how much of the population has been exposed in different areas, such as New York City and Los Angeles.

But what are these tests, and can they really help to identify who is immune to SARS-CoV-2? From how they work to what they tell us, here's everything you need to know about coronavirus antibody testing.

Related: Live updates on COVID-19

What are antibody tests?

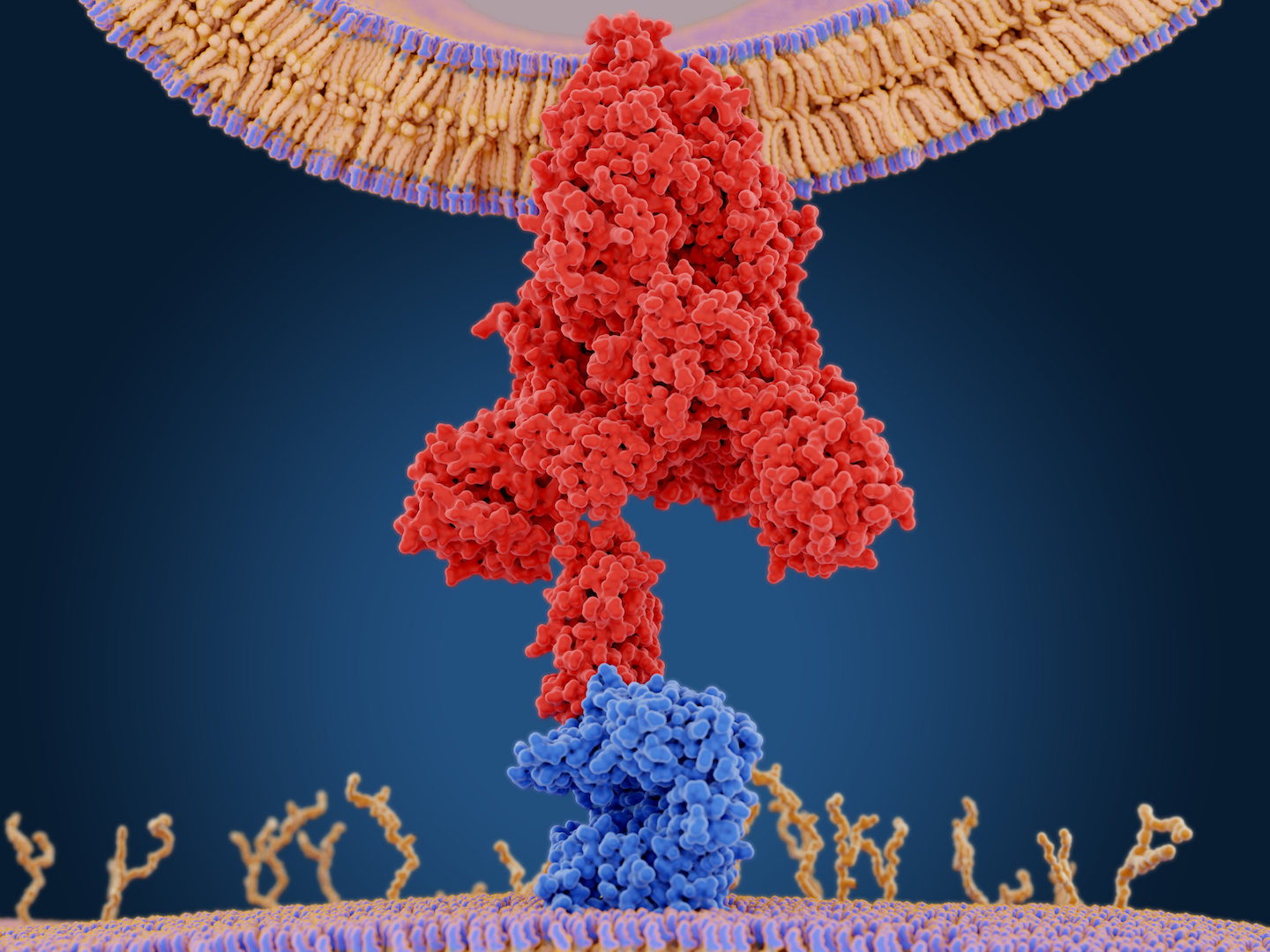

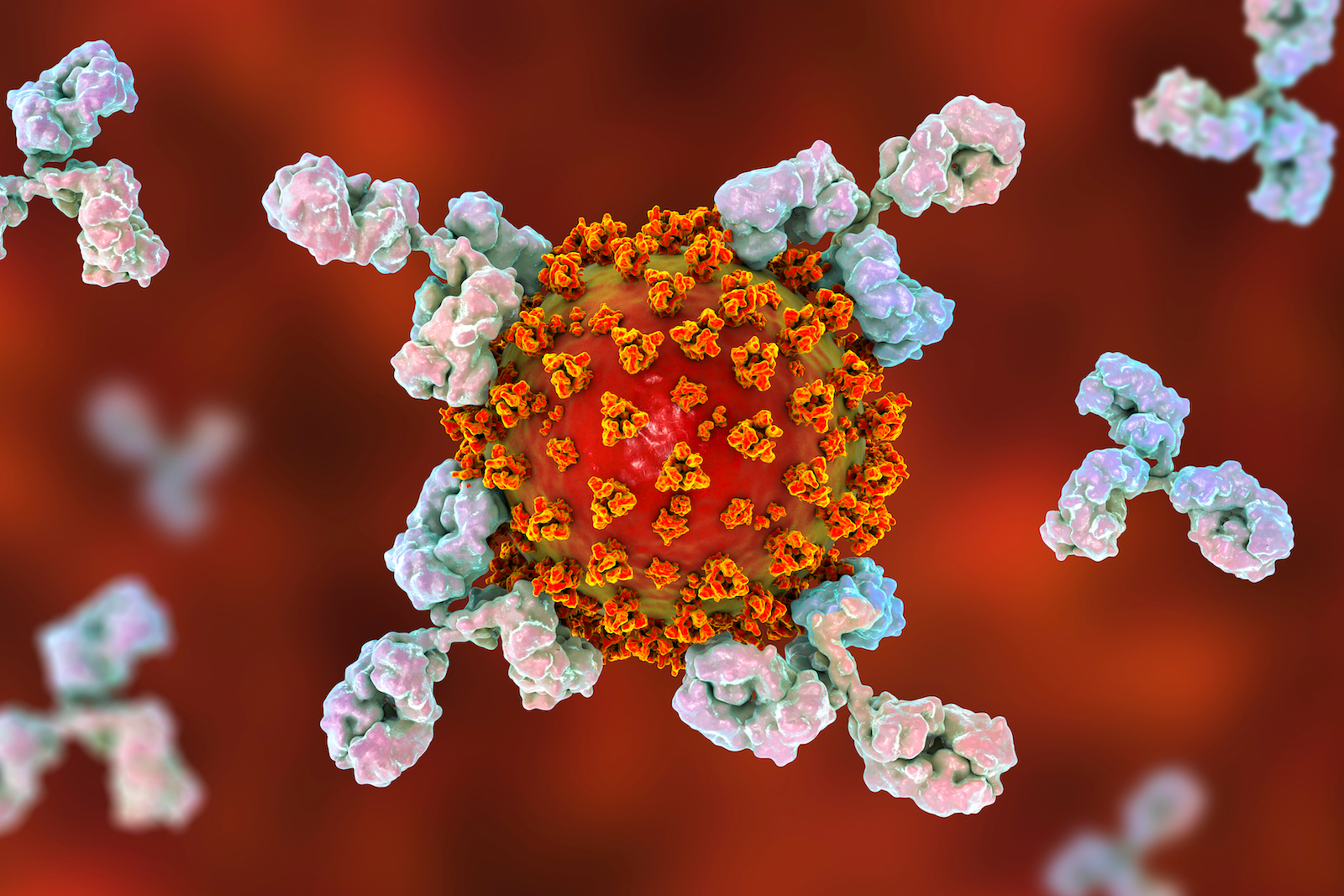

Within hours of a foreign invader, such a SARS-CoV-2, infiltrating the body, the immune system mounts a nonspecific attack, meaning the body’s “general fighters” get thrown at the invader. But eventually the body begins to send out large, Y-shaped molecules called antibodies that target the virus precisely. Antibodies bind like a lock-and-key to a specific part of the virus.

Antibody tests are designed to detect these molecules.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The purpose of an antibody test is, instead of asking you whether or not you felt sick with COVID-19, we could instead ask your immune system if your immune system has seen the coronavirus," said Daniel Larremore, an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science and the BioFrontiers Institute at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Related: 13 coronavirus myths busted by science

Antibody tests are usually designed to detect one of two types of molecules, immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G. Within a few days to a week after a pathogen infects the body, the immune system produces a small amount of immunoglobulin M; then, several days to two weeks later, the body sends out large quantities of immunoglobulin G, Live Science previously reported. Because this immune response takes a while to show up, antibody tests will be negative for those newly infected with COVID-19, which is why they're not used for diagnosis.

"If it's the beginning of the infection, you don't pick it up, it's something that only develops later," Dr. Melanie Ott, a virologist and immunologist at the Gladstone Institutes and a professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

How do antibody tests work?

There are two types of antibody tests generally being used to test for SARS-CoV-2 — lateral flow immuno-assays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Both use the same basic principle: A sample of a person’s blood or serum (liquid part of blood) gets washed over a surface holding the molecules that antibodies bind to. When antibodies bind to those target molecules, the test reads out with another chemical reaction, such as a color change.

"The lateral flow immuno-assays are very easy to run quickly and by anyone — they essentially are similar to a pee-on-a-stick pregnancy test (but using blood or sera rather than pee) in that they give you a visual readout very rapidly," Jesse Bloom, a virologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, told Live Science in an email.

