How a superspreader at choir practice sickened 52 people with COVID-19

A COVID-19 superspreader unknowingly infected 52 people with the new coronavirus at a choir practice in Mount Vernon, Washington, in early March, leading to the deaths of two people, a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report finds.

The choir practice happened on March 10, roughly two weeks before the state's Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee issued the March 23 "stay home, stay healthy" executive order, which barred social gatherings and nonessential travel as a way to stem COVID-19 infections.

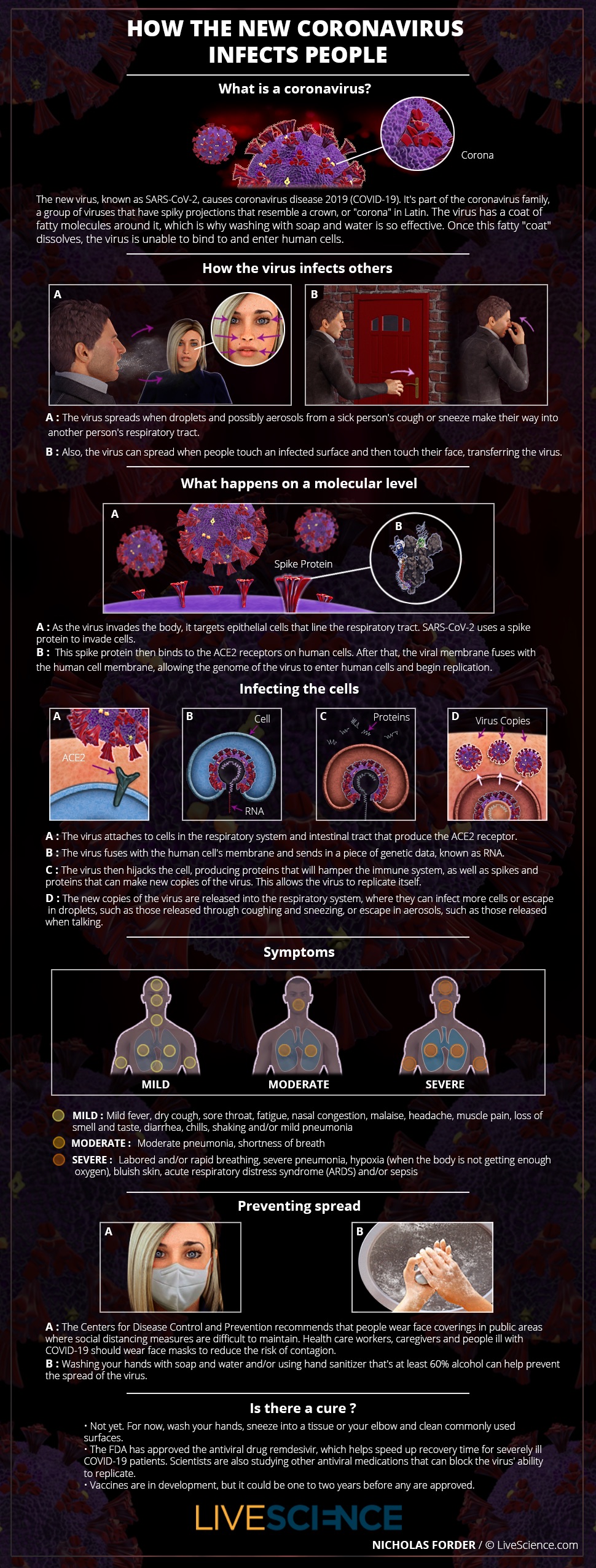

While the choir members took a few precautions at the practice, such as not hugging or shaking hands, these measures fell short of protecting them from the virus. If anything, this event shows "the importance of physical distancing, including maintaining at least 6 feet [about 1.8 meters] between persons, avoiding group gatherings and crowded places, and wearing cloth face coverings in public settings where other social-distancing measures are difficult to maintain during this pandemic," according to the report, published online May 12 in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Related: 13 Coronavirus myths busted by science

In early March, COVID-19 infections were rising in the greater Seattle area, about an hour's drive south of Mount Vernon. But while Seattle's King County had 270 confirmed cases on March 10, Mount Vernon's Skagit County had just two, according to the Washington State Department of Health.

So, 61 members of the Skagit Valley Chorale, half of the choir's singers, came to the evening practice at the Mount Vernon Presbyterian Church, according to the Los Angeles Times, which broke the story.

One of those singers had COVID-19. This person had cold-like symptoms starting on March 7, but didn't realize it was the new coronavirus until a test later confirmed the diagnosis, according to the CDC report, which was written by Skagit County Public Health (SCPH) professionals. People infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, are most infectious from 2 days before through 7 days after symptoms begin, SCPH said in the report, "which could have placed the patient within this infectious period during the March 10 practice."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The practice lasted 2.5 hours. Several members arrived early to place the chairs — arranged in six rows of 20 and spaced 6-10 inches (15-25 centimeters) apart. Once seated, the singers practiced together for 40 minutes, split into smaller groups for a 50-minute practice block, took a 15-minute break that included shared snacks of cookies and oranges, and reconvened for a final 45-minute singing session.

Within days (an average of three), people began showing symptoms of COVID-19. Most of the choir's members are older women, and women comprised 85% of the choir cases. The median age of those infected was 69 years old. Excluding the superspreader, 52 of the 60 singers (or 86.7%) became ill. However, only 32 had a test to confirm the illness; the other 20 likely had it, based on their symptoms, said SCPH, which interviewed all of the members present.

Most of the patients (67.9%) did not have any underlying conditions. However, the three singers who were hospitalized had two or more underlying medical conditions. Two of those patients later died.

How did it spread?

There are a number of ways the virus could have spread from the superspreader. However, "transmission was likely facilitated by close proximity (within 6 feet) during practice and augmented by the act of singing," according to the report.

Related: 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

Previous research has suggested that COVID-19 may spread through breathing and talking. A study released yesterday (May 13) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) found that 1 minute of loud speaking can generate more than 1,000 virus-containing droplets, and those droplets can remain airborne for 8 minutes or longer.

Those new results suggest that talking with an infected person in a confined space can carry a substantial risk of virus transmission, the authors wrote in the PNAS study.

It's also possible that the virus may have spread if the singers put their hands on commonly touched surfaces, such as the chairs, and then touched their faces, the report said.

Superspreader events can have a dramatic impact on the course of an outbreak. For instance, a superspreader in South Korea infected 40 people with COVID-19, and a U.K. man who likely contracted the virus during a business trip in Singapore passed it onto 11 people at a ski resort in France, Live Science previously reported. In a separate case, a 29-year-old man infected 101 people after visiting several nightclubs in Seoul, South Korea, CNN reported. A Biogen conference in Massachusetts led to 99 people from the state being infected, and may have seeded outbreaks in several other states, the Boston Globe reported. Ultimately, most of the cases in Massachusetts were seeded by that event, according to the Globe.

"The potential for superspreader events underscores the importance of physical distancing, including avoiding gathering in large groups, to control spread of COVID-19," the CDC report said. "Enhancing community awareness can encourage symptomatic persons and contacts of ill persons to isolate or self-quarantine to prevent ongoing transmission."

- When will a COVID-19 vaccine be ready?

- 11 surprising facts about the respiratory system

- 11 (sometimes) deadly diseases that hopped across species

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.