Defending Earth against dangerous asteroids: Q&A with NASA's Lindley Johnson

A major asteroid or comet strike could cause extensive devastation and profoundly affect life on Earth.

It's a cosmic roll of the dice. There's no doubt that a major asteroid or comet strike could cause extensive devastation and profoundly affect life on Earth.

The largest hit in recent times was the object that exploded over Tunguska, Siberia, in June 1908 with an energy impact of five to 15 megatons. Then there was that spectacular and destructive airburst in February 2013 over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk. The Chelyabinsk explosion generated a shock wave that shattered windows on the ground, and the resulting flying glass shards injured more than 1,000 people.

While these run-ins are few and far between, those in the know call them wakeup calls.

Infographic: Huge Russian meteor blast is biggest since 1908

Thwarting an incoming object that has Earth in its crosshairs will mean deflecting or disrupting the hazardous object. That's a task of planetary defense, an "applied planetary science" to address the near-Earth object (NEO) impact hazard.

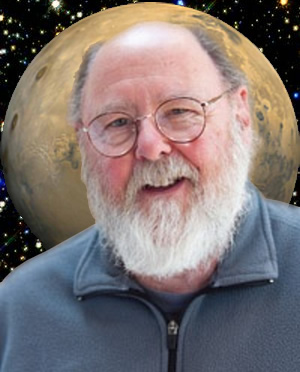

Lindley Johnson is NASA's Planetary Defense Officer and program executive of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office. An email from him includes the on-the-job line: "Hic Servare Diem," Latin for "Here to Save the Day."

Space.com caught up with Johnson to discuss recent events and what's on the planetary-defense agenda in the coming year.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Space.com: What's the impact of the Dec. 1 loss of the Arecibo Observatory's 305-meter telescope on your planetary radar efforts for NEO observations?

