Scientists may have cracked the mystery of da Vinci’s DNA

Scientists say they could be closer to uncovering a genetic basis for the artist's talent.

Leonardo da Vinci — the great Renaissance artist, inventor and anatomist — has 14 living male relatives, a new analysis of his family tree reveals. The new family tree could one day help researchers determine if bones interred in a French chapel belong to the Italian genius.

Historians Alessandro Vezzosi and Agnese Sabato have spent more than a decade tracing the genealogy of the famed "Mona Lisa" painter. Their map stretches across 690 years, 21 generations and five family branches, and will be vital in helping anthropologists sequence the DNA of da Vinci by sequencing the DNA of his descendants, the researchers say.

Related: Leonardo da Vinci's 10 best ideas

Beyond establishing the identity of his possible remains, sequencing the artist's DNA could also give scientists a better understanding of "his extraordinary talents — notably, his visual acuity, through genetic associations," claim representatives from the Leonardo Da Vinci DNA Project, an initiative that aims to use the genetic information to create 3D images of da Vinci through a process called DNA phenotyping.

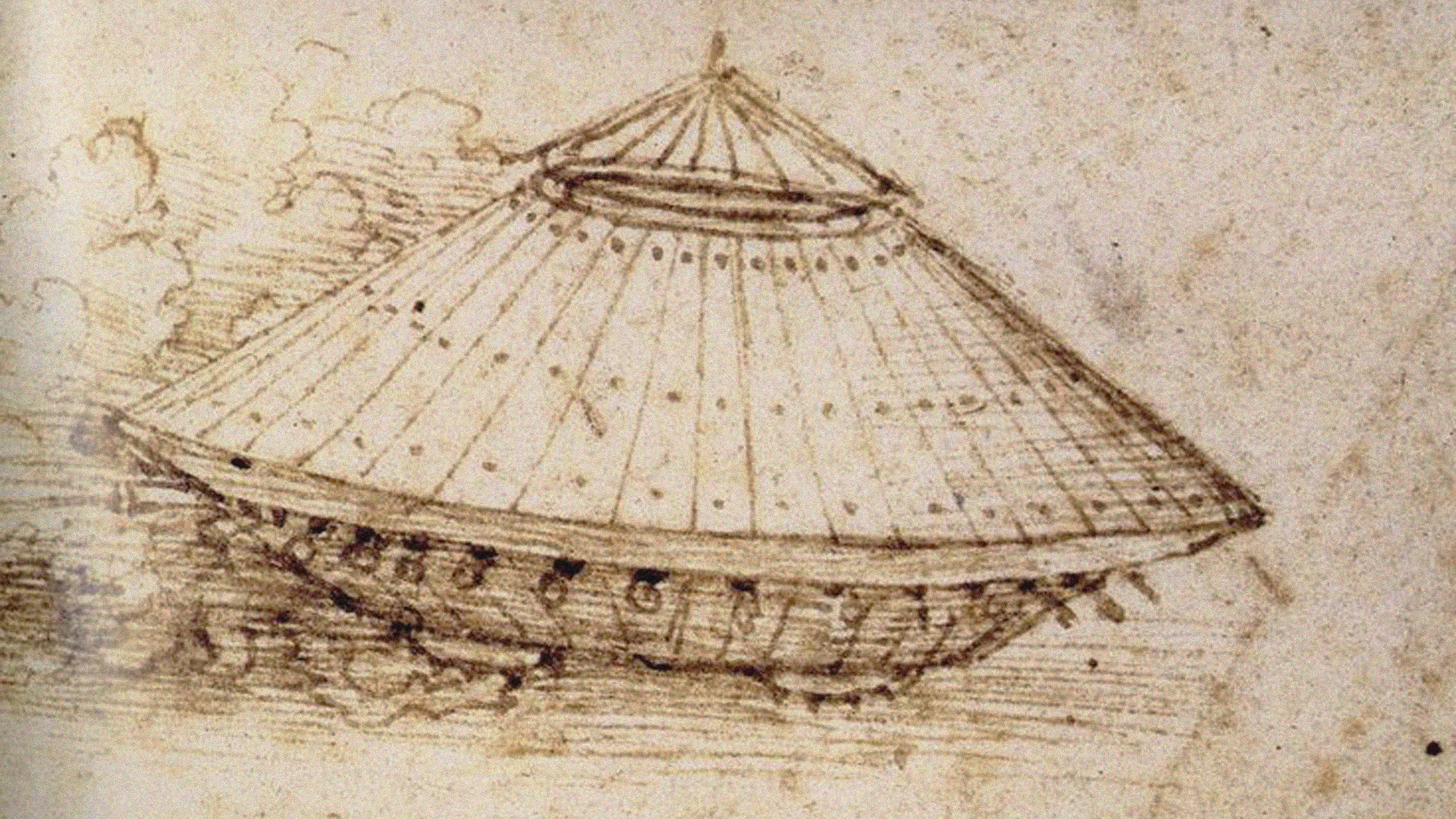

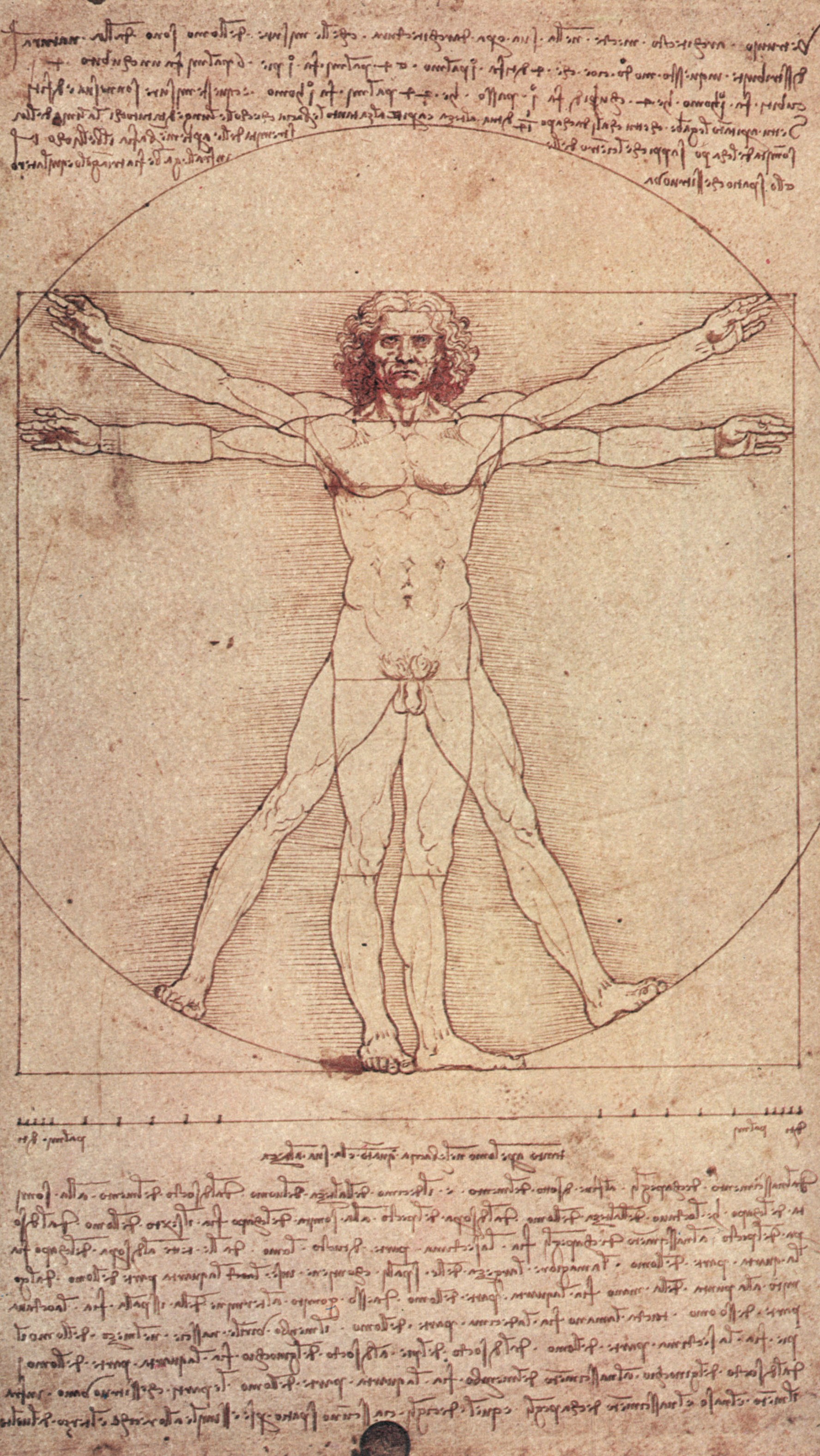

Da Vinci was a painter, architect, inventor, anatomist, engineer and scientist. Primarily self-educated, he filled dozens of secret notebooks with fanciful inventions and anatomical observations. To accompany famous sketches such as the "Vitruvian Man", da Vinci would write messages coded into his own shorthand, mirrored back to front to hide his studies from prying eyes. Along with detailed drawings of human anatomy, taken from observations of dissected cadavers, his notebooks contain designs for bicycles, helicopters, tanks and airplanes.

In a new study, Vezzosi and Sabato used historical documents from archives alongside direct accounts from surviving descendants to trace the five branches of the da Vinci family tree. According to the historians, Leonardo was part of the sixth generation of da Vincis.

