Here's every spaceship that's ever carried an astronaut into orbit

SpaceX's Crew Dragon could become #9.

The hundreds of people who have been to space have traveled on just a handful of vehicles, eight in all over nearly six decades of spaceflight.

Soon, a ninth will take flight, as SpaceX's Crew Dragon is scheduled to blast off from Florida on May 30 (after a delay due to bad weather) carrying two NASA astronauts in a test mission to the International Space Station. Four crewed vehicles to date have been American spacecraft, a point NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine emphasized in remarks made during a May 1 news conference about the upcoming SpaceX launch, called Demo-2.

"We think about Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and then space shuttle: Those are really the four times in history where we have put humans on brand-new spacecraft, and now we're doing it for a fifth time," Bridenstine said. "It's been a long time since we put humans on a brand-new spacecraft, but that's what this is."

Let's take a spin through the company Crew Dragon will join.

Related: The history of rockets

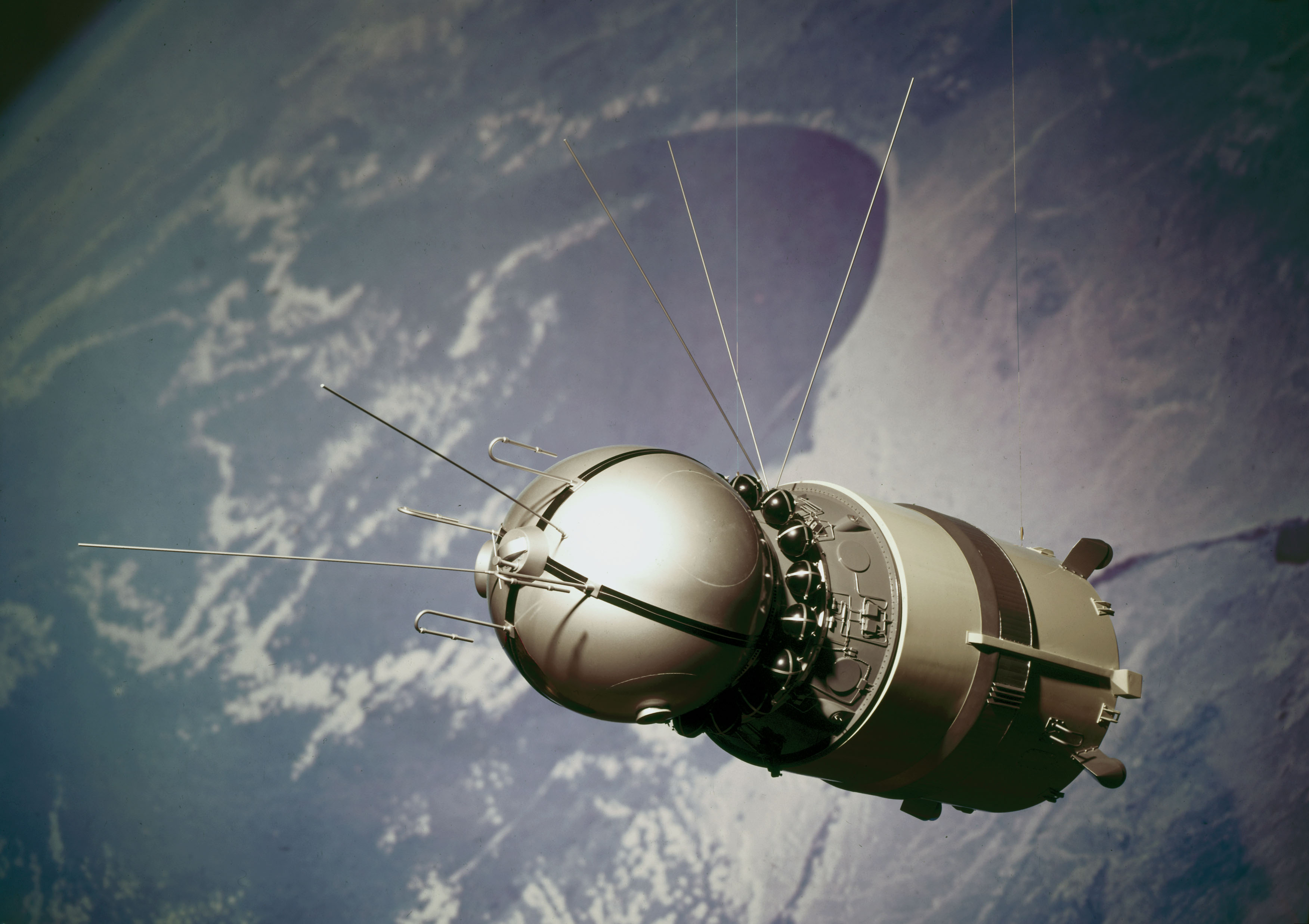

Vostok (USSR, 1961)

The Vostok capsule carried the first-ever human to make a spaceflight, the Soviet Union's cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, who launched on April 12, 1961 and clocked in with just over one full orbit of Earth.

