What are the deepest spots in Earth's oceans?

What types of sea creatures live at these depths?

There are deep realms on our planet that seem almost extraterrestrial. Translucent fish flit back and forth while strange, flower-like crinoids sway in the water. But of all the submarine canyons and trenches out there, what are the deepest, darkest spots in each of the world's five oceans?

The deepest place in the Pacific Ocean (and on Earth) is the Mariana Trench. The trench's deepest point is the Challenger Deep near the U.S. territory of Guam — a plunge that's almost 36,000 feet (10,973 meters) below the water's surface, according to a 2019 study published in the journal Earth-Science Reviews.

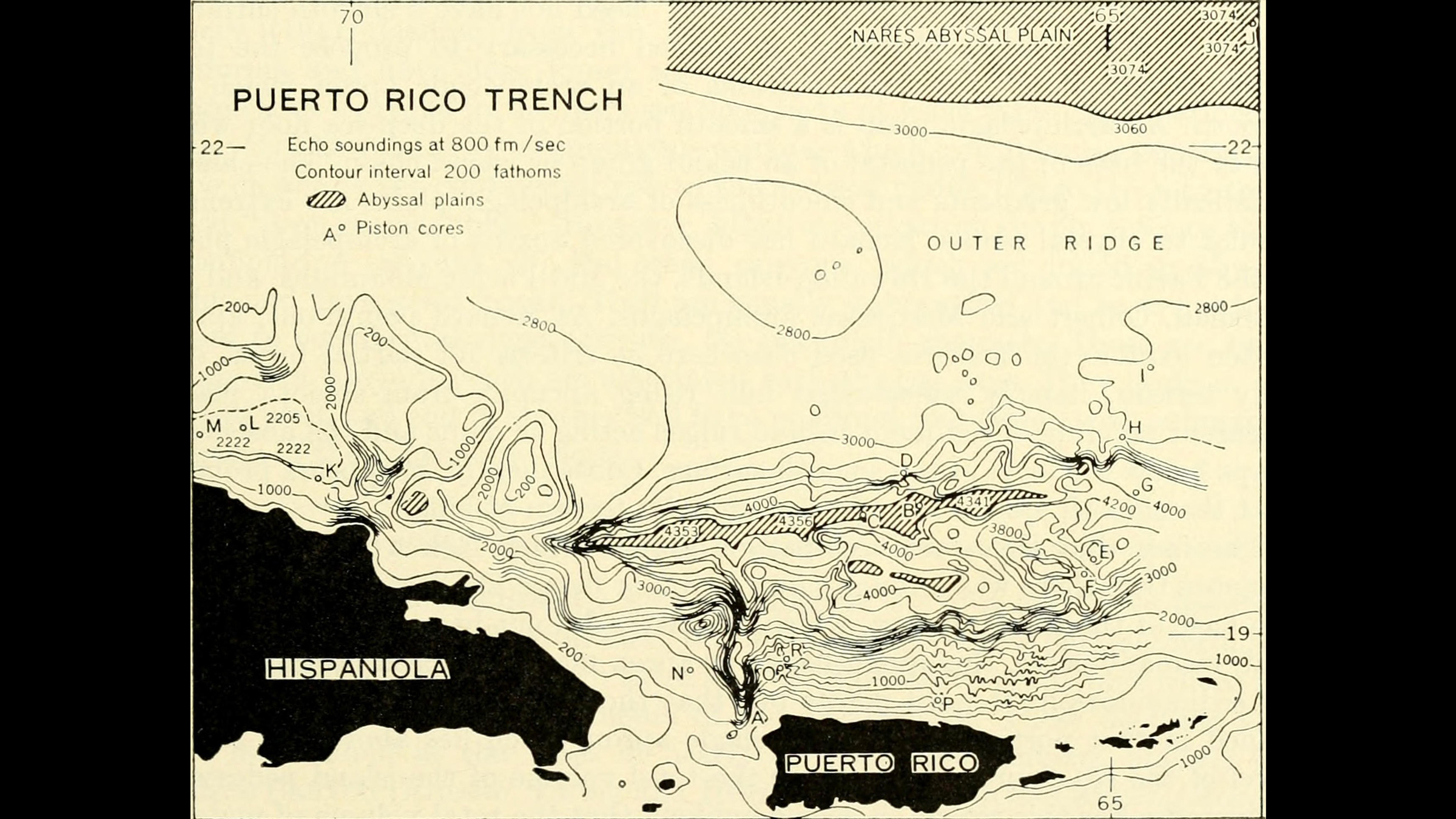

The deepest region in the Atlantic Ocean is the Milwaukee Deep in the 27,585-foot-deep (8,408 m) axis of the Puerto Rico Trench. Coming in at 23,917 feet (7,290 m) deep is a nameless region at the bottom of the Indian Ocean. The Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean) goes all the way down to 24,229 feet (7,385 m) in the South Sandwich Trench, and the Arctic Ocean goes down to 16,000 feet (4,877 m) deep at Molloy Deep in the Fram Strait.

Such areas are far from the reach of the sun and may appear to be nothing but gaping mouths of impenetrable darkness. But what do scientists know about these final frontiers?

Related: Why are there so many giants in the deep sea?

The Mariana Trench

The Mariana Trench is a 1,580-mile-long (2,542 kilometers) oceanic abyss where several of the planet's deepest points can be found.

Only 27 people have ever been to the Challenger Deep, the Mariana Trench's deepest point: The first to go there were explorer Jacques Piccard and Navy Lt. Don Walsh, who ventured there in 1960.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mackenzie Gerringer, who went on an expedition in 2014 to the 34,448-foot-deep (10,500 m) Sirena Deep (one of the other deepest parts of the trench) with colleagues from the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, observed the challenging conditions that exist in the darkness.