Related: 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

Lateral flow assays are very easy to use and read out very quickly, but they are not customizable, Larremore told Live Science. On the other hand, ELISA tests have to be run in a lab — they may use pipetting and plates and require technicians to run; and results take longer to get, usually about 2 to 3 hours, Charlotte Sværke Jørgensen, who studies Virus and Microbiological Special Diagnosis Serology at the Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen, told Live Science in an email.

Each antibody test picks a specific part of the virus as their target molecule. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, most of the tests are focusing on the virus’ spike protein that it uses to invade cells. Some tests are binding the S1 region of the coronavirus spike protein (the spike protein has two subunits, S1 and S2), Jørgensen said. Others are binding a small part of S1, called the receptor-binding domain (RBD), which is the specific protein that latches onto the human ACE2 receptor to enter cells. The RBD may be the most specific part of the antibody for SARS-CoV-2, since other parts of the virus look more like other coronaviruses, Jørgensen said.

What makes an antibody test good?

In general, you want a test that is both very sensitive and very specific. Sensitive means that the test catches as many people who were truly infected with the virus as possible. Specific means you don't have many "false positives," or people who test positive even if they've never been exposed to SARS-CoV-2, both Bloom and Larremore said.

That false positive rate is especially important now. Most people in the U.S. have not been exposed to SARS-CoV-2, which means that false positives can dramatically skew the results. If a test is 98% specific, for example, that means that if 100 people test positive for the virus, 98 of those people were truly infected, and two of those people actually never had it. That sounds good on paper, but if only 1% of the population is infected, then you may find one person who was truly positive, and another two people who test positive incorrectly. Most of the people who test positive have never been infected, Bloom told Live Science. The rarer the virus in the population, the more important the specificity is. (Recent antibody testing results in Santa Clara County and Los Angeles County have been criticized for having this problem.)

To ensure tests have good specificity and sensitivity, manufacturers should "calibrate" tests. That involves using blood or serum samples from people who have been confirmed to have had COVID-19, and making sure the antibody test reads positive for a high proportion of those people. On the flip side, to make sure the test isn't creating a lot of false positives, you want to test the blood of people who are known to have never had COVID-19. Because no one in the world was likely exposed to the new coronavirus before fall of last year, you ideally want samples from before that period — but not ones that are too old.

Just like produce at the grocery store, "we want blood samples that are fresh and local," Larremore said.

That way, the blood samples will have antibodies to other coronaviruses (such as ones that cause common colds) that were circulating in the region during the season, Larremore said.

"We need to make sure that our test doesn't go off when it sees those coronaviruses," Larremore said.

ELISA tests can be calibrated and fine-tuned for a local community using local samples. (Different coronaviruses could have been circulating in different regions, so testing with local samples can make sure your test doesn’t falsely ping for the coronaviruses that were most common in that region.) But more "out of the box" lateral flow assays can't be customized, and if the control samples they used were from, say China, then they may be fine for detecting the true cases of COVID-19, but not for eliminating false positives. A miscalibrated test could overstate the results of any kind of community survey that estimates the virus's prevalence, he added.

And as you'd expect, the more samples are used to calibrate the tests, the better the results. (Larremore has built an online calculator that can use the calibration data of a specific test to predict is sensitivity and specificity.)

Does having antibodies mean I'm immune?

Another tricky part of antibody testing is that we don't know what it means for long-lasting or even short-term immunity. Some people who have beaten COVID-19 may not generate antibodies at all, but that may not mean they're not immune. For instance, a study published April 6 to the preprint database medRxiv, which has not been peer-reviewed, found that of 175 COVID-19 patients in China, about 30% (who tended to be younger) had very low levels of antibodies — yet those people also recovered just fine. And it's also possible that the body makes different antibodies than a test will pick up, meaning you could be immune but still test negative.

Related: Treatments for COVID-19: Drugs being tested against the coronavirus

On the flip side, some people may develop antibodies, but those antibodies may not be very effective at neutralizing the virus, Ott said.

Other coronaviruses paint a mixed picture on immunity. People generated antibodies to the more severe coronaviruses, SARS and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome), for at least a few years, according to a 2017 study in the journal Viral Research. But strains of coronaviruses that cause the common cold can reinfect the same person within a year, according to a study still undergoing peer review but published online by Columbia University. It's still too early to say which camp SARS-CoV-2 falls into.

"Bottom line, if you make antibodies, you probably have some type of immunity. But we don't know what and how long," Ott told Live Science.

That means reliable antibody tests can estimate how many people have been infected, but they can't tell an individual that they're immune to the disease.

Right now, tons of antibody tests have flooded the market. But the results can be tricky to interpret because we don't know how reliable they are, Ott said.

"Science needs time to do things properly," Ott said. "That virus is not leaving us much time. But sometimes it doesn't help to rush something."

Editor's Note: This story was corrected to update Melanie Ott's affiliation. The Gladstone Institutes is not part of UCSF, though Ott is a professor at the latter.

- The 9 deadliest viruses on Earth

- 28 devastating infectious diseases

- 11 surprising facts about the respiratory system

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.