Vostok could carry just one astronaut in its main spherical cabin, which perched atop a belt of life-support gas tanks and a pyramidical instrument module that was jettisoned before the cabin reentered Earth's atmosphere. A window near the astronaut's feet allowed them to observe Earth during flight.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The capsule had no landing gear; instead, Gagarin and his successors ejected from the capsule during the reentry process, although the Soviet Union hid that fact lest the mission not be considered a true spaceflight.

Vostok translates as "East;" Gagarin's capsule went by the call sign Swallow, according to NASA. Six Vostok capsules in all carried cosmonauts to orbit between 1961 and 1963; the capsule's final flight carried Valentina Tereshkova, who became the first woman in space.

Related: Yuri Gagarin, first man in space (photo gallery)

Mercury (US, 1961)

During the Cold War space race, the U.S. strove to beat the Soviet Union's Vostok capsule with its own crewed vehicle in Project Mercury.

The Soviet Union met the milestone first with Gagarin's flight; three weeks later, the U.S. launched astronaut Alan Shepard on a suborbital flight aboard the Freedom 7 capsule. A crewed Mercury vehicle didn't reach orbit until John Glenn's flight in February 1962 aboard the Friendship 7 capsule.

Mercury capsules were approximately conical, with a cylindrical segment interrupting the cone's sides. When on the ground or atop a rocket, the cone stood upright and the astronaut lay on his back near the bottom; in orbit, the capsule rotated to seat the astronaut upright with a window panel more or less at eye level. The capsule's heat shield was at the astronaut's back, along the circular base of the cone.

Unusually, Mercury capsules had individual names beyond the series itself; others included Liberty Bell 7, Sigma 7 and Aurora 7. The final crewed Mercury capsule flew in 1963.

Related: Project Mercury: NASA's 1st crewed spaceflights in photos

Voskhod (USSR, 1964)

The Voskhod capsule was based heavily on the design of Vostok but adapted to carry more crewmembers, and later to facilitate spacewalking, the next milestone achievement the USSR had set its sights on.

First, the USSR needed to squeeze multiple crewmembers into the small capsule. To accomplish that, spacecraft engineers ditched the ejection seat and replaced it with stable couches and a landing system, according to NASA. Voskhod first carried humans in 1964, launching with a crew of three: a pilot, a medical doctor and a spacecraft engineer. To accommodate the tight conditions, the trio did not wear space suits.

A second version of the Voskhod capsule was adapted for a spacewalk, carrying an inflatable airlock. The USSR flew an uncrewed test mission for the vehicle, then in 1965 launched Voskhod 2, which carried two cosmonauts in pressure suits on a 26-hour flight. One of those cosmonauts, Alexei Leonov, exited the inflatable airlock and spent about 12 minutes in space, clinching the accomplishment of first spacewalk. The mission was Voskhod's last flight.

Related: In pictures: The most memorable spacewalks in history

Gemini (US, 1965)

Like the pair of Soviet vehicles, Gemini was at heart an adapted version of the Mercury capsule designed to let more astronauts tackle more advanced tasks. The larger capsule flew humans for the first time in March 1965, just a few days after the Voskhod 2 mission.

Gemini capsules were designed to carry two astronauts, rather than just one, and their primary task was to teach engineers how to dock spacecraft in orbit, which NASA believed would be necessary to land humans on the moon.

Two other vital tasks for the Gemini vehicles were extending the duration of spaceflight and permitting spacewalks. The second crewed Gemini mission, Gemini 4, lasted for four days and included the first American extravehicular activity, a 23-minute sortie by Ed White.

By Gemini 7, missions were stretching longer than a week to help scientists understand the consequences of lengthier spaceflights, according to NASA. In 1966, the program tackled the other key goal of the Gemini program, docking in space, when two Gemini 8 astronauts latched their vehicle onto an uncrewed Agena spacecraft.