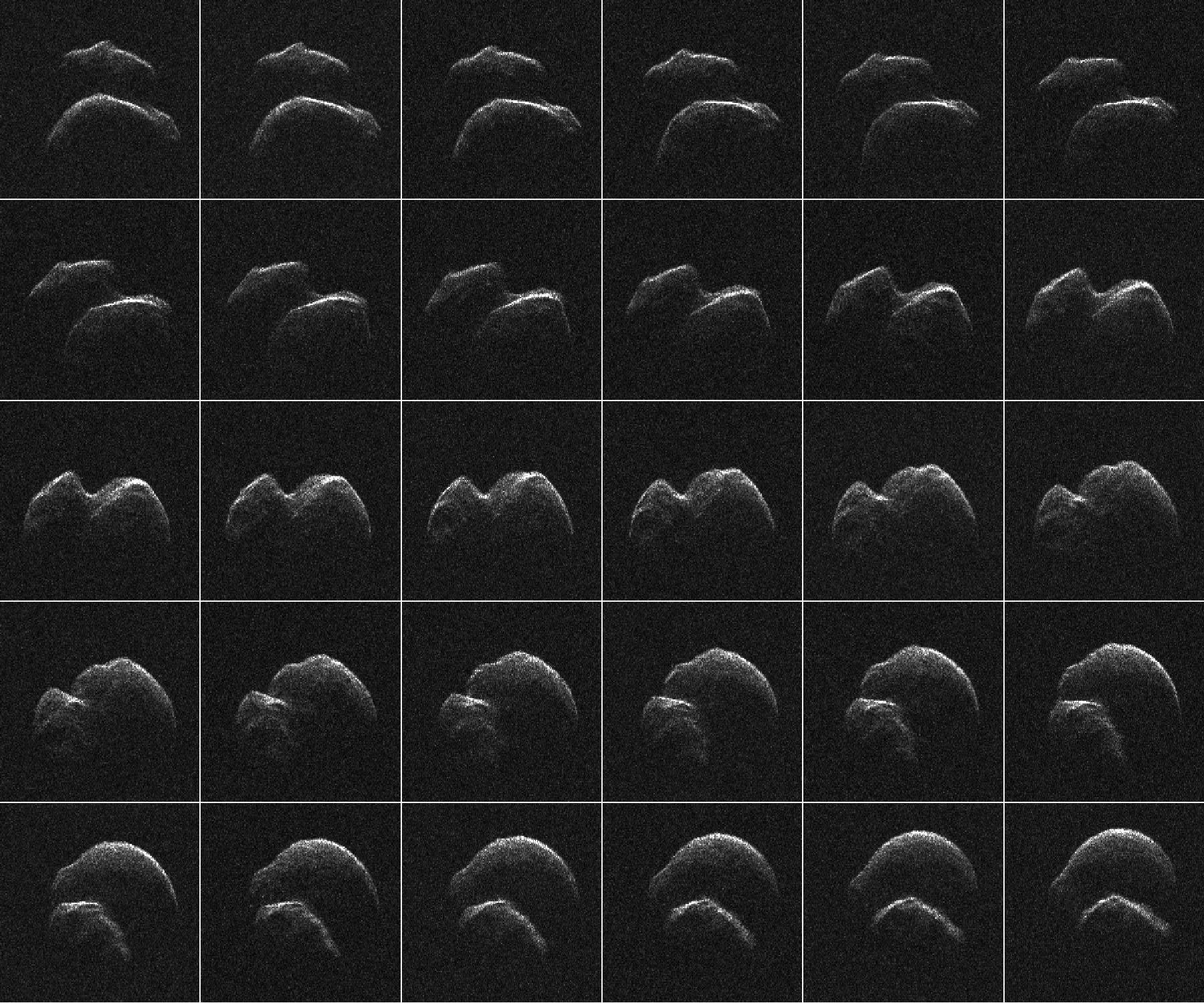

Johnson: The National Science Foundation made the hard decision that it needed to be decommissioned for safety reasons and brought down. But the telescope decided to do it on its own. Its planetary radar observation isn't unique, as we have it at our Goldstone [Solar System Radar in California's Mojave Desert] too. What was unique about Arecibo was the size of the dish and the power it generated, which gave it a longer range than we have at Goldstone.

Space.com: So we have lost capability?

Johnson: We have lost that capability, but we haven't lost planetary radar capability. But it does make Goldstone a more critical capability for us than it was. We did have some overlap and redundancy prior to loss of Arecibo, but now we have Goldstone. I think not only NASA but other agencies as well will soon engage in a study of what is the future for our planetary radar capability. I think the loss of Arecibo will provide the incentive to get that together, a concerted effort on the part of several agencies.

Related: Potentially dangerous asteroids (images)

