Cosmic 'tadpole' points to ultra-rare black hole hiding near the Milky Way's center

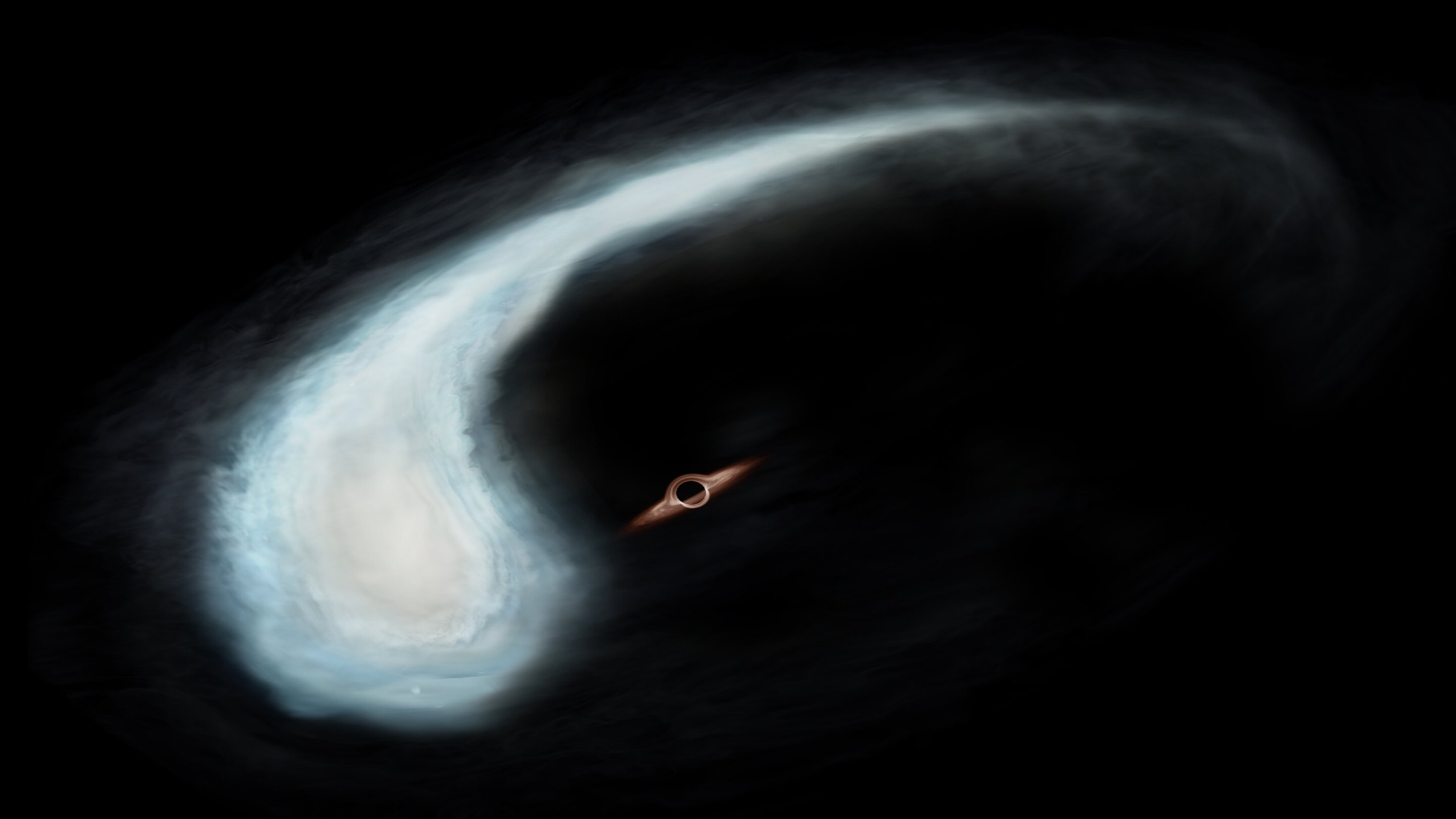

Scientists detected a cloud of gas sculpted into a wonky tadpole shape near the Milky Way's center, possibly pointing to a rare intermediate-mass black hole.

An enormous, deformed dust cloud that astronomers nicknamed "the Tadpole" could point to the location of an extremely rare type of black hole never confirmed to exist in our galaxy before.

In a study published Jan. 10 in The Astrophysical Journal, researchers based in Japan describe the strange dust cloud, which looks like a big-headed, long-tailed tadpole and sits near the center of the Milky Way in the constellation Sagittarius, about 27,000 light-years from Earth.

This region of the Milky Way, known as the Central Molecular Zone, is extremely dense with star-forming dust clouds that clump around our galaxy's central supermassive black hole, known as Sagittarius A*. Even in this extreme environment, the Tadpole's shape and movement stood out to the researchers.

Using observations from the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii, as well as the Nobeyama 45-m Radio Telescope in Nagano, Japan, the team analyzed the Tadpole and its surrounding environment in multiple wavelengths. The researchers determined that the Tadpole was being stretched into its unusual shape by the intense gravitational pull of a nearby object. However, no matter which wavelengths they looked in, the team's search revealed no signs of anything massive enough to cause such a deformation.

This glaring absence revealed a big clue about the invisible object's identity.

"The spatial compactness of the Tadpole and absence of bright counterparts in other wavelengths indicate that the object could be an intermediate-mass black hole," the researchers wrote in the study.

Related: What happens at the center of a black hole?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Black holes are so massive that nothing, not even light, can escape the pull of their gravity, so astronomers can't see them directly. However, researchers can identify black holes based on the way these cosmic monsters warp the space and objects around them.

Most black holes discovered to date fall into two categories: stellar-mass black holes, which can weigh up to 100 times the mass of Earth's sun and form when massive stars collapse under their own weight; and supermassive black holes, which sit at the centers of almost all large galaxies and can be millions to billions of times more massive than the sun. Scientists still aren't certain how the universe's supermassive black holes formed.

Between those two categories is an elusive third type of black hole: intermediate-mass black holes. These objects, which could measure between 100 and 100,000 solar masses, are considered a "missing link" in black hole theory, as their medium size could represent a crucial growth stage between smaller black holes and supermassive ones.

So far, only a handful of intermediate-mass black hole candidates have been identified across the universe. None have ever been proven to exist in the Milky Way, though several candidates have been spotted, including four others near the galactic center.

When the study authors calculated the mass required to stretch the Tadpole into its distinct shape, they found that a black hole measuring roughly 100,000 solar masses was the likeliest culprit.

Although the finding requires further observations to confirm, the existence of yet another potential intermediate-mass black hole near the galaxy's center suggests that they may be more plentiful there than astronomers previously thought. This gives future researchers a promising target to study in their hunt for one of the universe's most massive missing links.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.