Sharing a single ventilator between 4 patients is possible. But it could be disastrous.

Usually a ventilator supports just one person. Can it support more?

Editor's note: This story was updated on at 2:55 pm E.D.T to include a joint statement from a number of societies, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists. It was updated at 5:15 pm E.D.T to note that a hospital in New York City is practicing ventilator sharing.

There aren't enough ventilators in the United States to keep alive the hundreds of thousands of people who will need them during the COVID-19 pandemic. There may be a stopgap, however.

Doctors can reconfigure existing ventilators so that these lifesaving devices serve either two or four patients simultaneously, rather than just one at a time, according to a 2006 feasibility study in the journal Academic Emergency Medicine.

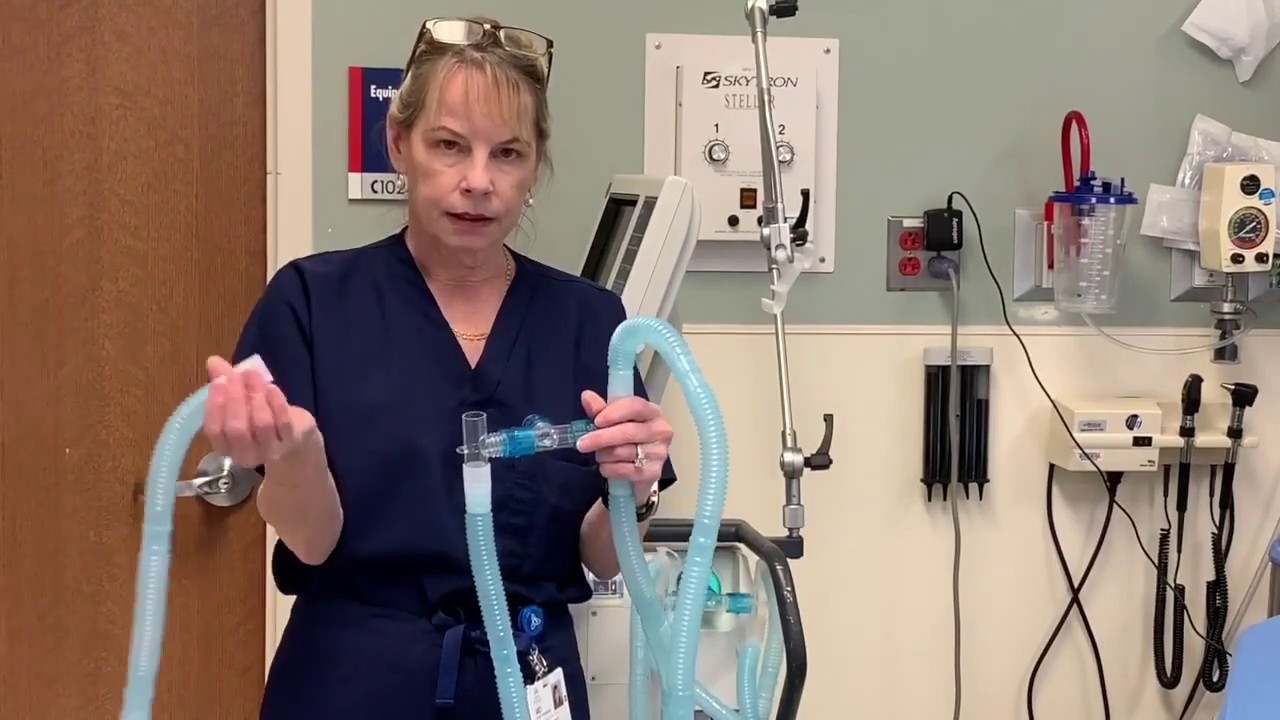

The study was written in the aftermath of 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, but in light of the new coronavirus outbreak, one of the study's authors published a YouTube tutorial to show how this idea could work for patients whose breathing is impaired by the new coronavirus.

"In that study, we just looked at simple equipment available in the emergency department and a way to modify the ventilator to ventilate four patients," study co-author Dr. Charlene Irvin Babcock, an emergency medicine physician at St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit, said in the video.

