The new coronavirus: Your questions answered

A new coronavirus is spreading around the world, having caused nearly 100,000 illnesses and thousands of deaths globally. Here are answers to some basic questions about the new coronavirus.

What is the new coronavirus?

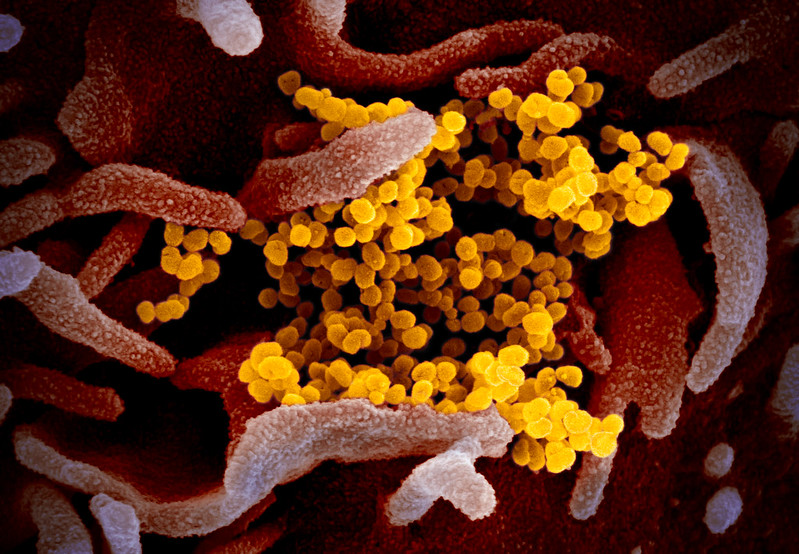

Coronaviruses constitute a large family of viruses that can cause respiratory illnesses such as the common cold. The new virus is a type of coronavirus that had never been seen before. It first appeared in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Officials have named the new virus SARS-CoV-2, due to its genetic similarity to the coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS. The official name for the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is COVID-19.

What are the symptoms?

Reported symptoms in patients have varied from mild to severe and can include fever, cough and shortness of breath, according to the CDC. Read more about coronavirus symptoms.

How long does it take for symptoms to show up?

The time between catching a virus and showing symptoms of the disease is known as the incubation period. For the new coronavirus, the inucbation period is estimated to be between one day and 14 days, although some studies have reported an incubation period as long as 24 days. Read more about the incubation period for the new coronavirus.

How does the coronavirus spread?

The virus is thought to spread mainly through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes. But other transmission routes are possible. Read more about the spread of the new coronavirus.

How deadly is the virus?

The fatality rate of the new coronavirus is still being studied, but it appears to be deadlier than the flu, which has a fatality rate of about 0.1%. In a large study published Feb. 18 in the China CDC Weekly, researchers found a death rate from COVID-19 to be around 2.3% in mainland China. But on March 5, the World Health Organization announced a slightly higher fatality rate of around 3.4%. Still, it's possible that mild cases of the virus are being missed, which could lower the death rate. Overall, older adults and those with underlying medical conditions appear to most at risk for serious complications from COVID-19. Read more about the death rate of the new coronavirus.

Where did the coronavirus come from?

The exact source of the new coronavirus is not known. In a new study, however, the researchers compared the genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2 (formerly called 2019-nCoV) with those in a library of viral sequences, finding that the most closely related viruses were two coronaviruses that originated in bats; both of those coronaviruses shared 88% of their genetic sequence with SARS-CoV-2. Another study found 96% similarity between a virus found in bats and SARS-CoV-2.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Based on these results, the study authors said that SARS-CoV-2 likely originated in bats. However, no bats were sold at the Huanan Seafood Market, the market in Wuhan where the outbreak is thought to have originated, which suggests that another, yet-to-be-identified animal acted as a steppingstone in transmitting the virus to humans.

A handful of studies have suggested that this "intermediate" animal was the pangolin, an endangered, ant-eating mammal. However, viruses found in samples from illegally trafficked pangolins were not similar enough to SARS-CoV to prove that the scaly anteaters were the source for the new virus, Nature reported.

A previous study suggested snakes, which were sold at the Huanan Seafood Market, as a possible source of the new virus. However, some experts have criticized that study's analysis, saying it's unclear if coronaviruses can infect snakes.

What is the treatment?

There is no specific treatment for COVID-19. For patients who have gotten this disease, treatment has involved "supportive care," such as fluids and medication to relieve symptoms like shortness of breath. For severe cases, treatment should include care to support vital organ functions, the CDC said. Read more about treatments for COVID-19.

On Feb. 25, U.S. officials announced that a clinical trial to evaluate a treatment for COVID-19 was underway, according to the National Institutes of Health. The trial will test an antiviral drug called remdesivir in hospitalized adults who have COVID-19. The first study participant is an American who caught the disease while onboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship. That person is being treated at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. The study can be adapted to examine other treatments and enroll patients at other sites in the U.S. and worldwide, officials said.

How can you protect yourself?

There is not currently a vaccine to prevent COVID-19. However, research on a vaccine is in the works, and a trial testing an experimental vaccine is set to begin soon. Read more about the COVID-19 vaccine trial.

The best way to prevent infection with COVID-19 is to avoid being exposed to the virus, the CDC said. In general, the CDC recommends the following to prevent the spread of respiratory viruses: Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds; avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth with unwashed hands; avoid close contact with people who are sick; stay home when you are sick; and clean and disinfect frequently touched objects and surfaces.

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.