"There's no sunlight," she told Live Science in an email. "Temperatures are cold, typically about 1-2°C [33.8 to 35.6 degrees Fahrenheit]. Pressures are high, up to 15,000 pounds per square inch [1,034 bars] at the ocean's greatest depths." Gerringer is now an assistant professor of biology at the State University of New York (SUNY) College at Geneseo.

Despite the extreme conditions, life exists in the deepest parts of our planet's seas. Jeff Drazen, a professor of oceanography at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, observed that the types of creatures that thrive at extreme depths tend to be similar, even though different species might be unique to different regions. He explained that certain creatures appear at specific depths.

"We found that life changed dramatically with depth," he said. "The bottom of a species' depth range is controlled by adaptations to pressure, and the top of its range may be controlled by predation or competition."

During Gerringer's expedition, she, Drazen and colleagues sent probes to the bottom of Sirena Deep and discovered a new species of Mariana snailfish. The newfound critter was a hadal snailfish, named for the hadal zone, the part of the ocean that is between about 19,700 feet and 36,000 feet (6,000 to 10,970 m) deep and only occurs in marine trenches.

Critters like this are specially adapted to survive in the deep. According to Gerringer, extreme pressures push against the body and impair enzymes and proteins. Mariana snailfish and other hadal species are equipped to handle this with enzymes that operate more effectively under extremely high pressure. They also produce a molecule known as TMAO (trimethylamine N-oxide) to keep the pressure from messing with the proteins in their bodies.

What Gerringer and Drazen observed in the Mariana Trench mirrors what is generally seen in abyssal and hadal zones across Earth. In the Mariana Trench,16,000 feet (488 m) down, cusk eels and rattail fish swam among decapod shrimp. As probe cameras dove deeper, these species gave way to snailfish and giant amphipods, and deeper still, different species of mostly smaller amphipods and shrimp appeared. The deepest at which any fish were seen was 26,250 feet (8,000 m).