The final Gemini mission, Gemini 12, launched in November 1966 and included three separate spacewalks and docking maneuvers with another uncrewed Agena. After that success, NASA deemed itself ready to start tackling lunar missions.

Related: Gemini 8: NASA's first space docking in pictures

Soyuz (USSR/Russia, 1967)

The Soyuz capsule, which still ferries cosmonauts into space today, began flying shortly after the retirement of the Voskhod vehicle. Its first crewed launch was in 1967, although that mission's sole cosmonaut was killed during reentry by a parachute malfunction.

Needless to say, Soyuz capsules flying today are not identical to those of the 1960s. (The name means "union.") The USSR and Russia have developed a total of 10 different crewed Soyuz models over the decades.

However, each of those variants has followed the same basic three-part recipe. At the center is the descent module, which astronauts sit in during launch and which is the only component to return to Earth at the end of a mission. To one side of that module is the orbital module, which includes crew living space and the docking mechanism to attach to other spacecraft. To the other side is the propulsion module, which carries fuel, engines and solar power panels.

All told, Soyuz spacecraft have made nearly 150 crewed flights since the vehicle design was introduced. The vehicle also docked with an Apollo command module in 1975 to mark the end of the Cold War space race.

Soyuz capsules have been the mainstay of Russia's long-term space exploration goals. The vehicles visited the Salyut and Mir stations for decades and still visit the International Space Station. Since the space shuttle retired in 2011, NASA astronauts have caught rides to the orbiting laboratory on Soyuz capsules along with their international colleagues.

Related: Experience a Soyuz spacecraft landing with this amazing 360-degree, VR video

Apollo/Lunar Module (US, 1968)

The Apollo program and its command module were meant to carry humans to the moon in the final leg of the Cold War space race; the vehicle was also meant to pull together lessons learned with the Mercury and Gemini capsules and further increase crew sizes.

The main crew capsule of the Apollo program, called the command module, slightly tweaked the shape of the previous vehicles, discarding the straight segment that stretched out the cone and giving the capsule a rather more squat profile.

The command module was meant to serve only as a transport vehicle, carrying three astronauts during launch, Earth orbit, lunar orbit and landing. The spacecraft that aimed at lunar landings were accompanied by separate vehicles dubbed lunar modules, which were designed to fly two astronauts only in space, to and from the moon's surface.

Apollo's first crewed launch was meant to be Apollo 1 in 1967, until disaster struck during a preflight test and a flash fire in the command module killed the mission's three crewmembers. NASA stepped back to investigate the accident and improve fireproofing on the capsule, waiting nearly two years to get back to the launch pad.

The command module successfully flew with humans on board in 1968 on a mission dubbed Apollo 7, an Earth-orbital flight to test the command module and the docking maneuvers that would be necessary on later flights.

By the milestone Apollo 11 flight that landed humans on the moon for the first time, missions consisted of three separate spacecraft: the command module, a workhorse service module and the lunar module that handled the landing itself.

The lunar module, in a first for spacecraft engineering, was designed only to operate beyond Earth, so it included no aerodynamic shaping. Instead, it was often compared to a large metallic bug. But then, in April 1970, three crewmembers on the Apollo 13 mission experienced an explosion in the service module on the third day of flight, when the spacecraft was about 200,000 miles (322,000 kilometers) away from Earth.

NASA scrambled into rescue mode and eventually, with the service module out of commission and the command module running low on power, the three astronauts piled into the lunar module and headed for the scenario the vehicle hadn't been designed for: returning to Earth. The lifeboat plan worked, carrying all three astronauts safely home.

The last Apollo mission, Apollo 17, flew in December 1972; the Apollo capsule made its final flight in 1975.

Related: Building Apollo: Photos from moonshot history

Space Shuttle (US, 1981)

After the Apollo program ended in 1972, NASA took a break from human spaceflight for nearly a decade, not launching another crewed vehicle until the early 1980s. That vehicle was the space shuttle, the first reusable crewed spacecraft. NASA built five separate shuttles that reached space on a total of 135 crewed missions between 1981 and 2011.

The shuttles (technically known as the Space Transportation System) also marked the first big design jump in crewed spacecraft. The main shuttle body, which looks rather like a plane, was the orbiter itself. During launch, that orbiter was joined by three other pieces, one massive fuel tank painted a distinctive rust orange (the only component not reused) and two thinner white solid rocket boosters.

