Massive eruption from icy volcanic comet detected in solar system

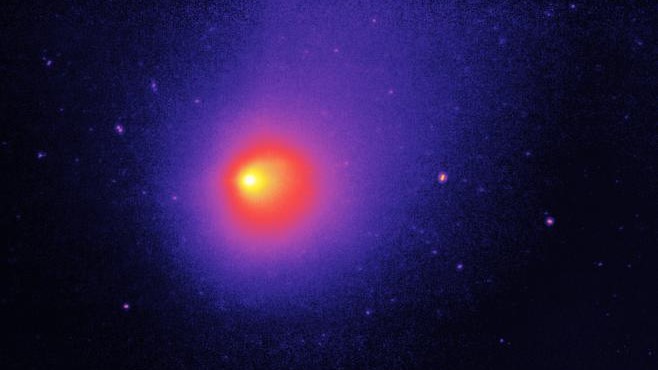

Astronomers observed a major eruption from a volcanic comet flying through the solar system, likely spewing more than 1 million tons of debris into space.

A bizarre, volcanic comet has violently erupted, spewing out more than 1 million tons of gas, ice and the "potential building blocks of life" into the solar system.

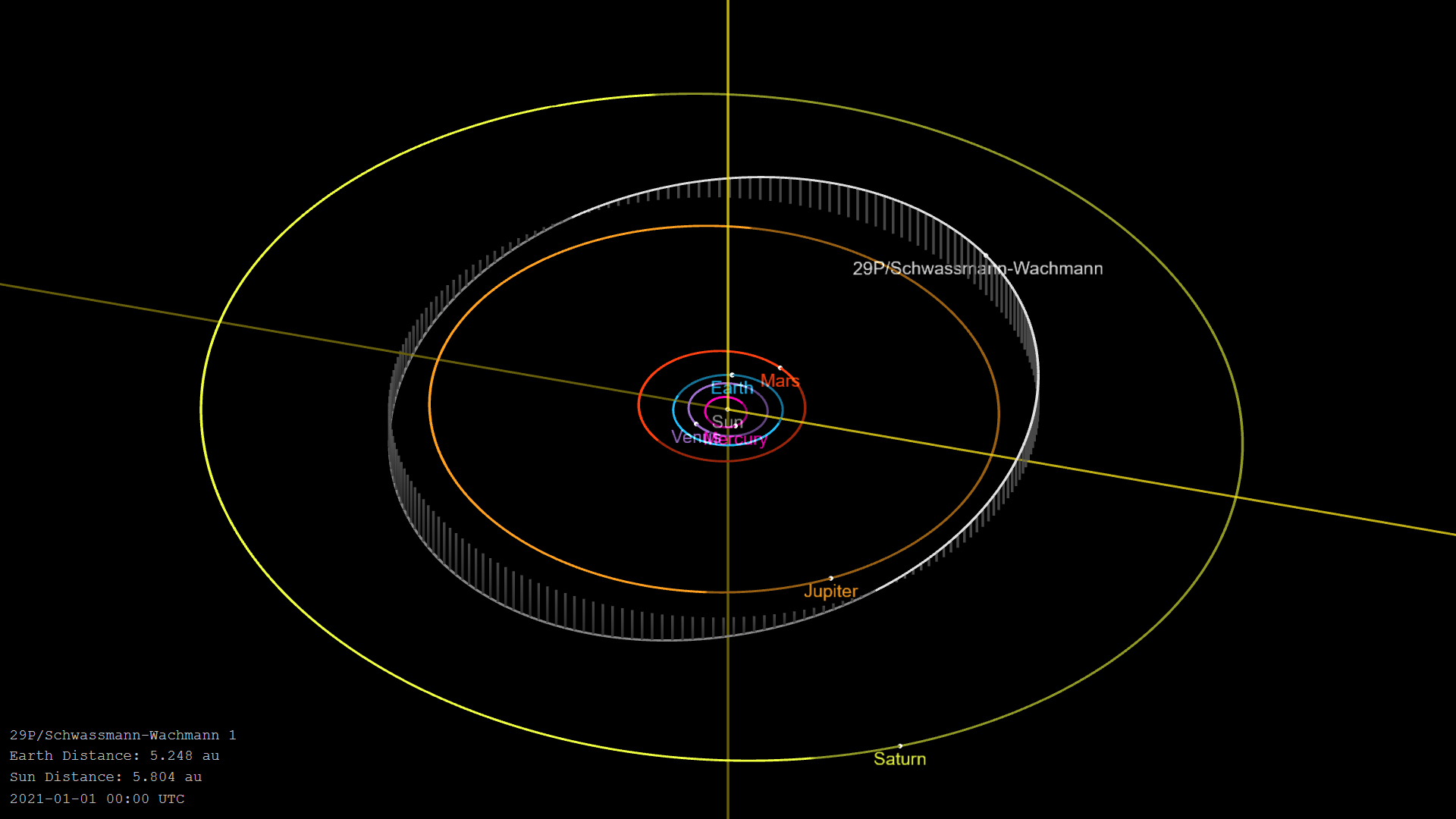

The volatile comet, known as 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann (29P), is around 37 miles (60 kilometers) wide and takes around 14.9 years to orbit the sun. 29P is believed to be the most volcanically active comet in the solar system. It is one of around 100 comets, known as "centaurs," that have been pushed from the Kuiper Belt — a ring of icy comets that lurk beyond Neptune — into a closer orbit around the sun between those of Jupiter and Neptune, according to NASA.

On Nov. 22, an amateur astronomer named Patrick Wiggins noticed that 29P had drastically increased in brightness, according to Spaceweather.com. Subsequent observations made by other astronomers revealed that this spike in luminosity was the result of a massive volcanic eruption — the second largest seen on 29P in the last 12 years, according to the British Astronomical Association (BAA). The largest eruption during this time was a huge outburst in September 2021.

An eruption of this size is "pretty rare," Cai Stoddard-Jones, a doctoral candidate at Cardiff University in the U.K. who took a follow-up image of 29P's eruption, told Live Scence. "It's [also] difficult to say why this one is so big.".

The explosion was followed by two smaller outbursts on Nov. 27 and Nov. 29, according to BAA.

Related: Watch the biggest-ever comet outburst spray dust across the cosmos

Unlike volcanoes on Earth, which eject scalding-hot magma and ash from the mantle, 29P spits out extremely cold gases and ice from its core. This unusual type of volcanic activity is known as cryovolcanism, or "cold volcanism."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cryovolcanic bodies, which include a handful of other comets and moons in the solar system such as Saturn's Enceladus, Jupiter's Europa and Neptune's Triton, have a surface crust surrounding a mainly solid icy core, Richard Miles, a BAA astronomer who has studied 29P, told Live Science. Over time, radiation from the sun can cause the comets' icy interiors to sublime from solid to gas, which causes a buildup of pressure beneath the crust. When radiation from the sun also weakens the crust, that pressure causes the outer shell to crack, and cryomagma shoots out into space.