The Puerto Rico Trench

Off the coast of Puerto Rico and south of the tip of Florida, the Puerto Rico Trench — like most deep-sea trenches — is evidence of an ancient subduction event.

"Most of these hadal habitats are trenches that form via subduction, where one tectonic plate slides under another, creating a deep valley," Gerringer said.

Shifting tectonic plates also explain the presence of a group of volcanic islands scattered nearby, as subduction is the same kind of tectonic activity that can cause magma to rise up from beneath Earth's crust. Those are not the only volcanoes around this trench. Deep underwater, a volcano that erupted in mud was found close to the 26,000-foot-depth (8,000 m) mark, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Areas around this trench are prone to earthquakes and tsunamis because of subduction. There is even a fault in the Puerto Rico Trench that looks eerily like a submerged version of the San Andreas Fault.

The deepest part of the trench is the Milwaukee Deep, which explorer Victor Vescovo dived to in a crewed submersible in 2018 (Vescovo had previously gone down to the Mariana Trench and was the first person to ever dive to the Challenger Deep twice).

The Java Trench and the South Sandwich Trench

The deepest parts of the Indian Ocean's Java Trench and the Antarctic Ocean's South Sandwich Trench were both determined by the Five Deeps Expedition (FDE) in 2021, according to the British Geological Survey. Before the expedition, these unnamed regions had been mostly unexplored — the South Sandwich Trench, the only hadal zone on Earth that experiences sub-zero temperatures, had not been explored at all before this mission.

The expedition's researchers explored the hidden depths of the ocean by sending down remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). The team used a Deep Submergence Vehicle (DSV) and three additional landers — robots carrying multiple instruments, such as sensors, that fall to the bottom and probe the seafloor. The team's findings were published in the Geoscience Data Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society.

In the Java Trench, cameras on the FDE landers observed hadal snailfish, sea cucumbers and weird-looking lifeforms, such as a sea squirt that floated in the dark waters like a ghostly balloon. Another FDE study published in Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography highlighted the fauna in the South Sandwich Trench. In these freezing waters, researchers found snailfish amphipods, brittle stars, sea cucumbers, sponges and crinoids.

The Fram Strait

Going from the Antarctic to the Arctic Ocean, the Five Deeps Expedition next investigated the Molloy Deep in the Fram Strait, between the east of Greenland and the Svalbard islands off the northern coast of Norway. No other mission had ever seen the bottom of the Molloy Deep before.

In the Fram Strait, fluctuations in levels of fresh and salt water impact populations of phytoplankton and other microbes. Climate change has impacted the Arctic Ocean the most out of any of the world's five oceans, and the thickness of sea ice has been steadily decreasing since 1990.

Few creatures live in the Molloy Deep. It is essentially an enormous crater, and organic matter gathers and falls down the sides, but there are not many creatures that inhabit this barren region, scientists at the Maier-Kaiser Lab (which is part of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts) found when they searched it for larvae. The only animal that has been caught on camera there is a type of deep-sea sea cucumber known as a sea pig.

While these deep-sea environments around the world may seem very remote, they are still impacted by human activity. Gerringer is concerned that the effects of climate change, such as the melting of Arctic ice, and pollution may make their way from the bottom to the surface. There is already an amphipod found in the Mariana Trench named Eurythenes plasticus because of microplastics found in its stomach. It doesn't end there. Vescovo found a plastic bag and candy wrappers in the same trench.

"The deep sea is closely connected to the surface oceans," she said. "Human activities such as plastic pollution and climate change are already influencing deep-sea habitats and it's important that we understand, appreciate, and protect these ecosystems."

Elizabeth Rayne is a contributing writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in SYFY WIRE, Forbidden Futures, Grunge and Den of Geek. She holds a bachelor of arts in English literature from Fairfield University in Connecticut and a master's degree in English writing from Fordham University, and most enjoys writing about space, along with biology, chemistry, physics, archaeology and paleontology.