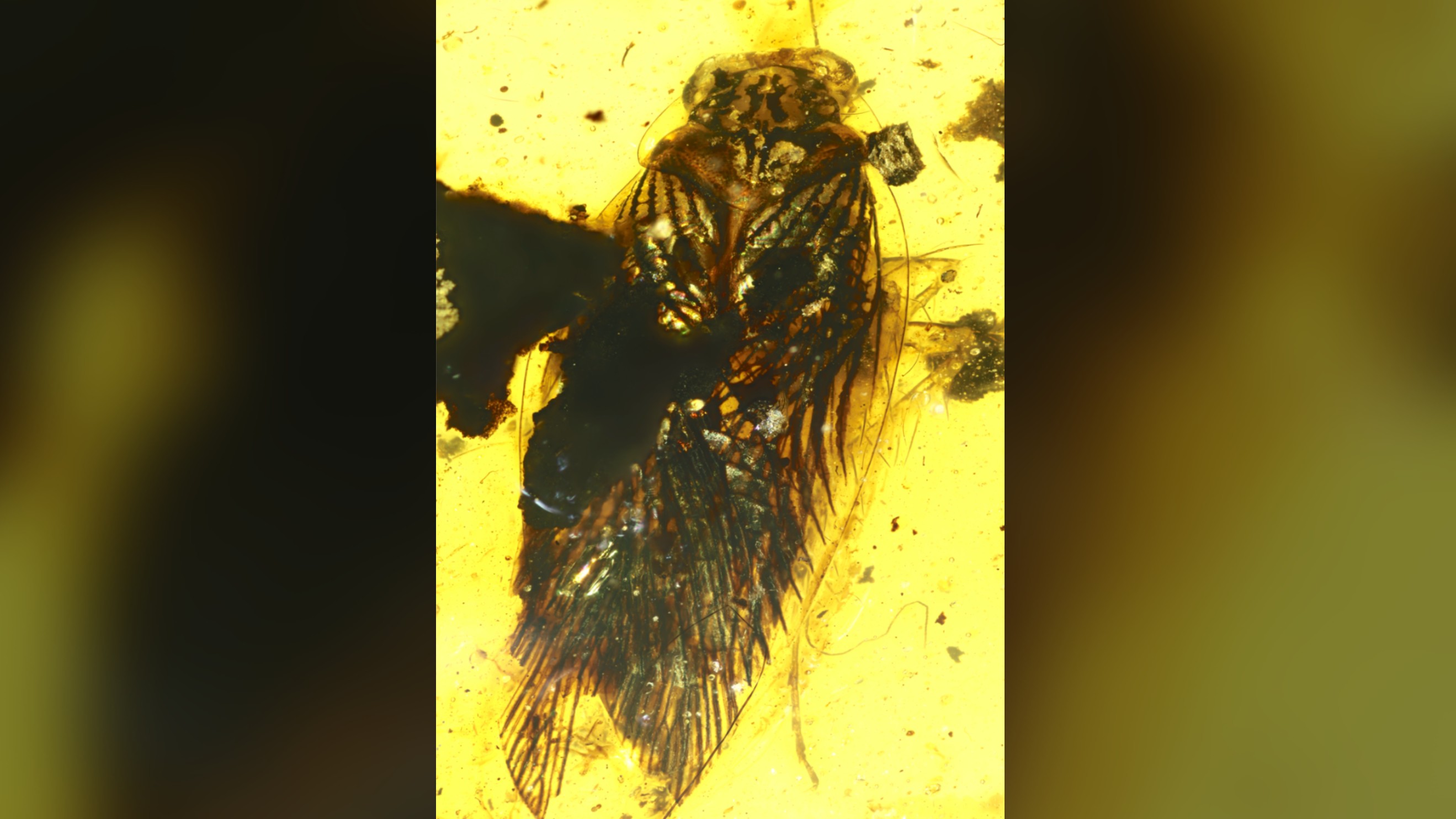

Creepy, big-eyed cockroach discovered trapped in amber from 100 million years ago

This ancient cockroach relative had huge peepers.