The cryomagma from comets like 29P is mainly composed of carbon monoxide and nitrogen gas, as well as some icy solids and liquid hydrocarbons, which "may have provided some of the raw materials from which life originated on Earth," NASA representatives wrote.

The ejecta from the most recent eruption of 29P stretched up to 34,800 miles (56,000 km) away from the comet and is traveling at speeds of up to 805 mph (1,295 km/h), according to BAA. The plume "probably comprised more than one million tons of ejecta," Miles added.

Photographs of the erupting comet also show that the plume formed an irregular Pac-Man-like shape, which suggests the eruption originated from a single point or region on the comet's surface, according to Spaceweather.com.

These observations back up previous research that suggests 29P's eruptions are linked to its rotation. Miles and Stoddard-Jones believe that the comet's slower rotation causes solar radiation to absorb more unevenly on the comet, triggering the eruptions. So far eruptions from the comet tend to match up with its 57-day rotation period, the researchers said.

Related: Volcanic eruptions on the moon happened much more recently than we thought

Researchers also suspect that 29P's most explosive eruptions follow a cycle based on its orbit around the sun. A number of large eruptions were detected between 2008 and 2010, and now two massive explosions have occurred within the last two years, Miles said. It is therefore likely that there will be least one more major eruption from 29P by the end of 2023, he added.

However, it is less clear how this longer eruption cycle is occurring, because unlike most other comets, which get closer to the sun during a specific period of their orbits, 29P has a largely circular orbit, meaning it never gets much closer to the sun than its average distance, Stoddard-Jones said.

29P has largely been ignored by the astronomical community since its discovery in 1927, but as new evidence emerges about its unusual volcanic activity it is starting to be taken more seriously, Miles said. "Clearly there is something new to be discovered in studying 29P."

The James Webb Space Telescope is scheduled to take a closer look at 29P early next year, he added.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.