The orbiters included two decks, an airlock and a massive cargo bay. Most crews included seven astronauts. At the end of a mission, the orbiter returned to Earth, taking the heat from the reentry process on its protective belly tiles.

Of the five shuttles, two were destroyed during fatal accidents. First, in January 1986, Challenger suffered an anomaly during launch; then, in February 2003, Columbia fell to pieces during reentry. Each disaster killed all seven astronauts on board and prompted internal investigations at NASA, and the legacy of these two flights has contributed to NASA's deeply rooted safety culture.

NASA decided to retire the three remaining but aging shuttles in 2011.

Related: 10 amazing space shuttle photos

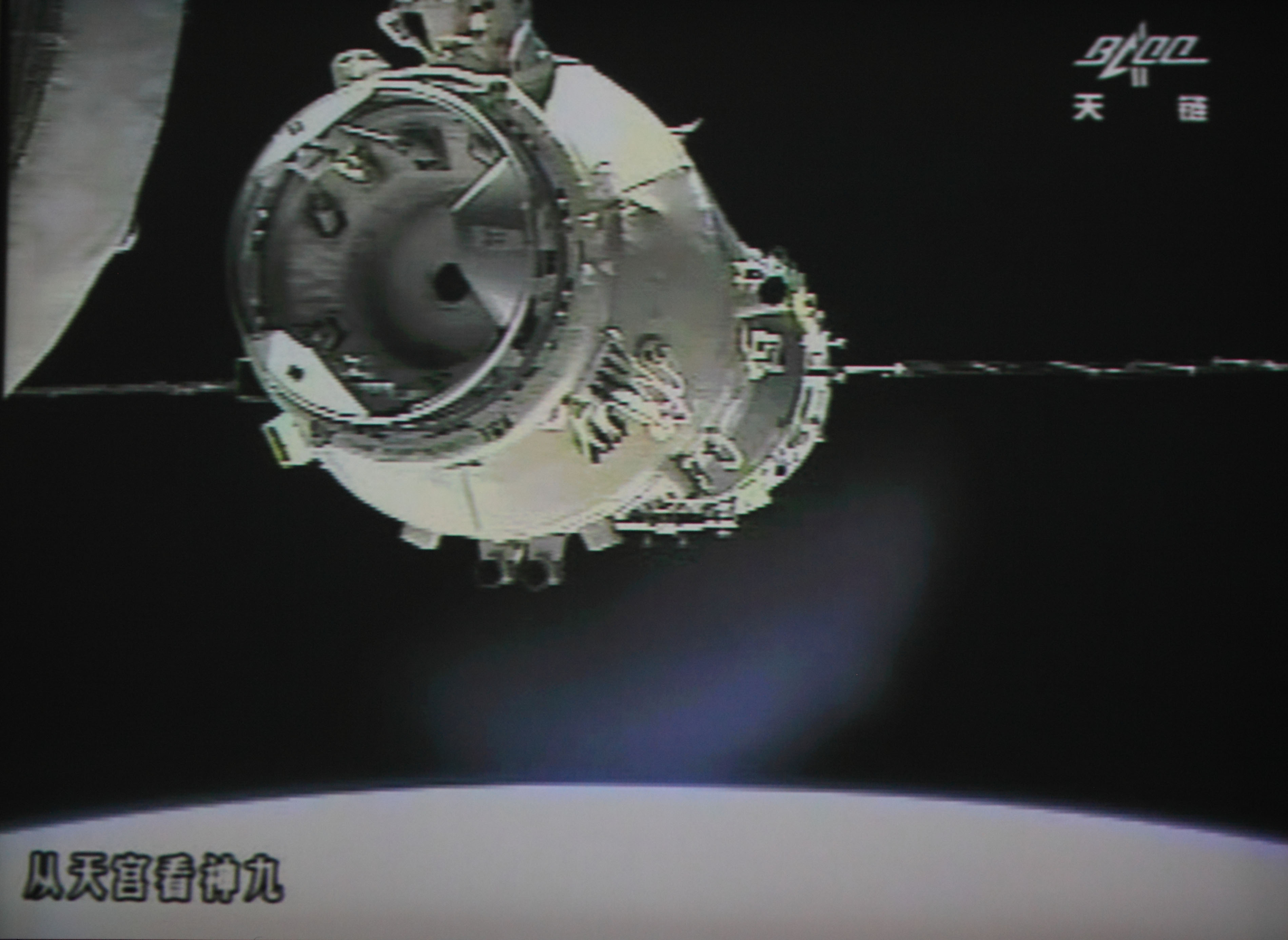

Shenzhou (China, 2003)

China joined the crewed vehicle owners with its Shenzhou vehicle line. The name translates as "divine vessel," according to NASA.