Today's cockroaches are nocturnal creepy crawlers that scatter when you turn on the light. But their ancient relatives were likely the polar opposite, according to the discovery of an immaculately preserved, big-eyed cockroach trapped in amber.

Its huge peepers likely helped it forage during the day, when the sun was blazing overhead.

Researchers already knew about the existence of this unique, now-extinct cockroach, scientifically known as Huablattula hui, but this is the first time that they've gotten such a detailed look at its eyes.

"The cockroach specimen was remarkably well preserved and showed many morphological features in fine detail," study lead researcher Ryo Taniguchi, a graduate student in the Department of Natural History Sciences at Hokkaido University in Japan, said in a statement.

Related: Ancient feathered friends: Images of feathers in amber

Animals use sensory organs to navigate their surroundings in order to to find food, avoid predators and locate mates. Because sensory organs are often adapted to specific lifestyles, scientists can often learn a lot about an animal's quirks by examining each organ that gathers sensory information. For example, owls have asymmetrical hearing, which allows them to triangulate the location of both predators and prey, while cave-dwelling fish often forgo eyes, which are useless in dark underground pools.

However, when it comes to extinct species — especially insects, whose delicate eyes, antennae, ears and tongues don't fossilize well in sediments — studying sensory organs can pose unique challenges. "Insect organs are rarely preserved in sediments because they are so small and fragile," Taniguchi said. "One way to solve this problem is to study exceptionally well-preserved fossil material from amber."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Amber is ideal because it is able to directly preserve the tissues of a small insects trapped within, while fossils preserved in sediments typically don’t preserve the tissues directly.

That's just what happened to this male H. hui cockroach. About 100 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period, it got stuck and died in a glob of tree resin, which later fossilized into amber, in what is now Myanmar.

Taniguchi and his colleagues from Hokkaido and Fukuoka universities used a variety of techniques, such as photography and micro-CT, to examine the specimen's uniquely intact sensory organs. They examined the eyes by using microscopy and photography, but the minuscule structures of the antennae required an even higher-resolution approach; a technique called thin-sectioning, which involved making slices of the amber that were only 200 micrometers wide, just wider than a human hair.

These techniques revealed a cockroach with a sensory world mostly unknown to the roaches in modern basements. Typically, modern cockroaches have underdeveloped eyes, but feel around through highly sensitive touch sensors on their antennae. In contrast, this ancient species had well-developed compound eyes, while at the same time having a fraction of the antennae touch sensors that its modern relatives have.

"These lines of morphological evidence in sensory organs indicate that this species relied on the visual system in their behavior, such as searching for food and finding predators," Taniguchi told Live Science in an email.

Based on these sensory structures, it's likely that this ancient critter behaved more like modern-day mantises, a close roach relative that is active during the daytime, Taniguchi said.

The finding suggests that roaches may have been much more ecologically diverse in the past than they are today. The vast majority of the 4,600 living cockroach species are adapted to spending most of their lives in darkness. However, modern-day nocturnal cockroaches are not descended from H. hui. Instead, this Cretaceous roach is representative of a lineage that may have been driven to extinction through competition with other insects, which likely relegated roaches to dark corners and caves.

Taniguchi hopes that this type of "paleo-neurobiology," or the study of neurological features, such as the tiny sensory organs of insects, will continue to develop into the future, providing scientists with even more clues about the sensory worlds of long-gone insects.

This study was published in September 2021 in the journal The Science of Nature.

Originally published on Live Science.

Cameron Duke is a contributing writer for Live Science who mainly covers life sciences. He also writes for New Scientist as well as MinuteEarth and Discovery's Curiosity Daily Podcast. He holds a master's degree in animal behavior from Western Carolina University and is an adjunct instructor at the University of Northern Colorado, teaching biology.