Related: Coronavirus in the US: Latest COVID-19 news and case counts

A ventilator is a machine that can help a person breathe by delivering oxygen through a tube placed in the mouth or nose, or through a hole in the front of the neck, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In essence, the study shows that a ventilator can be modified with adapters and T-shaped tubes so that it has four ports for four patients, said Babcock, who co-wrote the study with Dr. Greg Neyman. At the time, Neyman was a resident in emergency medicine at St. John Hospital and Medical Center, and now works as an emergency physician at several hospitals in Hamilton, New Jersey.

Their experiment simulated four adults weighing 154 lbs. (70 kilograms) getting ventilation for 12 hours. However, Babcock cautioned that transforming a ventilator this way is "off label," meaning that it's not approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Moreover, it was never studied in people; the 2006 study merely used lung simulators, rather than human subjects.

But this idea was put to use by Dr. Kevin Menes, an emergency room physician who treated mass shooting victims at the 2017 Las Vegas country music concert. Menes had been a resident with Neyman, so he was aware of the ventilator study. (You can read about Menes' harrowing night at Sunrise Hospital in Las Vegas here.)

"You can imagine that with a lot of penetrating torso and CNS [central nervous system] injuries, [Menes] intubated a lot of patients," Babcock said. "They received a large volume of patients very quickly and they ran out of ventilators."

So, Menses directed that each ventilator get reconfigured with one T-tube so it could serve two patients. "It was very successful," Babcock said. "He was able to keep them alive for hours as they waited for outside ventilator supports to come in and help them supply the patient need."

This past week, with the COVID-19 crisis, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital in Manhattan began practicing ventilator sharing, according to The New York Times. For now, the hospital is putting a maximum of two people on a single ventilator. But some people are still getting their own if they have a complex case, Dr. Jeremy Beitler, a pulmonary disease specialist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia, told The New York Times.

However, in a statement released today (March 26), medical societies across the country came out strongly against this idea. "Sharing mechanical ventilators should not be attempted because it cannot be done safely with current equipment," the societies said in the statement. "The physiology of patients with COVID‐19‐onset acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is complex." Even in ideal circumstances, 40% to 60% of ventilated patients with ARDS and lung disease die, they said.

"It is better to purpose the ventilator to the patient most likely to benefit than fail to prevent, or even cause, the demise of multiple patients," they said. The statement is supported by the following: the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (ASPF), American Association of Critical‐Care Nurses (AACN) and American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Even Babcock said that using a ventilator for multiple people isn't going to be easy. Doctors would have to pair together patients with similar lung sizes. "You wouldn't want to put a pediatric patient with an adult patient, because that wouldn't make sense," Babcock said. "It wouldn't be able to ensure that the same volume [of oxygen] is delivered everywhere appropriately."

Furthermore, patients need to be breathing with the same resistance to the ventilator's oxygen flow. "You wouldn't want to put a patient with severe bronchospasm with a patient who did not have bronchospasm," a condition in which the muscles tighten in the lungs, which can make breathing difficult, Babcock said. That's because people breathing with different resistances "might change the amount of volumes, and it wouldn't make sure that there were equal volumes delivered to everybody," she said.

Related: Tiny & nasty: Images of things that make us sick

Using the same ventilator for multiple people could spread germs, but in this case, these patients would have COVID-19 already anyway, Babcock noted. In addition, the patients would need to be sedated for this to work, Babcock added in the YouTube comments.

But this setup is designed to be a temporary one, used only when there is a "disaster surge involving multiple casualties with respiratory failure," the researchers wrote in the study. COVID-19 patients typically need artificial ventilation for longer than 12 hours, the amount of time analyzed in the study. And if one patient improves and needs less oxygen, while another worsens and needs more, a ventilator hooked up to two people could not adjust to both of them, as ProPublica reported. Getting too little or too much oxygen can damage the lungs.

"I have never heard of ventilators being shared between multiple patients as the process of ventilation is very personal — the controls and sensors are set to satisfy an individual patient['s] needs and wellbeing," Mark Tooley, a fellow at the Royal Academy of Engineering in the United Kingdom, told MailOnline in response to the video and study. "'The risk of infection would also be high if used for seriously ill patients. In theory it could be possible, but it would be a very complex procedure, fraught with issues."

In the meantime, states are frantically trying to acquire ventilators. For instance, Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced that New York has procured about 7,000 ventilators, but needs at least 30,000 more, according to ABC News. Some companies are also switching gears to make them, including SpaceX and Tesla, run by Elon Musk, Live Science previously reported.

- The 9 deadliest viruses on Earth

- 28 devastating infectious diseases

- 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.