Researching da Vinci’s family history is difficult because only one of his parents can be properly traced. Born out of wedlock in the Tuscan town of Anchiano, Leonardo da Vinci was the son of Florentine lawyer Ser Piero da Vinci and a peasant woman named Caterina. Research by Martin Kemp, an art historian at Oxford University, suggests that Caterina was a 15-year-old orphan at the time of da Vinci's birth, Live Science previously reported. At age 5, the young da Vinci was taken to his family estate in the town of Vinci (from which his family took their surname ) to live with his grandparents.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When da Vinci died on May 2, 1519, at age 67, he had no known children, and his remains were lost, meaning there was no reliable DNA to analyze. As a result, parts of his ancestry have become shrouded in mystery.

Leonardo's original burial was recorded at the chapel of Saint-Florentin at the Chateau d'Amboise, a manor house in France's Loire Valley. The chapel was left to ruin after the French Revolution and later demolished. Contemporaneous accounts allege that a full skeleton was exhumed from the site and moved to the nearby Saint-Hubert chapel, but whether or not they are actually Leonardo’s bones remains a mystery.

The new family tree, which starts in 1331 with family patriarch Michele, revealed 14 living relatives with a wide variety of occupations, including office workers, a pastry chef, a blacksmith, an upholsterer, a porcelain seller and an artist.

The researchers will determine whether the human remains from the Loire Valley chapel belong to da Vinci by comparing the Y chromosome in those bones to the Y chromosome belonging to da Vinci’s male relatives. The Y chromosome is passed from father to son and remains virtually unchanged for as long as 25 generations, according to the researchers.

In addition, finding fragments of da Vinci's genetic code could help art historians verify the authenticity of artworks, notes and journal entries supposedly created by the Italian Renaissance man by comparing his discovered DNA with DNA traces found on the pieces.

The researchers published their findings July 4 in the journal Human Evolution.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.