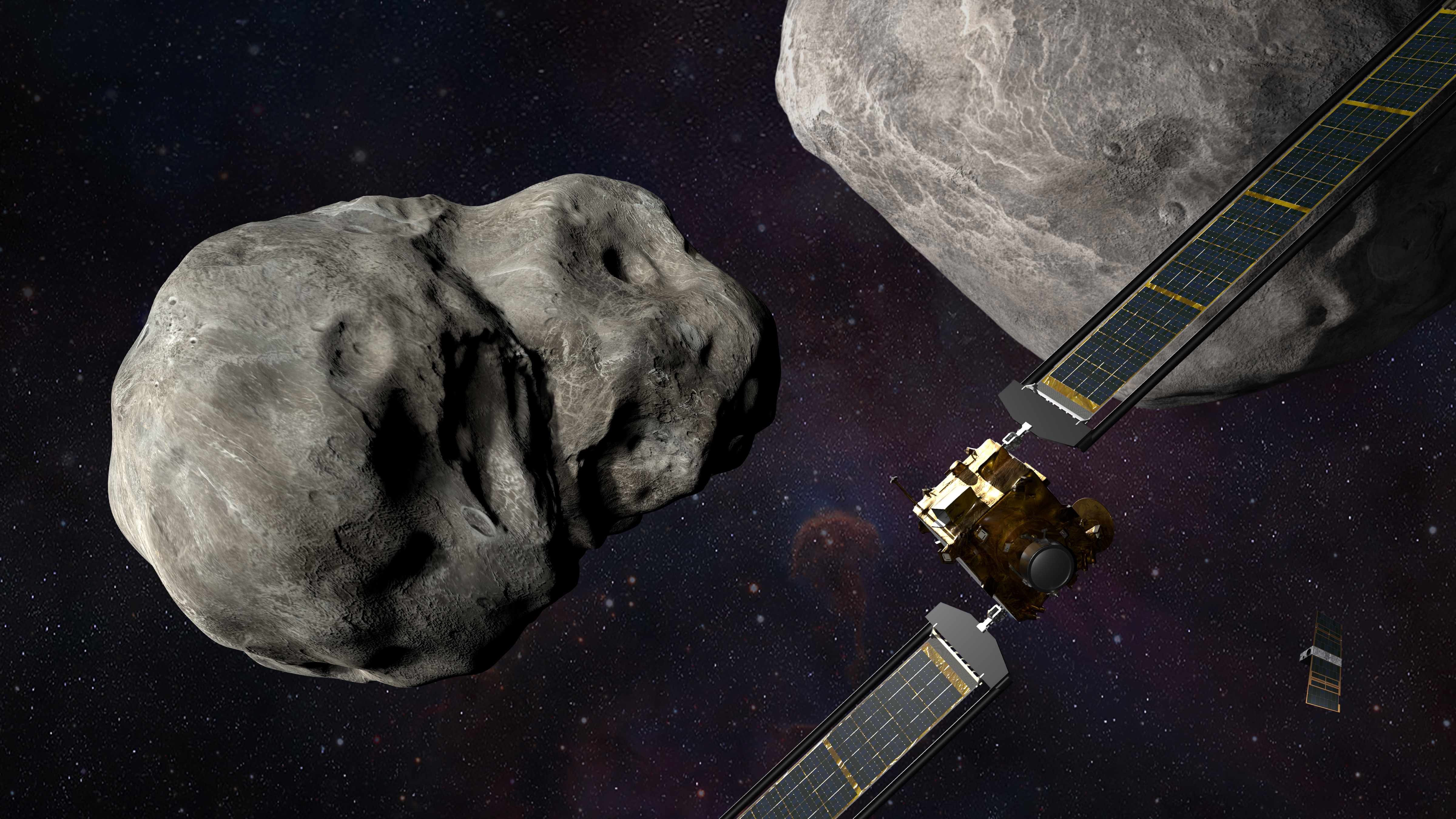

Space.com: How is the launch next year of NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) coming along?

Johnson: It's about two-thirds of the way through its integration and test now at the Applied Physics Laboratory [APL, at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland]. It is beginning to look like a real spacecraft. But there certainly have been challenges with COVID-19 and delivery by suppliers of all the parts. One of the remaining big pieces still to be delivered is the rollout solar arrays. But the integration schedule has been rearranged. Things are looking positive all the way through the testing that's going on. We're in pretty good shape to get DART shipped out to Vandenberg [Air Force Base in California] to meet the end-of-July launch.

Space.com: Any update on the Italian Space Agency's Light Italian Cubesat for Imaging of Asteroid, the LICIACube built to witness DART's impact?

Johnson: They've had their challenges too, maybe even more so. We're hoping they will be able to stay on schedule. LICIACube could be integrated at APL, or it could also be integrated out at Vandenberg if they need to.

Space.com: As NASA's first planetary defense mission, what do you hope to learn from DART?

Johnson: It will confirm for us what the viability of the kinetic impactor technique is for diverting an asteroid's orbit and determine that it remains a viable option, at least for smaller-sized asteroids, which are the most frequent impact hazard.

Space.com: You have been engaged in a series of "table top" exercises involving the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and other organizations about the nature, risk and what to do given an Earth encounter with an asteroid or comet impact. What's their value to your work?

Johnson: There will definitely be more coming, and possibly next year. We do introduce different scenarios, like how much time before impact do you have? Or what's the size of the object? To date, the exercises have been done with a relatively small community. I think in a future exercise, our main objective is to have a broader community of the NEO Impact Threat Emergency Protocols Working Group take part, representation from a number of other agencies that have not been involved in previous exercises. That working group was formed in early 2019 to work on Goal 5 actions in the National NEO Strategy and Action Plan.

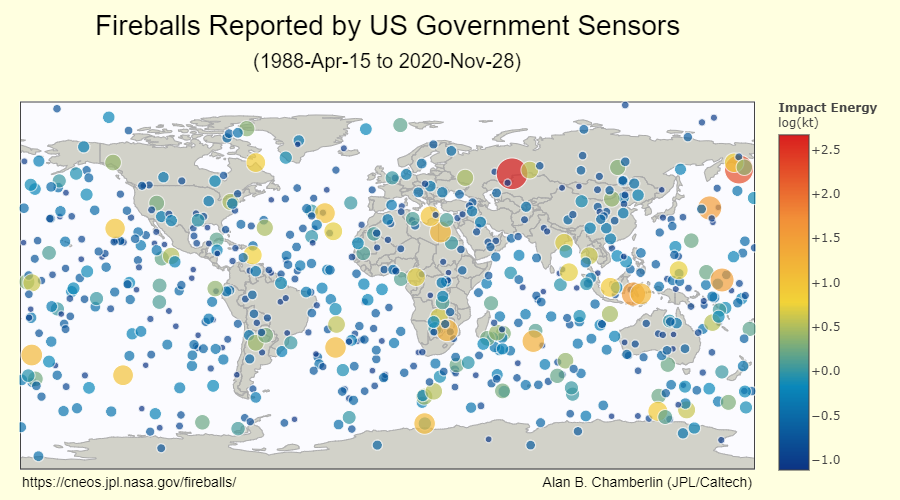

Space.com: The JPL Center for NEO Studies is NASA's center for computing asteroid and comet orbits and their odds of Earth impact. Fireball and bolide data is included on their website, some of which is gleaned from classified military satellites. How is that data exchange between NASA and the military going?

Johnson: The pathways and the capabilities are more straightforward than it used to be. We are still working on making it faster, more automated. Through this last year some of it was somewhat manual, with data delayed longer than we would like it to be. If you check out the website, you'll see a steady addition of events into our database.

Space.com: You would want to obtain that data far sooner?

