Does the explosion of the delta variant mean we need a new COVID-19 vaccine?

Variant has reduced vaccine efficacy against symptomatic illness and transmission.

The rapid spread of the delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 has put more patients in hospital beds and led to reinstatements of mask mandates in some cities and states. The variant, which is more transmissible than previous variants, also seems more able to cause breakthrough infections in vaccinated people.

Fortunately, vaccines are forming a bulwark against severe disease, hospitalization and death. But with the specter of delta and the potential for new variants to emerge, is it time for booster shots — or even a new COVID vaccine?

For now, public health experts say the far bigger emergency is getting first and second doses into people who haven't had a single shot. Most people don't need boosters to prevent severe illness, and it's not clear when or if they will. But companies are already looking into updating their vaccines for coronavirus mutations, and there is a good chance that third shots are coming soon for some people. Already, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have greenlighted booster shots for immunocompromised individuals.

Related: Coronavirus variants: Here's how the SARS-CoV-2 mutants stack up

"I think we're looking at an inevitable move toward boosters, at least in higher-risk people like those of advanced age and obviously the immunocompromised," said Dr. Eric Topol, a professor of molecular medicine at The Scripps Research Institute in California.

Vaccine developers are working on the question of whether future COVID-19 shots will need to be tweaked for the delta variant, or other new variants. For now though, initial evidence hints that boosters of the original vaccine should add protection against delta.

Vaccine efficacy against delta

While all the COVID-19 vaccines in the U.S. are doing a fabulous job of preventing severe disease and death, it's clear that breakthrough infections are more common with this variant. Data on efficacy is still emerging, and efficacy is a moving target depending on a lot of factors. It's hard to make apples-to-apples comparisons between countries or hospital systems, said Jordi Ochando, an immunologist and cancer biologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Different countries have different levels of vaccination, have used different vaccine mixes with different dose scheduling, and have different populations with different age stratification, comorbidities and levels of previous infection.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, synthesizing data from different countries suggests the mRNA vaccines by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna are probably up to 60% or as low as 50% protective against infection with delta, Topol wrote on Twitter. That's right on the border of efficacy at which the Food and Drug Administration would approve a new COVID-19 vaccine. The J&J vaccine is probably less protective against symptomatic illness than a two-dose mRNA vaccine, based on studies finding that it elicits lower levels of neutralizing antibodies (which block the virus from entering cells).

Data is now emerging that the J&J vaccine likely prevents severe disease from delta as well. Though people with symptomatic breakthrough infections can spread the delta variant, the vaccines do still seem to reduce the likelihood of transmission by making any infection that does occur shorter. A study conducted in Singapore found that viral load started at similar levels in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals who were infected with delta, but it dropped much faster in vaccinated individuals, beginning a steeper decline around day 5 or 6 of illness. This could mean that vaccination shortens the infectious period. However, more confirmation is necessary to show whether the Singapore results will hold up. The discovery that vaccinated people can have viable virus in their noses if infected is what made the CDC reverse its recommendation that vaccinated people did not need to wear masks.