The Shenzhou spacecraft are built in a rather similar manner to the Russian Soyuz vehicles, with a three-part design of orbital, reentry and service modules. The first crewed Shenzhou to fly launched in 2003 and made China the third country with the capability to launch humans to orbit. That flight carried one taikonaut, the Chinese term for an astronaut, who orbited for nearly a day.

China's next crewed flight carried two taikonauts; the third flight carried three taikonauts and included a spacewalk. Then China pivoted the vehicle's focus to rendezvous with the nation's first two independent space stations.

A total of six Shenzhou spacecraft have carried humans, with the most recent launch occurring in 2016.

Related: In photos: Tiangong-1, China's space station fell to Earth

Crew Dragon (US, 2020)

SpaceX's Crew Dragon capsule, scheduled to launch two NASA astronauts to the International Space Station on May 30 (after a delay due to bad weather on May 27), will — if all goes well — become the first commercially built vehicle to carry humans to space.

Crew Dragon is based heavily on SpaceX's long-flying cargo ship, the Dragon, which the company built under NASA's commercial cargo delivery program and which made its first full-fledged delivery run in 2012.

Crew Dragon was built under the agency's commercial crew program, and made a successful uncrewed test flight to the space station in March 2019.

Two key modifications for the crewed version are that the spacecraft docks itself to the International Space Station, rather than relying on being snagged by the laboratory's robotic arm, and, of course, the addition of life-support systems. Crew Dragon can seat up to seven people, according to SpaceX.

Related: How SpaceX's Crew Dragon Demo-2 mission will work in 13 steps

Suborbital bonus

Two types of vehicles have also carried astronauts into space on suborbital missions. These are much shorter flights, but do cross the altitude of 62 miles (100 kilometers) that is currently considered to represent the boundary of space.

NASA's X-15 test plane accomplished the feat during the 1960s. Although the vehicles flew a total of 199 missions, most didn't cross the boundary. The highest altitude the plane reached was 67 miles (108 km). The vehicle is considered a crucial stepping stone to the space shuttle, since it proved that a plane-like vehicle could survive atmospheric reentry.

Related: Photos: X-15 rocket plane Reaches space in test flights

Much later, SpaceShipOne was the first commercial vehicle to officially reach space, in 2004. The vehicle and its successor, SpaceShipTwo, now owned by Virgin Galactic, are designed for suborbital flights only, not orbital flight, and launch in the air, after being lifted by a carrier plane.

SpaceShipOne retired shortly after its historic flight; SpaceShipTwo made crewed tests beginning in 2010 and carried the first non-pilot passenger to space in 2019. Virgin Galactic's latest SpaceShipTwo vehicle, called VSS Unity, is in the final phases of its test campaign and could start flying operational, passenger-carrying missions as early as this year.

Related: In photos: Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo Unity's 4th powered test

Stay tuned

While the pace of new vehicle introductions has been slow in recent years, a few other orbital and suborbital vehicles are checking off developments toward crewed flights.

SpaceX's counterpart in NASA's commercial crew program, Boeing, launched an uncrewed test flight of its Starliner vehicle to the space station in December 2019, but failed to dock to the orbiting laboratory. The company plans to make another such flight later this year before attempting a crewed flight. Unlike Crew Dragon, the Starliner capsule was designed from scratch.

Internationally, China tested a new crewed vehicle, as yet unnamed, during an uncrewed flight early in May. That capsule is meant to facilitate the country's plans to build a new, three-module space station.

Closer to Earth, Blue Origin is testing what it intends to become a crewed tourist vehicle for suborbital flights, New Shepard. The company, started by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, has flown a dozen uncrewed flights and hoped to launch humans last year.

Related: Boeing's 1st Starliner flight test in photos

- Visions of the future of human spaceflight

- The most extreme human spaceflight records

- Spaceships of the world: 50 years of human spaceflight

Editor's note: This story has been updated. Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.