Johnson: Within hours of the event, if not quicker.

Space.com: Asteroid samples brought back to Earth — be they from Japan's Hayabusa2 spacecraft and NASA's OSIRIS-REx — how valuable are they to your planetary defense office?

Johnson: They certainly do help us understand the nature and composition of these objects. Getting these spacecraft out there to observe them up close is part of a step-by-step approach, from remote sensing of them … and then collecting a sample for lab analysis here on Earth. It confirms what we think we know about an asteroid's composition.

That's of course of great interest to the scientific community. But it's also of value in understanding how mitigation techniques might be more effective. For remote sensing of these objects, you are never sure whether the lines and squiggles are being interpreted correctly. When you get up close, you can confirm a number of things. So it's kind of a bootstrap approach.

Related: The greatest asteroid encounters of all time!

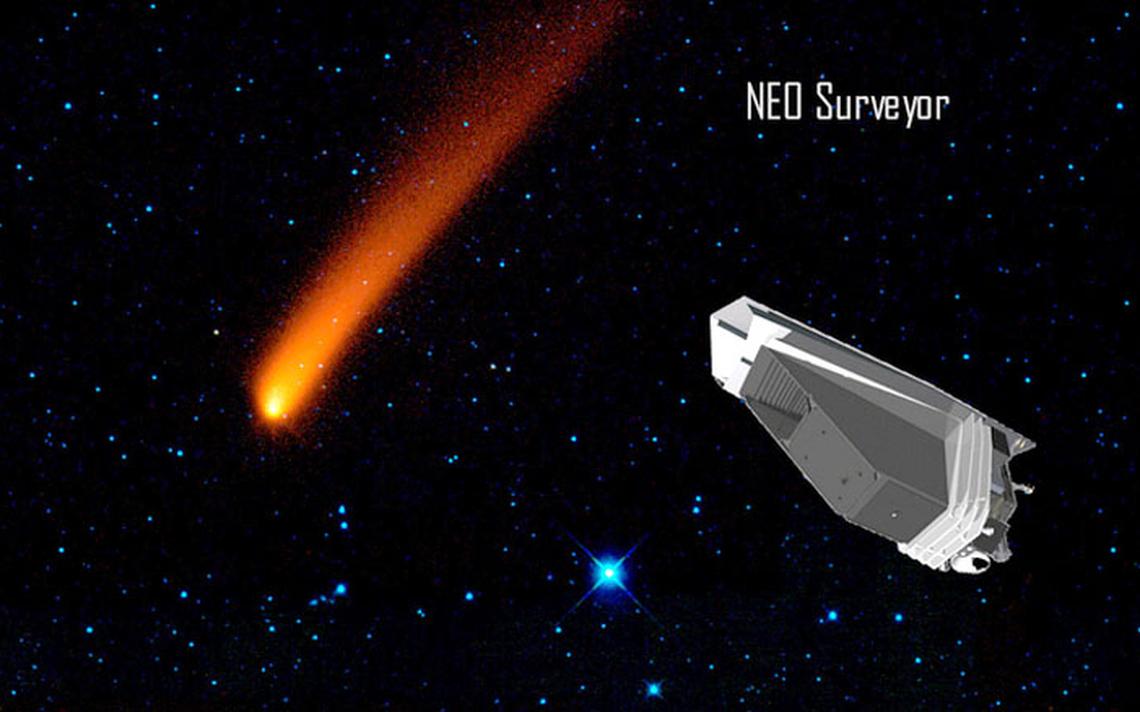

Space.com: Any new words on your proposed NASA Near Earth Object Surveyor spacecraft, a space-based infrared telescope capable of detecting asteroids close to Earth?

Johnson: From a technical standpoint, everybody agrees that this project is ready to move on into phase B, a preliminary design. The uncertainty right now is what the future budget is going to be. Our planetary defense program does not have adequate budget out through the number of years it will take to develop NEO Surveyor as yet.

Space.com: Looking back and eyeing the future, how do you appraise NASA's planetary defense program?

Johnson: The program at NASA continues. Using ground-based capabilities in 2020, it looks like the number of found NEOs is going to hit 2,800 [for the year], a record number for us. Most of those are quite small, much smaller than the 140-meter threshold that we're working toward.

The level of which we're finding the 140-meter and larger asteroids remains pretty stable, at about 500 a year. Our projection of the number of these objects out there is about 25,000, and we've only found a little over one-third of those so far, maybe 38% or so. Our models tell us we've got about 15,000 more to find. At 500 a year, you do the math, that's 30 years that we have to get through with these kind of operations today. We can do it quicker. We know we have the technology to do it faster, and that is what NEO Surveyor is all about.

Leonard David is author of the book "Moon Rush: The New Space Race," which was published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook. This version of the story published on Space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years.