Why delta can break through

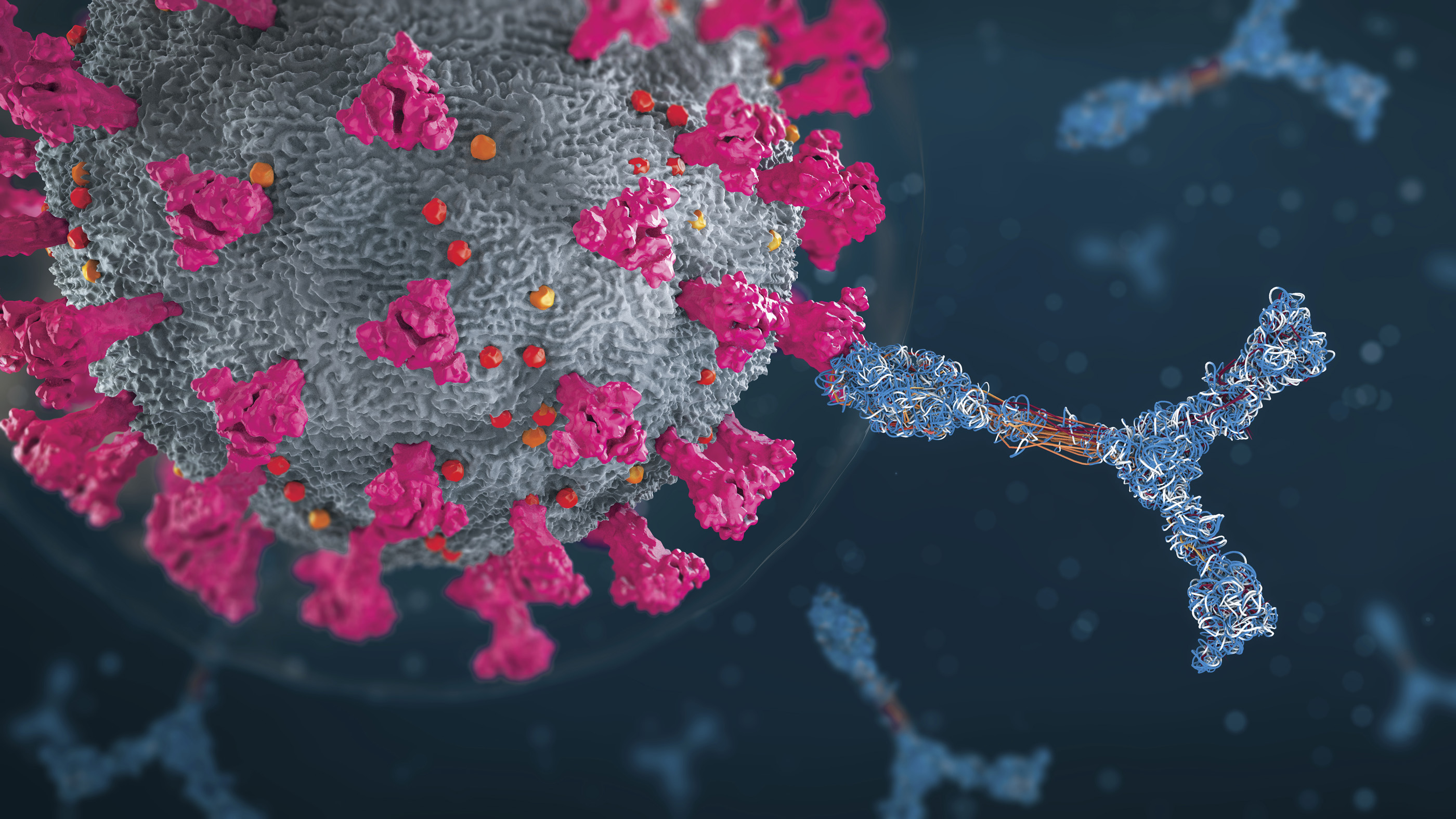

It's not clear exactly why delta can break through vaccine-induced protection more frequently, but there may be multiple factors at play. One is that the antibodies that the vaccine elicits may not bind to the virus variant as well. Delta appears to have spike mutation proteins that make original coronavirus antibodies a worse fit, according to research published in Nature in July. This means that previously infected and vaccinated people have antibodies that aren't quite as protective against delta as they were against the original or alpha variants, said Yiska Weisblum, a postdoctoral researcher in retrovirology at The Rockefeller University in New York.

Another possible reason for waning efficacy is that the immune system starts letting down its guard over time. This happens with the pertussis vaccine, which is why expectant parents and other adults who are going to be around unvaccinated newborns should get booster shots.

"Right now, the U.S. is the driver of the world delta wave, and we are the leading force of nurturing new variants, because it's out of control here."

Eric Topol

Whether waning immunity is likely to be a problem for COVID-19 vaccines is currently a hot topic among researchers. Israeli health authorities say they've seen an increase in breakthrough infections in people immunized in January versus March and are concerned about an uptick in more severe breakthrough cases in those 60 and older, according to Haaretz.

Data from an Israeli HMO published on the preprint server medRxiv before peer review found that 2% of people who requested a PCR test for any reason post-vaccination received a positive result. People vaccinated more than 146 days before being tested were twice as likely to experience a breakthrough infection. The vast majority of the cases in the study were delta. It's difficult to track waning immunity because you need to revisit the same group of people over time, tracking their infection status, Scripps' Topol told Live Science. That kind of data hasn't really emerged yet. But Topol said he's transitioned from skepticism over waning immunity to belief that it is occurring.

"It does look like there is a substantial interaction with delta finding people who are several months out from when they got fully vaccinated," Topol said. "It's a double hit. If you were six months out, and there is no delta, you're probably fine. The problem is this interaction."

Designing next-generation COVID vaccines

Delta's ability to infect the fully vaccinated raises questions about the best strategy going forward. One option would be to give a booster of the same vaccine, raising antibody levels to what scientists hope will be protective levels against delta.

Vaccine manufacturers are also studying versions of the vaccines that update the spike protein targeted by their vaccines.

But trying to play catch-up with delta-specific vaccines might be akin to a game of whack-a-mole, said Dr. Krutika Kuppalli, an infectious disease specialist at the Medical University of South Carolina. There was talk of updating the mRNA vaccines with a spike protein specific to the alpha variant, Kuppalli told Live Science. Now, of course, alpha is vanishing on its own, being replaced by the far more transmissible delta.

"By the time [a new vaccine] might even be ready then we're on to the next one," Kuppalli said.

Related: 14 coronavirus myths busted by science

If delta has taught us anything, it's that ideally, a future SARS-CoV-2 vaccine wouldn't be delta-specific, but rather universal to all potential SARS-CoV lineages, Topol said. A universal vaccine could draw on similarities between the viruses — SARS-1, which emerged in 2003, is genetically 95% similar to SARS-CoV-2, after all — and be reverse-engineered to produce potent antibodies seen in some people infected with SARS viruses, Topol said.

"We could get there soon," Topol said. "That would hopefully be an enduring solution rather than an 'each Greek letter' solution." (Each new coronavirus variant of concern gets a new Greek letter name.)

Another promising notion is that of a needle-free, nasal spray vaccine against COVID-19. Nasal vaccines deliver directly to the spot where the virus lands and elicit immunity right in the mucous membrane that lines the nose. This mucosal immunity can combat the virus quickly, reducing viral replication in the nose, and thus tamping down viral shedding and transmission, University of Alabama at Birmingham researchers wrote July 23 in the journal Science.

A more immediate option might be to harness the advantages of having multiple approved vaccines, said Mount Sinai's Ochando. Mixing and matching vaccines seems to give an immunological boost over boosters of the same time, Ochando told Live Science, citing several papers published in The Lancet.

But even a booster of the original vaccine is likely to help improve immunity against delta. Weisblum and her colleagues have found that people who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 before delta became predominant and then got fully vaccinated have a broader array of antibodies than those who were only infected or those who were only vaccinated. This suggests that when the body sees some version of SARS-CoV-2 three times, it mounts a broader campaign against the invader — strong enough to take down even the delta variant. The researchers even tested these triple-strength antibodies against a spike protein mutated in the lab to resist antibodies from infection or vaccination and found that they conquered this multiple-mutant spike.

"This data suggests that boosting definitely has the potential to increase the breadth of our antibody responses," Weisblum wrote in an email to Live Science. "It also suggests that boosting with the wild type original virus spike could be good enough (since the convalescent vaccinated individuals only saw the original spike), but updating the vaccine to mimic circulating or potentially emerging variants should increase the breadth of the response even more."

An uncertain landscape

One reason the future of COVID-19 vaccines against new variants is hard to understand is that scientists aren't yet sure which immune cells best represent vaccine efficacy in the long term. Most studies now look at neutralizing antibodies. These are a good proxy for protection against infection, said Dr. Zain Chagla, an infectious disease specialist at McMaster University, but may not be as good a representation against protection against severe disease. That's because the immune system recruits a bevy of other cellular protectors such as B cells and T cells to fight once a virus invades. These defenses aren't as quick to the punch as neutralizing antibodies, but they can prevent an infection from turning serious.

Over time, though, antibodies decline (if they didn't, your blood would turn into a sluggish goo of antibodies), while long-term immune cells such as memory B cells and plasma cells persist, ready to mount a new response should the virus reappear again. One challenge for assessing vaccine efficacy going forward will be figuring out which sorts of immune cells to measure to determine how protected someone is from disease after antibody levels decline.

For diseases like hepatitis and measles, researchers have determined a cutoff for an antibody level that provides protection, Chagla said. "As long as you're over that cutoff, it tends to predict success or failure better than just, 'higher is better,'" he said.

There may be a similar cutoff for coronavirus antibodies, but researchers don't know what it is yet.

The trouble with waiting for this data, Ochando said, is that scientists have to study reinfections as they happen. Allowing reinfections opens up the possibility of allowing for more transmission, severe illness and spread. Thus, boosters might be ethically necessary as a precaution, even without rigorous clinical trials delineating their efficacy, Ochando said.

If a third dose of an existing or new formulation of COVID-19 vaccine proves necessary, it doesn't necessarily follow that everyone will need a COVID-19 shot every six months to a year for the rest of their lives. Some vaccines, like the Hepatitis B vaccine, perform best with a 3-dose series, after which there's rarely a need for a booster. It might be that three doses of an mRNA shot at the right spacing will provide strong and long-lasting protection, Céline Gounder, an infectious disease specialist and epidemiologist at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine, said on Twitter.

Whatever the data ultimately shows about the need for boosters, the real bang for the vaccination buck still lies in first shots, not third shots, Kuppalli told Live Science. Facing COVID-19 unvaccinated is much more dangerous than facing it fully vaccinated, and the continued circulation of the virus around the globe just means more opportunity for mutations that could benefit the virus.

"Right now, the U.S. is the driver of the world delta wave, and we are the leading force of nurturing new variants, because it's out of control here," Topol said.

The danger of being unvaccinated is global. Worldwide, only 15.6% of people are fully vaccinated, according to Our World in Data. This has many health experts concerned that high-income countries will be busy handing out booster shots while the rest of the world burns. It's another ethical quandary, Ochando said. Distributing booster shots to the immunocompromised and elderly in wealthy countries makes sense, he told Live Science, but providing third shots to young, healthy people in rich countries is hard to swallow when only 2% of Africa's population has been fully vaccinated, according to the Africa Centres for Disease Control numbers.

Kuppalli agreed.

"I understand countries want to take care of their own, but I think we need leaders to step back and look at the global picture and look at why we are in this continued cycle and look at why these variants keep emerging," Kuppalli told Live Science. "And the reason the variants keep emerging is we are unable to keep the global rate of the virus down."

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.